'There was a creative void that we both wanted to fill': a day in the life of designers Benji Wiedemann and Alex Lampe

Wiedemann Lampe founders discuss the dynamic of their creative partnership and approaching design briefs with forensic accuracy.

Benji Wiedemann and Alex Lampe founded their brand consultancy as an intersection between culture and commerce. Launched in 2016, Wiedemann Lampe embrace a simple mission – building brands through strategic excellence. The pair choreograph the agency with an artistry that extends beyond the realms of comfort to deliver inter-platform brand management and multi-audience engagement.

With Benji's design expertise and Alex's technological knowledge, Wiedemann Lampe was born from a decade's worth of observing, educating and innovating, building an agency that connects audiences through evocative, immersive experiences. As part of our Day in the Life series, I caught up with Benji and Alex to discuss their creative partnership, inclusivity in the industry and the forensic practice of tackling design briefs.

Tell me about a typical day in your role

Benji Wiedemann: The commute is a really important part of the day for the both of us. It allows us to separate life at work from life with our families, giving us the space to decompress, reset, or prepare mentally for our meetings and priorities for the day.

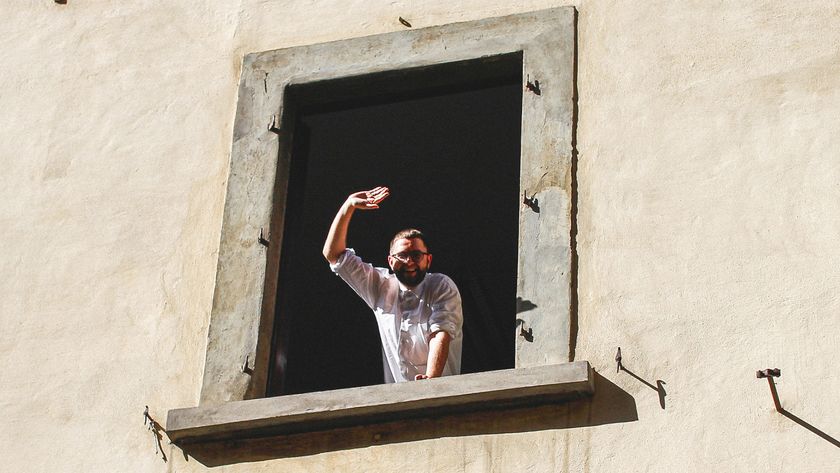

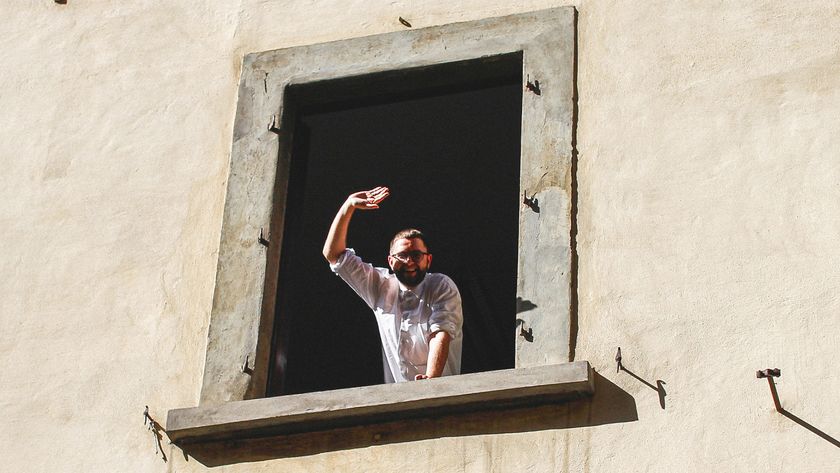

We both walk, me from Lower Clapham and Alex from London Bridge, to our studio near Spitalfields. Alex is a bit of a street photographer, so often takes pictures on the way – he’s great at looking for stories in the mundanity of the commute.

Once we reach the studio, our days are punctuated by time zones. It can start by running a remote workshop with the Middle East, then presenting to clients in the UK and Europe, before heading over the pond to speak to New York in the afternoon. Our West Coast clients will often close out the day, with calls around 6 pm.

What was your early career like?

Alex Lampe: We were both very lucky to start working as designers at Lewis Moberly back in the early 2000s as our first jobs out of university. It’s there where we met.

BW: With a digital vocabulary that was very rare for the time, Alex was the golden boy of the agency. I like to compare it to a Cinderella situation – Alex was attending the balls, getting invited to client meetings and the trips to Paris, while I was stuck sweeping the floor of the castle.

AL: We were able to learn so much about the industry first-hand, and it was a privilege to work under the well-respected creative forces of Mary Lewis and Robert Moberly at such an early point in our careers. For all it gave us, and the endless lessons we learned, we eventually felt that we wanted to explore different projects, or different facets of those projects. There was a slight creative void that we both wanted to fill.

If I’m being honest, I couldn’t quite work Benji out at first – we are pretty different characters. But we soon became friends, during our time at Lewis Moberly. Benji always had the vision to start an agency of his own, but I never had the appetite to spearhead an agency and take on the overheads and complications of leading large teams. Eventually, I realised that with our shared mindset, my digital approach and Benji’s charisma and creativity, we may have something special - so I slowly warmed to the idea.

Next thing we knew, we were sat on our hired desks in Farringdon, with three clients we had wrangled from friends-of-friends, thinking “now what?”. And that’s when Wiedemann Lampe was born.

What’s it like working together as friends and business partners? Do you find yourselves talking about work when you see each other socially?

BW: I’ve been brewing elderflower champagne recently, and I think that makes a nice analogy for our relationship. Our work together is the alcohol, the good stuff, the heavy hitting stuff, while the bubbles, the fizzy stuff, are a bonus – just like our friendship.

We balance each other out well. I have a tendency to be overly critical, and that can end up being destructive. Alex is the more objective voice in my ear telling me to shut up and get on with stuff.

AL: We’re both parents now, so while it’s harder for us to go for the weekend drinks we used to, we do sometimes get chances to spend time together outside of work – although this mostly happens when we’re away travelling. While we try not to speak about the day-to-day outside of the studio, we find that a hotel bar after a busy day of client meetings is a great place to reflect on the journey we’ve been on together, and discuss the strategic direction of the business.

How do your approaches to creative director differ?

AL: I tend to work in a much more hands on way, my process is very iterative. I work across the whole project, from the initial strategy to the final digital expression and coding.

The majority of our projects are very complex and multi-dimensional, which means I need to be constantly rethinking and improving what we’re doing to get to our end goal.

BW: I’m sure people think I’m just dilly-dallying, as I spend a lot of my time hopping from project to project and person to person. As someone who’s neurodivergent, I need to move a lot to be able to concentrate. Unlike Alex, I can’t focus while sitting in one place.

Only in this state am I am able to process hugely complex problems and bring them to a one focused ‘singularity’. From this point I can start constructing the whole project structure. These are normally big strategic moves that bring clarity and drive everything we do towards that one goal.

What’s your approach to pitching?

BW: We’re very lucky in the fact that our work is all inbound at this stage, so we very rarely find ourselves pitching for projects.

Most of our work starts as RFPs for projects that are deeply complex organisational challenges, so jumping straight into creative solutions wouldn’t make much sense. Our process involves defining the brief and the organisation’s intent before even thinking about the creative or design output.

We’ve found that, if you don’t do the groundwork beforehand and drive a project based on primary research, you run the risk of building creative work on flimsy (and often false or irrelevant) insights.

Instead, we tackle the brief more forensically by identifying the organisational challenges and opportunities at play. From this point we start to articulate the strategic approach, from organisational purpose and culture; internal processes and structures; visual and verbal identity to service design blueprints and audience experiences.

Where do you start when working with a well-known and loved institution such as the Louvre?

AL: We need to first understand that the Louvre has three locations - Paris, Lens and Abu Dhabi. The Louvre Abu Dhabi is based on an intergovernmental agreement between France and the UAE, making it vastly complex. Many different currents come into play, so you need to understand the equity and relation of all components forming the organisation.

We always want to go wide before we go deep, understanding the organisation from multiple dimensions. We’ll conduct interviews and workshops to pinpoint where the tensions are, the personality of the organisation and the people within it – warts and all.

With institutions of this size, it’s possible for different teams to essentially be different organisations. It’s our job to get a full vision through all of these intricacies, and piece together the cohesive story by detecting patterns and discrepancies.

As client partners we have two ears and one mouth. Listening on every level and stage of the project is crucial.

How can cultural institutions use design to help them stay relevant?

BW: It’s important to remember that design touches and should inform every aspect of an organisation. Every important component should not be there by chance, but because of a conscious choice. The visual articulation of a brand is usually the final step in this process for us.

Design should encompass organisational culture and decision-making frameworks, the construction of internal processes, mapping the future to allow an institution to stay relevant and flexible across external and internal service elements.

The design process should be used to define cultural responsibilities and footprints. It can help it reach audiences it doesn’t yet, do things it was unable to before, and be ahead of its peers.

What project are you most proud of and why?

BW: As we are a very compact team, each project we take on must be an opportunity for us to grow, both individually and as an agency.

With these criteria in mind, the repositioning of the Louvre in Abu Dhabi gifted us with the greatest learning curve. The project was transformative for us as a business. Tackling such a vast brand with so many moving parts, all while learning about the several cultural backdrops and its nuanced cultural space, taught us and the team so much.

That project marked a shift in how we approach projects at Wiedemann Lampe. It has helped us re-think our approach and processes, redefine our vocabulary, and show us the impact our work can have. The Louvre had given us their full support and trust in the process and we’ll always be grateful for that.

Tell me about a tricky work-related challenge and how you approached it

AL: We’ve had projects in the past with massive scopes of work with deadlines that definitely didn’t reflect that scope. Think two years’ worth of work, to be completed in three months.

Those projects can be brutal for a team of our size, but once a client commits to us – we commit to them, and we don’t let anything stop us from delivering on our promise. In those cases, we know to be heavy on the thinking. The more we think everything through, making sure the ideas are robust and precise from the beginning, the less time we waste in the execution stage of the project.

How inclusive is the design industry in 2024?

AL: It’s a systemic issue. We’re always looking to have a diverse team as inclusivity is baked into the cultural sector and the projects we execute within it, but the CVs we receive are not always reflective of that.

I do think the problem goes beyond the design industry itself, into schools and universities, with creative education not being easily accessible for a lot of people. It’s still a privileged industry to be in, and we hope to see that change.

BW: To build on this, as two white, middle-class men, we’re aware of the privileged positions we have been given – so we think it’s important for people within those underrepresented communities to have their voices heard in the industry. We’re cautious of taking up spaces in conversations around diversity and inclusion that should be reserved for those with the lived experiences to inform them.

What career advice would you give your younger selves?

AL: I don’t regret doing it when we did – but my advice to younger people is to not rush to start your own company. It’s an amazing experience, but you do need to have the experience behind you to help inform that journey.

We did it with one job in the bank. It’s liberating, but a lot of pressure – you have the weight of clients, a team, and your own livelihoods on your shoulders. Those initial experiences are crucial – so get as many as you can.

BW: The advice I wish I could’ve given to myself would have been: be kind to yourself, and trust yourself, we’re all works in progress.

Discover more about Wiedemann Lampe

Get the Creative Bloq Newsletter

Daily design news, reviews, how-tos and more, as picked by the editors.

Thank you for reading 5 articles this month* Join now for unlimited access

Enjoy your first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

*Read 5 free articles per month without a subscription

Join now for unlimited access

Try first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

Natalie is Creative Bloq's staff writer. With an eye for trending topics and a passion for internet culture, she brings you the latest in art and design news. A recent English Literature graduate, Natalie enjoys covering the lighter side of the news and brings a fresh and fun take to her articles. Outside of work (if she’s not glued to her phone), she loves all things music and enjoys singing sweet folky tunes.