The top 5 usability testing myths

Rolf Molich debunks some commonly held misconceptions about the efficacy and appropriate application of usability testing.

If you want to find out more about usability testing, there are still a few places left for Bearded's introductory workshop on the topic at Generate New York on 27 April.

Usability testing is by far the most widely used usability evaluation method. Nonetheless, it’s often conducted with poor or unsystematic methodology and so doesn't always live up to its full potential. This article presents five controversial beliefs about usability testing and discusses if they are myths or if there is some useful truth to them. The discussion leads to practical advice on how to conduct better, faster and cheaper usability tests.

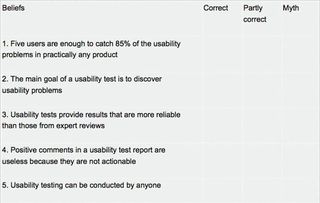

I have listed the beliefs in the table below. Before you read on, I suggest that you pause and deliberate. Please mark your opinion about each of these beliefs. Which are correct, and which are myths?

The Comparative Usability Evaluation (CUE) studies

The results reported in this article are based on Comparative Usability Evaluation studies and the author's experience from conducting quality assurance of professional, commercial usability tests.

In a Comparative Usability Evaluation study, teams of experienced usability professionals independently and simultaneously conduct a usability study using their preferred usability evaluation method (most often usability testing or expert review). Their anonymous test reports are distributed to all participants, compared and discussed at a one-day workshop. Websites that we've tested include Hotmail.com, Avis.com and the website for the Hotel Pennsylvania in New York.

The first CUE study took place in 1998. Until now, nine CUE studies have taken place with more than 120 participating usability professionals. The number of participating teams has grown from four in CUE-1 to 35 in CUE-9.

The key purpose of the CUE studies is to determine whether results of usability tests are reproducible. Another purpose is to cast light on how usability professionals actually carry out user evaluations. After the first studies clearly showed that usability test results are not reproducible, we started to investigate why and what could be done to make results more similar.

More information about the CUE studies is available at DialogDesign.

01. Five users are enough to catch 85% of the usability problems in practically any product

Myth. The CUE studies consistently show that the number of usability problems in most real-world websites is huge. Most CUE studies found more than 200 different usability problems for a single state-of-the-art website. About half of them were rated serious or critical.

Few teams reported more than 50 problems simply because they knew that reporting more than 50 problems is unusable. Many teams tested eight or more users and reported 30 or fewer problems – just a fraction of the actual number of problems.

Even in CUE studies with 15 or more participating teams, about 60 per cent of the problems were uniquely reported. Chances are that if we had deployed 100 or even 1,000 professional teams to test a website, the number of usability problems found would have increased from 200 problems to perhaps 1,000 or more.

So when you conduct a usability evaluation of a non-trivial website or product, most likely you will only find and report the tip of the iceberg – some 30 random problems out of hundreds. Even though you can't find or report all problems, usability testing is still highly useful and worthwhile, as I will explain later in this article.

This myth is hard to defeat, partly because the usability guru Jakob Nielsen kept promoting it until a few years ago. His website still says it, at least indirectly, in the graph:

I agree with Jakob that you only need to test with five users. But the correct reason is that five users are enough to drive a useful iterative cycle. In other words, once you have conducted five test sessions, stop testing and correct the serious problems you have found. Then conduct additional test sessions if time and money permit.

Never claim that testing will reveal all usability problems in a non-trivial product.

02. The main goal of a usability test is to discover usability problems

Myth. The primary reason for conducting usability tests should be to raise awareness among stakeholders, programmers and designers that serious usability problems exist in their own product. Some development teams believe that usability problems only exist in other people's products.

Of course, we also conduct usability tests to discover usability problems so they can be corrected. But usability testing is an expensive way of finding usability problems, so finding problems should not be the only purpose for conducting a usability test.

Use usability tests to motivate your co-workers to take action to prevent usability problems.

03. Usability tests provide results that are more reliable than those from expert reviews

Myth. The CUE-4, 5 and 6 studies compared results from usability tests of a website to results from expert reviews of the same website. The studies clearly showed that there were no significant differences in result quality. Actually, results from expert reviews were slightly better and cheaper to obtain than usability test results.

It's a myth that usability testing is the gold standard against which all other methods should be compared. The CUE studies have shown that usability tests overlook problems, even serious or critical ones, just like all other usability evaluation methods. There are several reasons why usability tests are not perfect. One of them is that they're often conducted with poor or unsystematic methodology. Another one is that the test tasks often do not adequately cover all important user tasks. A third reason is that test participants frequently are not representative.

This CUE result only applies for reviews conducted by true usability experts. It takes many years (some say 10 or more) and hundreds of usability tests to gain the experience and humility necessary to conduct fully valid expert reviews.

In an immature organisation, inconvenient expert review results may be brushed aside by the question, "These problems are your opinion. In my opinion, users would not have any difficulties with this. Why are your opinions better than mine?" Usability tests are much better than expert reviews in convincing skeptical stakeholders about usability problems. It's easy to question opinions. It's hard to observe one representative user after the other fail a task completely without admitting there are serious usability problems.

Expert reviews are valuable, but they are also politically challenging.

04. Positive comments in a usability test report are useless because they are not actionable

Myth. Do you appreciate occasional compliments about your work? Sure you do. That's why usability test reports should contain a balanced list of both positive findings and problems.

Usability test reports most often tell inconvenient truths. Substantial, positive findings serve at least two purposes: they prevent features that users actually like from being removed and they make it easier to accept the problems. Remember: even developers have feelings.

At least 25 per cent of the comments in a usability test report should be positive.

05. Usability testing can be conducted by anyone

Correct. Anyone can sit with a user and ask the user to carry out some tasks on a product. So, in principle, anyone can do usability testing.

But quality usability testing that delivers reliable results is different. Quality usability testing requires skills like empathy and curiosity. It requires profound knowledge of recruiting, creating good test tasks, moderating test sessions, coming up with great recommendations for solving usability problems, communicating test results well, and more. The CUE studies have shown that not every usability professional masters these skills.

We need to focus more on quality in usability testing.

Better, faster, cheaper!

Project managers tell me that, just like everyone else, usability evaluators need to improve their efficiency. My suggestions are:

1. Better

Today, a usability test should be considered an industrial process. Gone are the days when a usability test was a work of art and beyond criticism. Industrial processes are controlled by strict rules that are written down, reviewed and observed.

Strict rules enable quality assessment of our work. As responsible professionals we should welcome this.

2. Faster

Test with between four and six test participants. More test participants are a waste of time since it's an elusive goal to find 'all' problems – or even all critical problems.

Focus on essential results. Write short reports that can be released quickly, ideally within 24 hours after the final test session.

3. Cheaper

You can't control what you don't measure. Measure cost and productivity of your usability tests. Keep a timesheet so you always know exactly how much a usability test cost your company. Compare your productivity and quality with your peers.

It's hardly ever cost-justified to have two or more specialists working on a usability test. You could argue that a usability specialist may overlook important problems that a co-worker would notice, but the CUE studies show that, even if you deploy 10 experienced usability specialists, important problems will be overlooked.

Consider carefully whether an expensive usability lab is cost justified when two ordinary meeting rooms with inexpensive TV equipment will make it possible to observe usability tests equally well.

Consider remote or even unattended usability testing to reduce costs. Recent CUE studies indicate that these methods work almost as well as traditional usability testing.

Prevention is better than cure

My personal experience is that about half of the problems I find from usability testing are violations of simple usability heuristics that we've known for more than 20 years such as 'Speak the users' language', 'Provide feedback' and 'Write constructive and comprehensible error messages'.

Usability tests are expensive. They are an inefficient way of discovering usability problems. Many of the problems uncovered by a usability test should never have occurred in the first place – they should've been prevented by the designers' or programmers' knowledge of basic usability rules.

The main lesson from myth two is: use usability tests to motivate your co-workers to take action to prevent usability problems. In other words, consider designers and programmers as the primary users of your usability test results. Let's use usability testing to motivate our primary users to learn about common usability pitfalls. Let's focus on preventing problems rather than curing them.

This article was first published on 27 Feb 2013. Main image used courtesy of Smart Chicago Collaborative via Flickr under the Creative Commons License.

There are still a few places left for Bearded's Introduction to Usability Testing at Generate New York on 27 April. If you buy a combined workshop and conference pass, you will save $125! Get your ticket now!

Thank you for reading 5 articles this month* Join now for unlimited access

Enjoy your first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

*Read 5 free articles per month without a subscription

Join now for unlimited access

Try first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

Get the Creative Bloq Newsletter

Daily design news, reviews, how-tos and more, as picked by the editors.