Oliver Reichenstein on typography, Japan and hairdressing

Designer, speaker and philosopher Oliver Reichenstein talks to Martin Cooper about design, communication and how Japan changed his life.

This isn't easy. Having spent nearly 90 minutes talking to Oliver Reichenstein, I can't tell you too much about the greying, smiley, fascinating and boldly bespectacled man that sits before me. I can tell you a lot about what leads to making him the man he is but, as for the man in that moment, I know only a few immutable facts.

Firstly, he doesn't trust hairdressers. He cuts his own hair. Next, he doesn't have a business card and steadfastly refuses to be corralled into a job title. Eventually - after some chasing - he concedes he's the founder of Information Architects Inc (iA). "That's not a secret," he says. Netting this fact feels like a victory.

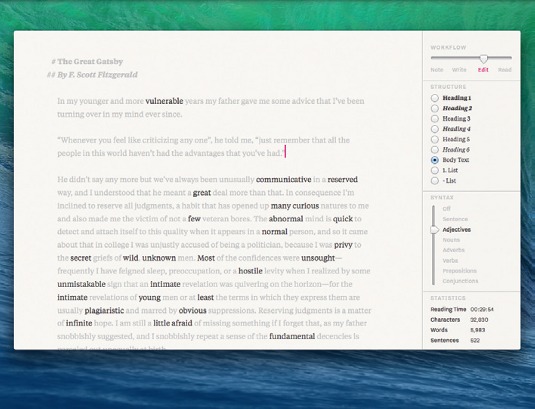

iA is a creative agency with offices in Zurich - Reichenstein's base - and Tokyo. The firm counts Holtzbrinck Publishing, Open Systems AG and the World Intellectual Property Organization as clients. Reichenstein's company also makes the iA Writer text editor app, the writing tool that's sold over one million copies.

The rest of Reichenstein's here and now is, by design, hard to pin down. Not because he's aloof, deliberately evasive or because he is trying to appear enigmatic. Rather, because he's a man fascinated by - and rather mistrustful of - perception.

"The sneakiest question in any interview is: who are you? You always look silly if you define yourself," he says. "It seems that I'm somebody who has some success writing and talking about design, though I don't think I'm an exceptional designer."

Beyond iA, Reichenstein's profile in the industry has been elevated by a speaking career. He gave the opening keynote address at net's Generate conference in London last September. There he spoke darkly about digital entropy. Likening the detritus on the internet to the rising mess of pollution in the seas was the talk's central tenet. The main problem is the inflation of noise, half truths and, to use one his most precisely deployed words, bullshit. It's polluting the web, it's polluting our minds.

Looking back

So, where did his web career start? "If you look backwards, everything makes perfect sense. But maybe it's more constructed," he observes. "I grew up in house full of hairdressers. In my family we have about twenty hairdressers. My grandfather, both my parents and so on. Hairdressers consider themselves artists. Hairdressers are designers, not artists. Design has a function. A talented hairdresser tries to find out who you are, tries to make you look as good as you can. You can do wonders and you can perform substantial design. The shape of your head, the type of hair and how well you handle your scissors play an important role, but what discerns an average from an excellent hairdresser is not the technique, it is the talent to understand who their client is. That applies to all forms of design." Unfortunately, he tells us, there are very few good hairdressers, so he sticks to trimming his own locks.

Who is Reichenstein?

For a man so reluctant to discuss today's Oliver Reichenstein, he continues to recount his youth with undeniable joy. "My grandfather was an artist. A painter. I got oil painting lessons before I could write. I grew up with that romantic background. I then went to school and studied philosophy." After studying philosophy, he had to find a way to make money. Reichenstein's room mate worked at an internet agency. Continuing his story, he remembers: "We were online all the time. Making things, creating websites. But, being able to continue making these things professionally was something that seemed too good to be true. At the end of the nineties, at least. You'll pay me for being online? Seriously?"

Computers, he tells us, entered his life very early. As a child he owned a Dragon 32, at a time when the Commodore 64 reigned supreme. "At first, I leaned BASIC. One of the first things I programmed was a text editor. I figured if I made a smaller pixel typeface, it would help me write. When I made Writer I had completely forgotten about that. That logical connection between my first programming and my current passion may be a searched link. I remember that I could make the uppercase letters work, but I'm not sure how far I got with the lower case letters. We walk in circles."

As a graduate with bills to pay, he started as a copywriter for a small internet startup. He found the experience fun but soon he felt the limits within the local agency.

"Somehow," he concludes, "I managed to make a profession of what I like most, which is designing. I was very shy for a long time about calling myself a designer because I never went to art school."

Attending art school was an option. His grandfather told him to train his brain with philosophy and, if art is something you're drawn to, you'll return to it naturally.

"After my studies, I have never touched a canvas any more. Designers and artists really have different mindsets. Having a canvas in front of me, is terrifying. I have nothing to say as an artist."

The making of a man

After working for a small agency he tried life in a much bigger branding company. He worked there for four years, focusing on clients like Deutsche Telekom and Bild.

"After four years there I was tired," he tells us. "The salary was unbelievable and that salary allowed me to take some time off and go to Japan on holiday."

The holiday marked the start of a love affair with the country and he took the bold decision to move there. "I studied Japanese. I thought, well, I'm 33 now, this may be the last chance to make a major change in my life and so I took it. Maybe half a year after arriving in Japan I met my wife."

Recounting his first few days as a nowhere man in a nowhere land, he says: "What was interesting, after working in communication for four years, [Japan] was completely silent. Tokyo is a loud city. Japan is a loud country. It's not at all zen, bells and bamboo. It's extremely loud, but if you don't understand what's being said or written you can relax in a way you can't at home. Suddenly, you're not bombarded with all kinds of sale propositions anymore."

With some formal education, guesswork and happenchance, he began to pick up the language. "As an interface designer, it's beyond interesting, " he tells us. "You see things as a little kid. You don't understand how things work. You just have to observe and ask what could this be? What does it do? Is it dangerous? What happens if I touch it? The most trivial things like ordering soup become a challenging task."

Summing up his early days in Japan, Reichenstein says, "Ultimately, coming from a verbally-loaded environment - philosophy, brand design, information architecture - it was purifying to forget words and to see all the other ways humans communicate.

"When you can't read, you start looking at the shape of writing. When you know the basic elements of kanji, rope, boat, man, tree, mountain, fire, water, you can start guessing at whether this is sign is symbolising something good or bad, soft or hard, easy or complicated, hot or cold. And with distance, I started to appreciate the beauty of Latin typography. Suddenly, I realised this is what's missing on the web. It's a typographic mess. There is no typographic care."

A new passion

Determined, Reichensten started learning about traditional European typography and began translating it into screen typography. "Type design is a drug. I tried it once and since then it never let me go. It gives me great pleasure and it yet makes me feel small, because I am still so bad at it. Once you've discovered the beauty of looking at letters from really close, and you start seeing the logic between the letters, the logic of different components and how they play together it's completely mind-changing."

We discuss Reichenstein's attitude to digital life in general. Specifically the clutter of email, photographs and MP3s. "It's as much of a burden as collecting physical things. When I moved to Japan, I sold everything I had except for books and CDs. The less I owned, the lighter, freer I felt. Now, every time I throw away a computer I feel lighter! Letting go is liberating."

Changed as a designer, materially unencumbered and imbued with a love of typography, Reichenstein moved back to Zurich, motivated, in equal parts, by the terrible earthquakes of 2011 and his growing European business.

Work philosophy

We move on to discuss his blog post Logo, Bullshit & Co., Inc, written in reaction to Marissa Mayer's Yahoo logo redesign in a weekend project. "My message there is simple: brand design is based on brand management. And design is structural work. It's design as a process that defines the shape. It doesn't matter whether you like or dislike a particular colour or shape. That's not what branding is about, or what design is about. It's not even what beauty is about."

Brand design, he asserts, follows a solid brand architecture. Returning to Yahoo, he says, "The problem is most of Yahoo's products are unstructured, lots of them are average or crap. Nobody knows what kind of products it stands for. It's just piling stuff up and adding more expensive stuff to the pile."

So, organisations that think clearly can design clearly. But how can a designer design sensibly when they're not receiving clear and solid information? "If you don't have a clear briefing with a good foundation, and they don't let you get to the bottom of what you need to design, then you should say 'no'. That is, if you can," he says, wringing his hands.

"In practice, of course, the people who need this advice most, can afford it least. They have to take the next project and find their ways around it. It's like a bad relationship. Once things sour, it keeps on getting worse."

Unsurprisingly, Reichenstein is acutely aware of his own position in the industry. He's now successful enough to say 'no'. "Ultimately you need to have a lot of knowledge of people. You need soft skills. You can't just say 'No, fuck off, ass hat!' That's not how business works." He smiles.

We ask what the future holds for Oliver Reichenstein and iA? He tells us, 'Writer Pro' is being finalised and should be out any day now and his firm is hired increasingly to help firms improve internal communication processes. "The information streams inside big corporations are a mess. They look like the Tower Of Babel. We're still happy to design websites but we're drawn into this by our clients more and more." And with that, he nods goodbye.

Words: Martin Cooper Photography: Will Ireland

This article originally appeared in net magazine issue 250.

Oliver spoke at Generate 2013, you can watch his talk here:

Generate is returning to London and New York in 2014, with an outstanding speaker line-up. More information here.

Liked this? Read these!

- Our favourite web fonts - and they don't cost a penny

- The designer's guide to working from home

- How to build an app: try these great tutorials

Thank you for reading 5 articles this month* Join now for unlimited access

Enjoy your first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

*Read 5 free articles per month without a subscription

Join now for unlimited access

Try first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

Get the Creative Bloq Newsletter

Daily design news, reviews, how-tos and more, as picked by the editors.

The Creative Bloq team is made up of a group of design fans, and has changed and evolved since Creative Bloq began back in 2012. The current website team consists of eight full-time members of staff: Editor Georgia Coggan, Deputy Editor Rosie Hilder, Ecommerce Editor Beren Neale, Senior News Editor Daniel Piper, Editor, Digital Art and 3D Ian Dean, Tech Reviews Editor Erlingur Einarsson, Ecommerce Writer Beth Nicholls and Staff Writer Natalie Fear, as well as a roster of freelancers from around the world. The ImagineFX magazine team also pitch in, ensuring that content from leading digital art publication ImagineFX is represented on Creative Bloq.