A simple introduction to web accessibility

Accessibility can often seem daunting and complex but in fact there are only four types of disability you need to be aware of. Through groupings, simulations and quick fixes, UX and accessibility consultant Ian Hamilton shows that the basics are actually surprisingly simple

1/5 of the population has a disability. That’s a lot of people that we could be potentially failing to reach.

Accessibility is catering for your whole audience, including those with disabilities. Disabilities are when someone’s medical condition comes up against barriers that get in the way of them being able to fully participate (social model of disability) – for example, a flight of stairs to get into a bar, a discriminating comment, food on a high shelf in a supermarket, or an unusable web form.

As designers, developers and copywriters we’re often responsible for causing disability, by creating these barriers. But we also have the power to avoid them or remove them, not just gaining traffic but also improving people’s lives in the process.

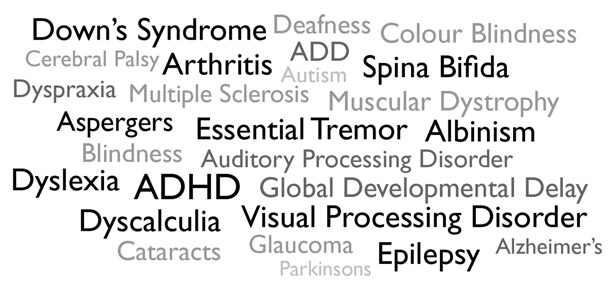

Accessibility is about reaching as much of your target audience as possible. To do that the first step is to understand who that audience is and what their needs are. The disabled audience is sometimes thought of as being something like this:

But that’s actually not it at all. Rather than a sea of medical conditions, luckily it’s pretty simple.

There are only four types of disability that relate to web access: visual, hearing, motor and cognitive.

Many fixes for these groups are both simple and free.

While this article isn’t an exhaustive guide to accessibility (there’ll be suggestions at the end of where and how to learn more), there’ll be an overview of each of these four areas, with a few examples of the kind of adaptations that can make a valuable difference to each group.

Visual

Associated medical conditions include myopia, colour blindness, glaucoma and albinism

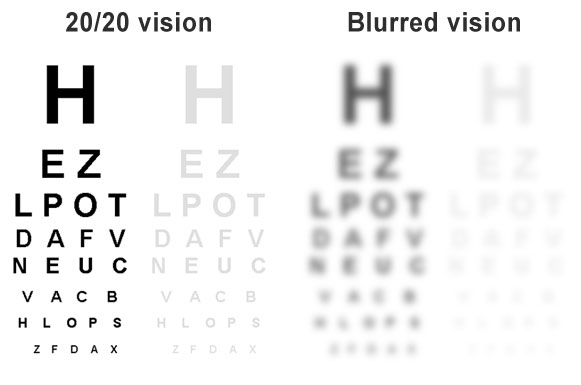

Catering for visual impairments means not relying on subtle visual cues, or even not relying on visuals at all. The simplest way is through size and contrast:

You can easily see the difference that good contrast between foreground and background makes, especially at lower sizes. Snook.ca has a nice contrast checker to help with this. Also make your links as easy to see as possible – bold with a significant difference in colour, ideally also underlined.

There are many types of vision loss, such as patchy, warped or tunnel vision, but not relying on things that are small or low contrast will be useful for most of them.

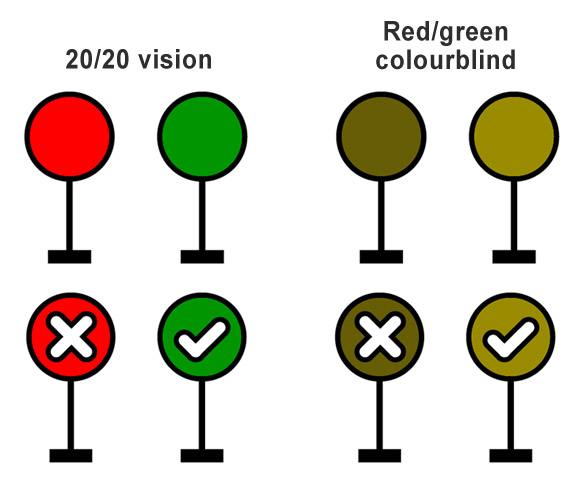

Another type of impairment is colour blindness. The most common is red/green (affecting eight per cent of males) but there are other types too, so avoid relying on colour to convey information.

This example is from a game. The progress markers changed from red to green when you passed them. The issue wasn’t the use of colour, it was the reliance on it. Adding a symbol avoided the issue, and also made it clearer for everyone:

This is extremely common in web forms – ‘correct the fields marked in red’.

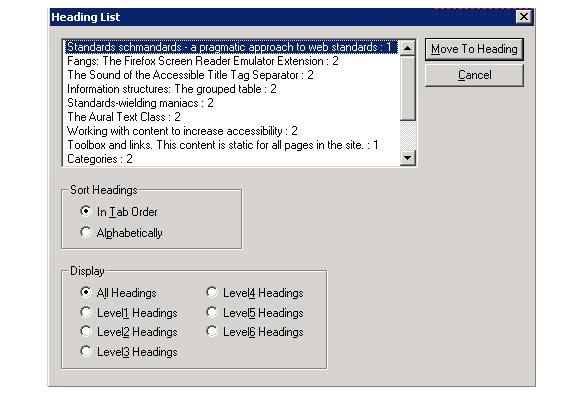

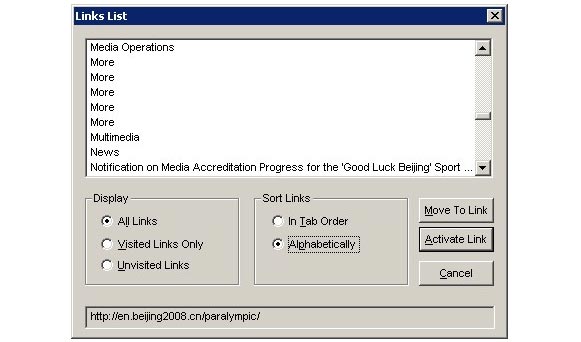

There’s also screenreader software, used by people with severe visual impairments or blindness to quite simply read the contents of the screen out as audio instead. Screenreader users browse in the same way as anyone else does, skimming through titles and links to find items of interest. For example:

For this to work, all headings (properly nested H1, H2 and H3) must be tagged properly, and your links must make sense out of context. If not, you end up with something like this:

Get the Creative Bloq Newsletter

Daily design news, reviews, how-tos and more, as picked by the editors.

So, avoid generic links such as ‘click here’ and ‘more’. Instead, make the text of the link describe the destination. This will also help your SEO.

Also avoid autoplaying audio/video at all costs: it clashes with screenreaders’ speech, rendering the site unusable. There are some big players who do it but it’s a serious issue, Disney is currently in court over autoplaying video. Also, don’t forget your alt tags, and make them concise but accurate descriptions of what your images look like. For instance, if someone reads the alt tag without seeing the image, they should be able to have a fair stab at drawing it. Again, this will also help your SEO.

Hearing

Associated medical conditions include presbycusis, acoustic trauma, auditory processing disorder, and otosclerosis

As the web is mostly a visual medium, people with hearing impairments are generally well served. Sound isn’t usually relied on to get information across, with a couple of exceptions – the main one being video.

All video should ideally be captioned. Captions should include important background sounds (eg a door slamming) and need cutting down so that they can be read as fast as the words are being spoken (speech is up to 150wpm, reading speeds are up to 120wpm). Captions also require a technical implementation in the video player. Because of these issues, captioning can sometimes be too difficult/expensive for small companies/budgets.

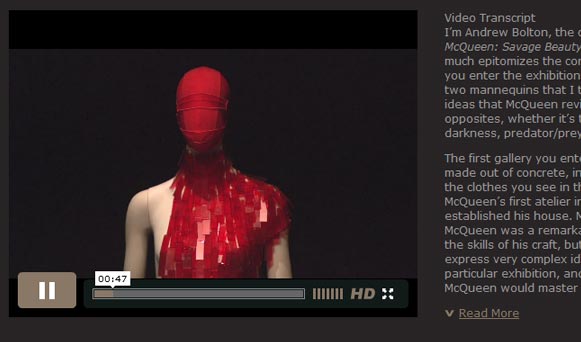

If full captioning is outside your budget, then there’s a cheaper fallback that, while not providing an equivalent experience, still allows access to the information – a transcript. This is a simple HTML version of the information contained in the video. For example, this Alexander McQueen video and transcript:

By comparison, mute your volume then try to make sense of this Sky news video:

Transcripts are easy to do (either by typing, or using a cheap transcription service) and have many benefits, not just catering for hearing impairments but also people without sound (eg in an office or on a mobile browser), and for SEO, quoting, skimming through, in-page browser search etc.

Motor

Associated medical conditions include RSI, cerebral palsy, Parkinson's, and muscular dystrophy

People with motor impairments find using a traditional mouse and keyboard difficult, or even sometimes impossible and use a range of assistive technologies instead, like these button switches:

Input devices have a wide range of complexity, starting from the very simple cause and effect of pressing a single key or button, through the spatial metaphor (hit the furthest key from you to move up) of arrow keys, all the way up to the fine analogue movements needed to use a mouse, keeping precise control over both speed and direction simultaneously.

Thankfully though browsers (and Flash too, but unfortunately not Canvas yet) support simple keyboard access out of the box. Tab to cycle between selectable things, and enter to select them. So be sure not to break this, and also check that your tab sequence is in a logical order.

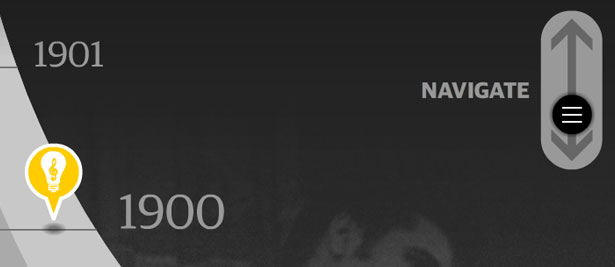

To avoid problems for people who are able to use a mouse or touchscreen but find it difficult, don’t make clickable elements too small or close together, and don’t rely solely on complex movements or gestures such as drag and drop or swiping. Up/down buttons as well as click/drag would have made this Guardian music history timeline usable by many more people:

Lastly, if you want something to be clickable then keep it stationary, or you’re literally asking people to hit a moving target, as in this Marc Ecko example:

If you’re stuck with a moving interface though, there’s a quick workaround – include an obvious pause button to freeze the movement. Alternatively, as Marc Ecko has done, include a separate static version of the navigation.

Cognitive

Associated medical conditions include Down’s syndrome, autism, global developmental delay and dyslexia

Cognitive impairment means not being able to process information as easily. The most obvious fix is to simplify the information, keep it to the minimum needed to get the point across, and avoid unnecessarily complex language jargon or acronyms, as the copy on the Facebook and Blogger homepages both succeed in doing –

This is straightforward to do and standard good practice for writing for the web in general, but also fantastically helpful for the huge percentage of the population who have a significant reading difficulty (including over one million UK adults who have a reading age of below five years old).

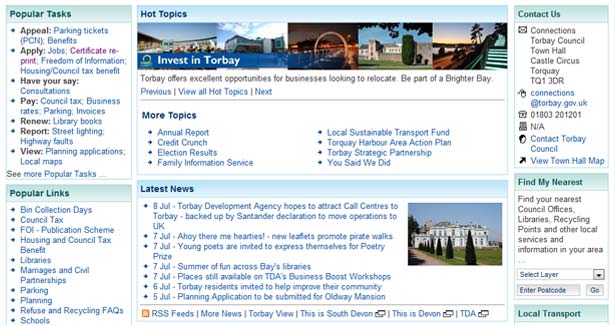

Another powerful tool is simplicity of interface, avoiding situations like this Torbay Council site where people are overwhelmed with too many options, and there is no proper hierarchy:

Also ensure that navigational elements are kept consistent. Often people will navigate via clicking in a familiar position rather than reading all of the text on each menu item.

Use of a clear easy to read typeface is another obvious way to help.

Lastly, animation or movement.

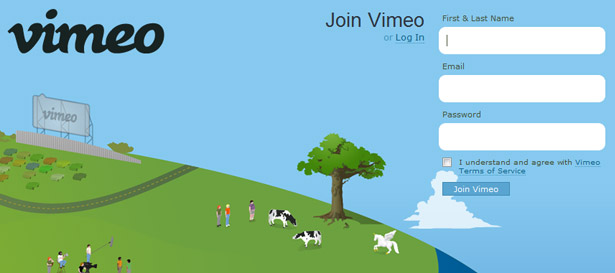

It’s not easy to keep your eye on the text with all that animation next to it. This may seem extreme, but for some conditions (such as ADD or Asperger's) the distracting effect of movement is amplified. So this example can be exactly how even moderate movement feels – very obtrusive. So something as simple as a cloud slowly drifting behind Vimeo's sign-up form...

... can be very distracting, making it difficult to concentrate on the interactive elements.

Also unannounced movement (especially autoplaying video) can go beyond making access difficult, and cause actual distress for people who aren’t able to cope with sudden unexpected change, due to conditions such as autistic spectrum. So use movement and animation sparingly, only when there’s a real need. If you do use it then make it move as the result of a user action instead of moving automatically, and avoid things that animate continuously, ie. just use a quick transition in or mouseover effect instead of something that loops forever.

If there’s no way out of it and you must have autoplaying animation, then as with moving interfaces, be sure to include an obvious pause button.

What next?

Although not an exhaustive list by any means, these examples should at least give you a flavour of who accessibility benefits, the kind of barriers they come up against, and some practical quick and easy tips for avoiding them.

Spending time with disabled people is by far the best way to learn more. If you are able to carry out audience research and user testing then include disabled participants, recruiters don’t charge any more to find them than anyone else.

If not, most people know someone who is disabled (elderly relatives are a good bet, they often have a variety of minor-medium impairments). Sit at a computer with them and chat through what they find difficult and what they’d like to see improved or provided. Whatever your level of audience insight, it will always be just that, insightful.

There are also excellent web accessibility standards (WC3 WCAG2.0) and reams of expertise on design, code, copy and content techniques, but really it all just comes down to this:

Keep these four groups (people who who find it difficult to see, hear, control or process information) in your head from the outset of a project, and you will make a real difference.

Thank you for reading 5 articles this month* Join now for unlimited access

Enjoy your first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

*Read 5 free articles per month without a subscription

Join now for unlimited access

Try first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

The Creative Bloq team is made up of a group of design fans, and has changed and evolved since Creative Bloq began back in 2012. The current website team consists of eight full-time members of staff: Editor Georgia Coggan, Deputy Editor Rosie Hilder, Ecommerce Editor Beren Neale, Senior News Editor Daniel Piper, Editor, Digital Art and 3D Ian Dean, Tech Reviews Editor Erlingur Einarsson, Ecommerce Writer Beth Nicholls and Staff Writer Natalie Fear, as well as a roster of freelancers from around the world. The ImagineFX magazine team also pitch in, ensuring that content from leading digital art publication ImagineFX is represented on Creative Bloq.