The making of Transformers

They’re 30-foot-high shapeshifters. They’re made out of thousands of moving parts. And they’re out to beat the living cogs out of one another. Transformers might have posed something of a problem for an average VFX studio. Fortunately, ILM is anything but average...

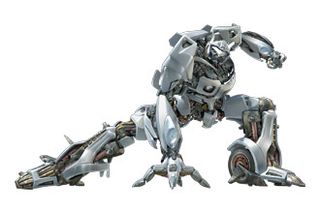

IN FOCUS: Megatron and Optimus Prime disassembled

Here are some fun facts about the Decepticons and Autobots. First we take a look at Megatron vs Optimus Prime, and later we offer some eye-opening statistics on Bumblebee and other key Transformers.

MEGATRON

During most of the film, Megatron is a 35-foot-tall killing machine made from 433,949 polygons and 2,411 pieces of geometry. A second Megatron, however, is 40 feet tall. The most complex Decepticon is Blackout, the helicopter. He has 7,742 pieces of geometry and 1,426,781 polygons. By contrast, the tiny, frenzied, ever-present Soundbyte, which transforms from a radio, has only 871 pieces of geometry and 233,178 polygons.

Character riggers gave animators control systems for creating Megatron’s performance. For example, a shoulder system managed the rigid, interlaced pieces so they would not intersect when the robot moved his arm.

Because the Decepticons transform to and from military vehicles, they have less colour on their parts than the Autobots, which transform to and from cars and trucks. That helps the audience distinguish good robots from evil during fast-moving battle scenes with multiple robots smashing into each other. Megatron has a total of 1,437 texture maps. Among them are 101 bump, 732 colour, 54 dirt, 70 displacement, and 370 specular maps.

One of the biggest challenges for the animators was finding a balance between selling the weight of the robots and having them move with the agility of Hong Kong martial arts fighters. Usually, animators move heavy creatures slowly to give the appearance of weight. As a result, the animators used slow motion for some shots. They also discovered that they could move characters close to the camera faster than those farther back.

OPTIMUS PRIME

ILM built Optimus Prime’s robot body in Maya using 10,108 pieces of geometry and 1,830,898 polygons. If you were to lay all the pieces for the 28-foot robot in a row, they’d total 6,070 feet. Rather than trying to build Prime strictly out of parts from his semi-truck rig, modellers built the robot to match concept artwork and built the semi-truck rig to match the real vehicle.

So that Prime can speak and emote in tight close-ups, his face has 200 moving parts which were manipulated using 30 facial controls. Animators used a set of rigid pins inside his mouth to simulate a tongue and teeth, and an eye turbine system to create the feeling that Prime’s eyes were alive.

Get the Creative Bloq Newsletter

Daily design news, reviews, how-tos and more, as picked by the editors.

Headlights were a particular concern for all the robots. Rather than putting a light map on a surface, modellers built headlight housings for each with complex reflectors and a bulb inside. Optimus Prime’s tyre treads, however, are displacement maps. To help keep the geometry light, and to add fine details, painters working in Photoshop created 2,336 texture maps that they applied in ILM’s Zeno software.

Using a new dynamic rigging system, animators and character TDs could group pieces of geometry arbitrarily. The pieces then moved differently based on the pivots added for each group.

To transform the robots, animators moved the vehicles and the robots into key beginning and end poses and folded the robot into a shape that fitted inside the vehicle. Then the animators and character TDs moved pieces of geometry from one form into another.

Jaw-dropping Transformer statistics

BUMBLEBEE

Of all the Autobots, Bumblebee is the one that relates most to Sam (Shia LaBeouf) and Mikaela (Megan Fox), so modellers packed the robot with extra auto parts to add detail.

He’s built from 7,608 geometric pieces and 1,511,727 polygons. Throughout the film, Bumblebee the robot is always scratched and dirty thanks to 8,094 texture maps, even when he transforms from a spit-polished car. At first, the crew built clean robots, but they felt the pristine CG looked too unbelievable. During the final battle, a second, damaged model of Bumblebee replaced the original.

In addition to the digital Bumblebee, the special effects crew built a full-sized 16-foot puppet that appears in the film in a few scenes during which the robot doesn’t move much. He’s always digital when he’s running, moving, jumping, and transforming, though.

To help build the relationship between Bumblebee and Sam, animators at ILM worked first with the robot’s body posture and then with its facial animation, using eye darts, blinks, and so forth to give the metal parts an emotional performance. For reference, they shot videos of themselves and used footage of Michael J Fox in Back to the Future as inspiration.

0.77 miles: Total length of all parts in Ironhide

1,568 cubic feet of parts in Barricade

8,088: Total number of rigging nodes in Jazz

1,426,781: Total number of polys in Blackout

Ready to create your own animation? Don't forget an important first step: storyboarding.

Thank you for reading 5 articles this month* Join now for unlimited access

Enjoy your first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

*Read 5 free articles per month without a subscription

Join now for unlimited access

Try first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

The Creative Bloq team is made up of a group of design fans, and has changed and evolved since Creative Bloq began back in 2012. The current website team consists of eight full-time members of staff: Editor Georgia Coggan, Deputy Editor Rosie Hilder, Ecommerce Editor Beren Neale, Senior News Editor Daniel Piper, Editor, Digital Art and 3D Ian Dean, Tech Reviews Editor Erlingur Einarsson and Ecommerce Writer Beth Nicholls and Staff Writer Natalie Fear, as well as a roster of freelancers from around the world. The 3D World and ImagineFX magazine teams also pitch in, ensuring that content from 3D World and ImagineFX is represented on Creative Bloq.