How to draw a neck and shoulders

A step-by-step guide for learning how to draw a neck and shoulders.

When learning how to draw a neck and shoulders, it can often be challenging to show the volumes in our work, as we are used to seeing people front-on. But drawing an anatomically correct neck and shoulders will do wonders for your figure and portrait drawing so it's a skill worth persevering with.

This tutorial will take you through the steps you need to follow to draw a neck and shoulders, focusing on the individual body parts, including things to keep in mind regarding bones and key muscle groups. Want to draw the rest of the body? You'll find all you need in our collection of how to draw tutorials. Alternatively, you could try this guide to the best figure drawing books or this figure drawing tutorial.

How to draw a neck and shoulders: Things to consider

If you're learning how to draw a neck and shoulders, we recommend starting lightly with the gesture as even though the neck and shoulders seem quite chunky and static, they have a surprising amount of variety in their poses. If you are unsure of the angle of the shoulders, compare them to a horizontal to check which way they are tilting. Usually a pencil held up in the air will be sufficient.

There are three major forms at work here; the neck, the shoulders, and the ribcage. An effective tactic for drawing the shoulders at different angles and poses is by treating the gesture of the shoulders as a diamond that fits around the connected forms of the neck and rib cage. This simplifies the behaviour of the bones underneath – the scapula and collarbones – and gives us something to build on. Another issue beginners may have with the neck is making it look flat – like a paper cutout doll – as it smoothly transitions between the body and the head.

We can further push the sense of form by treating the neck as a flexible cylinder that passes through the centre of the shoulders, drawing through where it connects to the ribcage and the head as if those forms were transparent – there is no harm in erasing these early exploratory lines later.

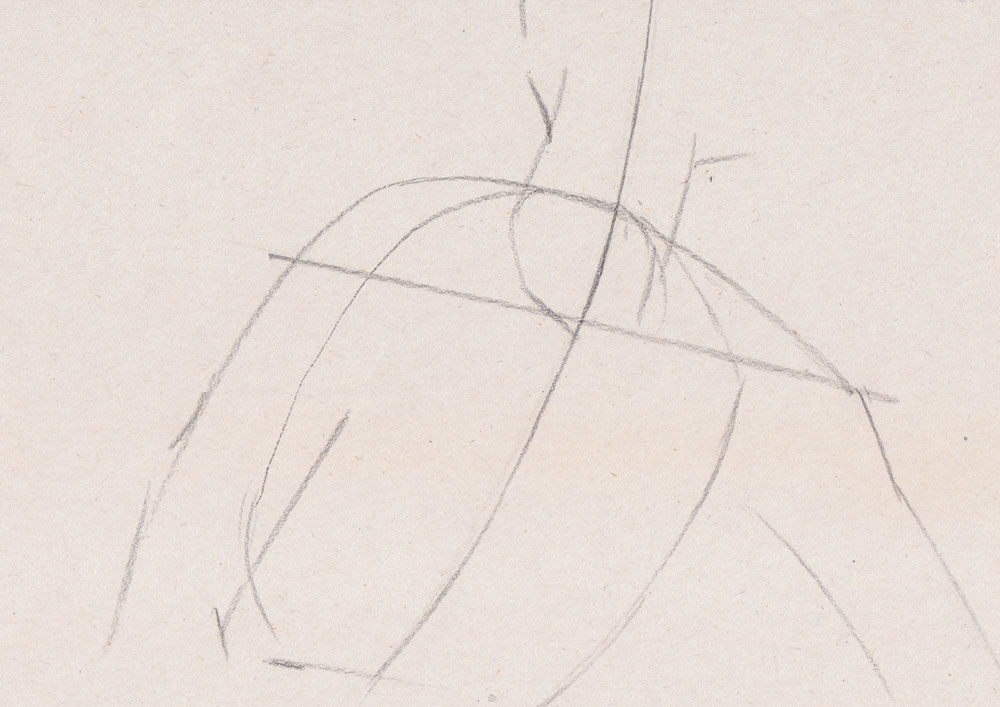

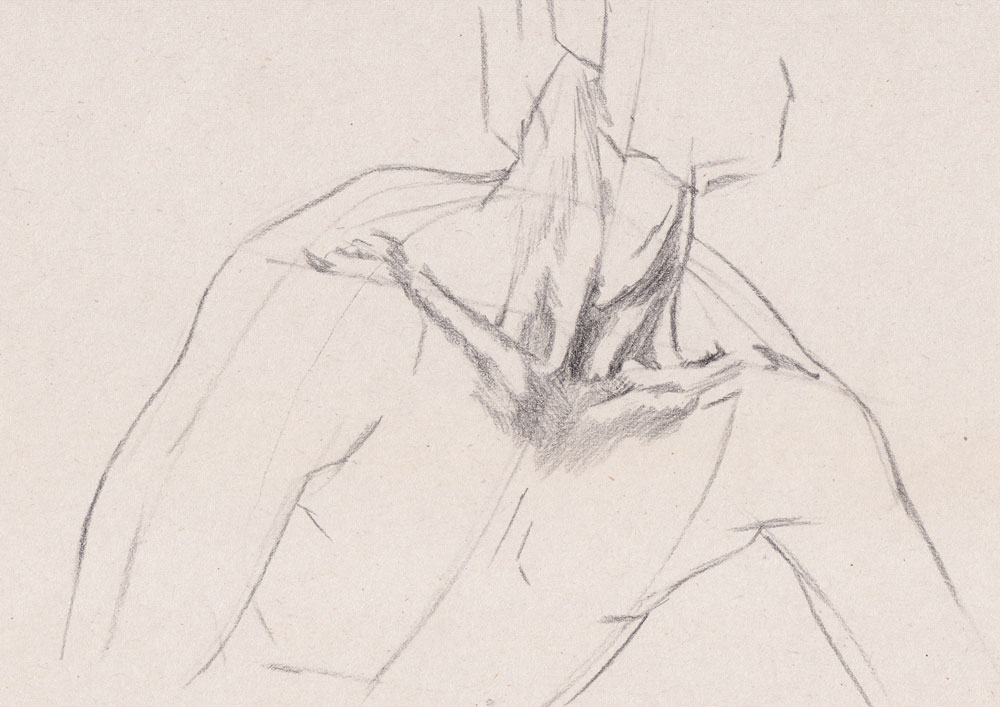

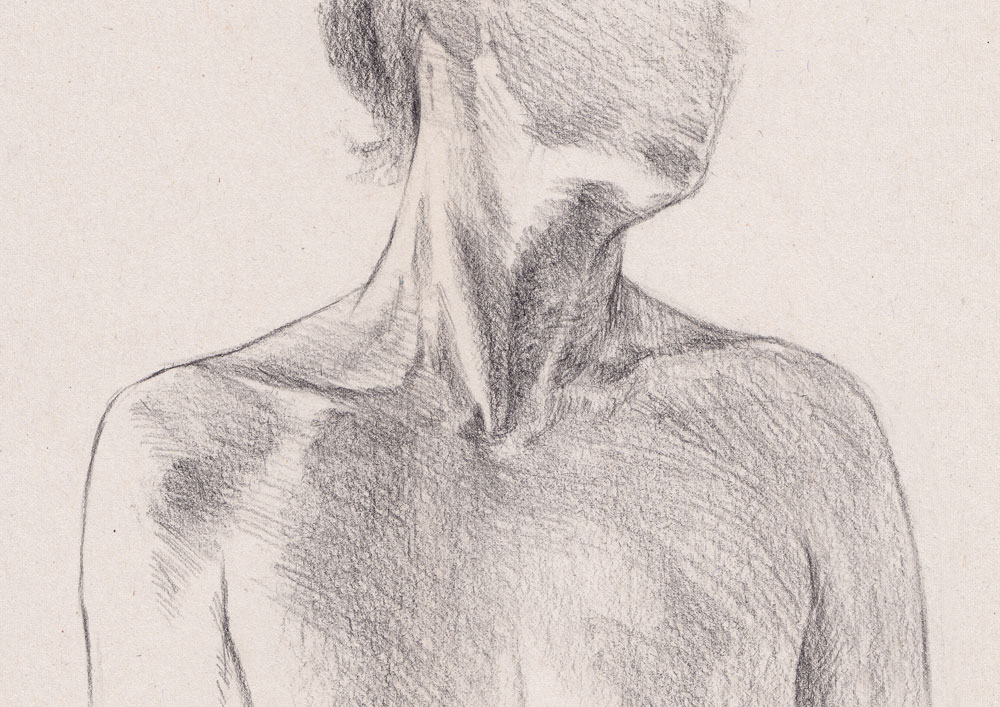

01. Begin with gesture

Starting with the gesture, we want to find the sweeping line of the neck through to the torso – this is going to describe how the head bends away from the rib cage. Then we can place the tilt of the shoulders. You can also block in the arms, showing how their gesture flows across the neck. The place where the neck and ribcage connect has been roughly indicated with a circle, forming the base of the neck cylinder.

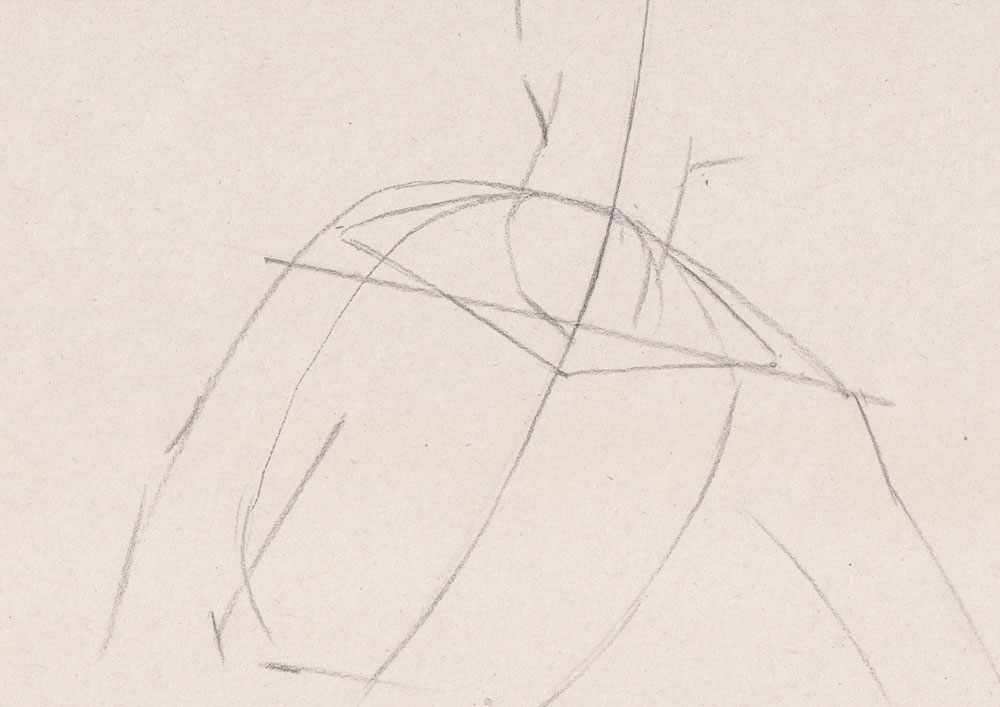

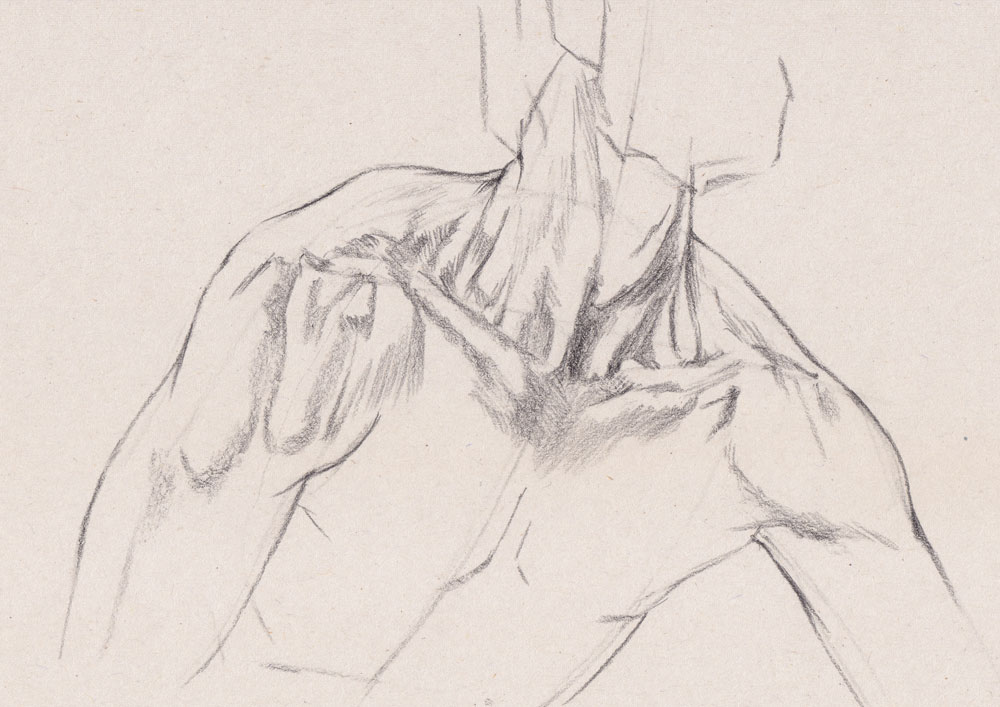

02. Mark the diamond of the shoulders

With our gesture indicating the tilt of the shoulders, we are going to mark a diamond. This is to describe the angle of the collarbones, and if we were to imagine what was going on around the other side, the scapulae at the back. These bones connect at the shoulder and pivot around the pit of the neck. Look for little bumps or shadows at the top of the shoulder and pit of the neck for the bones that describe this.

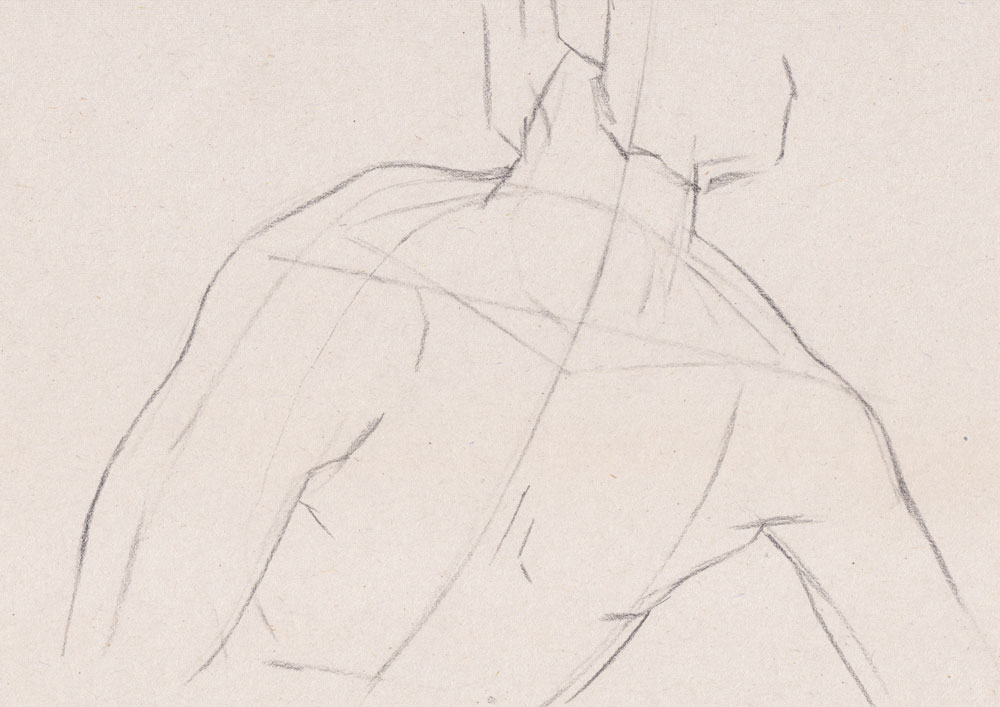

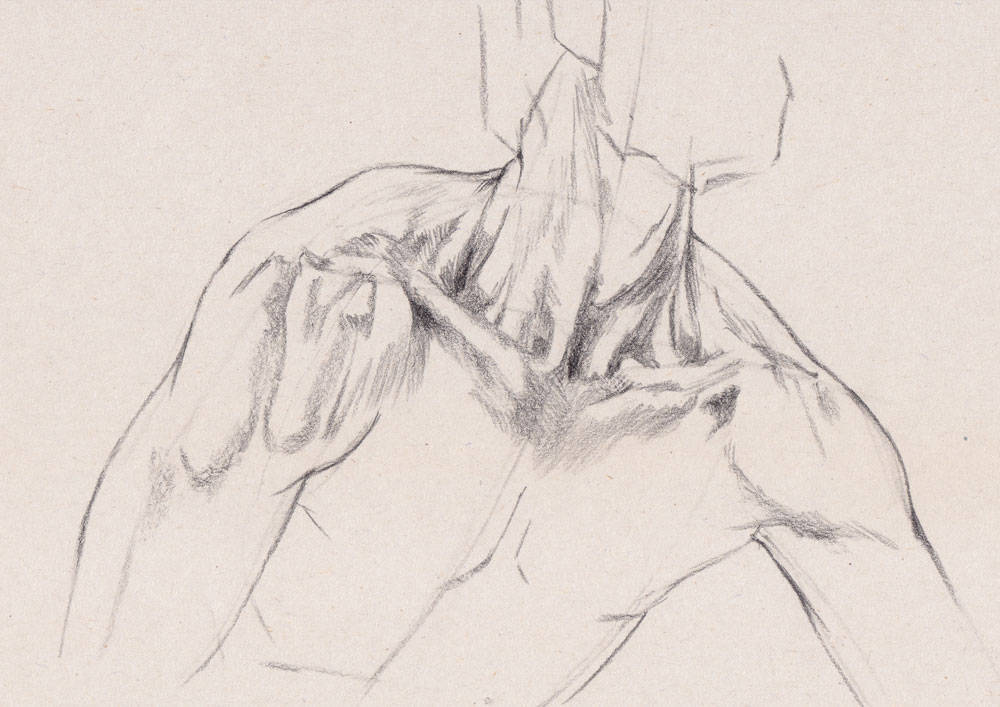

03. Sketch the major forms of the shoulders

Here we are sketching in a rough outline to contain the shoulders. Pay close attention to the negative space between the neck and the shoulders – if you are imaging a line connecting the chin to the shoulder, you can create a closed shape. At this point, the main intention is to work out the proportions of what we see and ensure things like the tilt of the shoulders look correct. Draw lightly – this is to act as a scaffold for us to build on with anatomy.

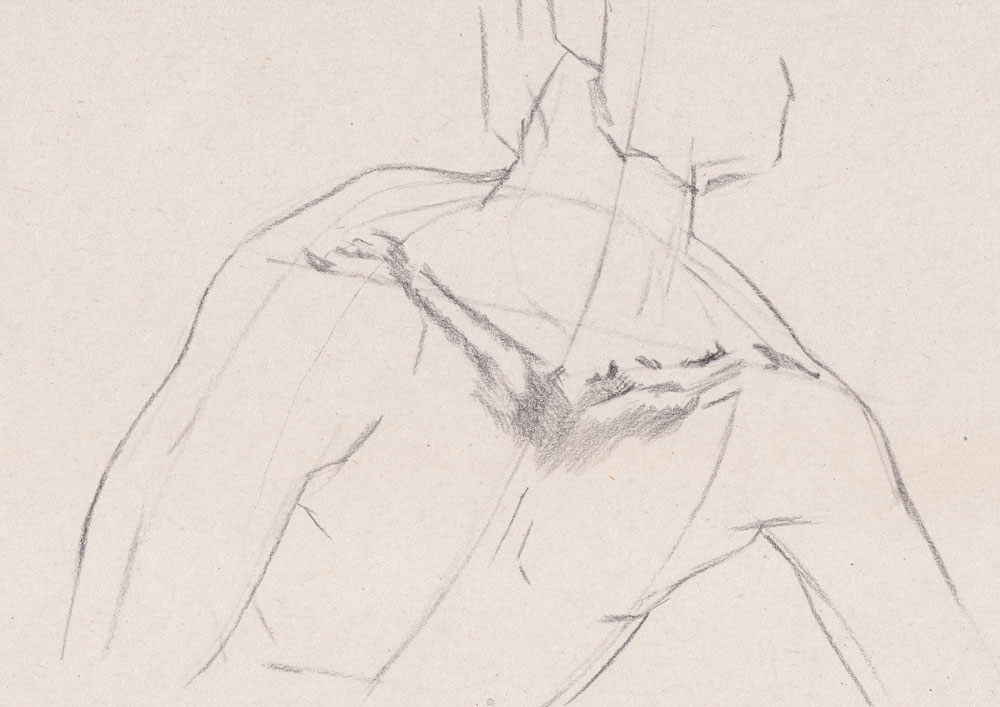

04. Observe and draw the collarbones

The collarbones are the main bones we will easily observe in the neck and the shoulders (at the back of the neck, we will see the scapulae and the spine). Look for where we can see the bone below the skin – often this is most apparent on the underside of the collarbone, at the pit of the neck and the top of the shoulder. The collarbone will have a distinctive 'S' curve, but changes a little from person to person.

05. Move onto the neck

The most visible muscles seen here are the sternocleidomastoid pair, which originate from the back of the skull, wrap around the neck and split in half, attaching to the top of the collarbone and in the pit of the neck. There are many other small muscles in the neck that we don't usually see, unless someone is very lean. This pair is essential for describing the twists and turns of the neck, and can be seen quite clearly on most people.

06. Capture the trapezius muscle

The trapezius is a very large, flattish muscle that encompasses parts of the neck, shoulder and back. It is very useful in describing how the forms of the neck overlap with the shoulder as it attaches to the back of the skull and wraps around the shoulder to the collarbone. Capturing the overlap of the neck, that sits in front here, with mass of this muscle as it wraps around to the front helps to describe exactly how the forms interlock.

07. Add the deltoid muscle

The deltoid is a muscle that wraps all the way around the top of the arm and attaches to the collarbone and scapula. On most people, it looks fairly flat, but understanding this wrapping behaviour will help you convey the subtle forms you see. It can be thought of as having a front, side, and back portion. In the centre of the top of the deltoid, the collarbone and scapula meet, creating a dimple or a bump, depending on the pose, and the model's body type.

08. Mind the gap

There are several important dimples or 'fossa' around the neck and shoulders – gaps left between where muscle groups interlock around the shoulders and neck. These spaces help imply the position of muscles without the need to draw everything. One problem beginners have with anatomy is potentially over-rendering the muscles. Always err on the side of simplicity – draw what you see. Look for small details like these to imply the behaviour of the

muscles underneath, rather than trying to draw out the shapes of the muscles.

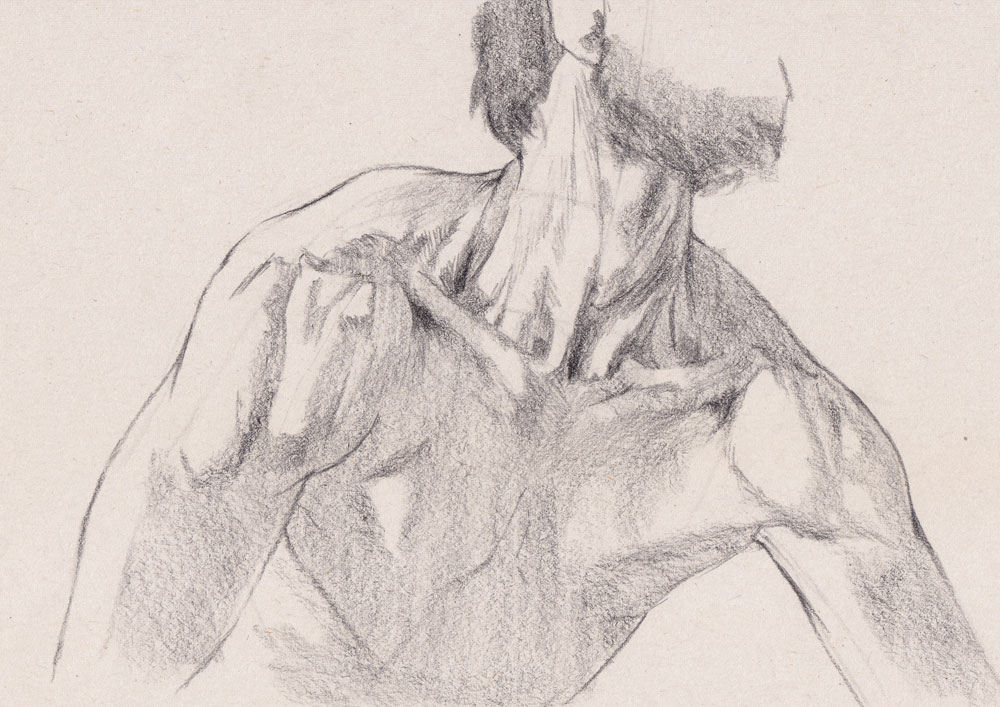

09. Lay in shadows

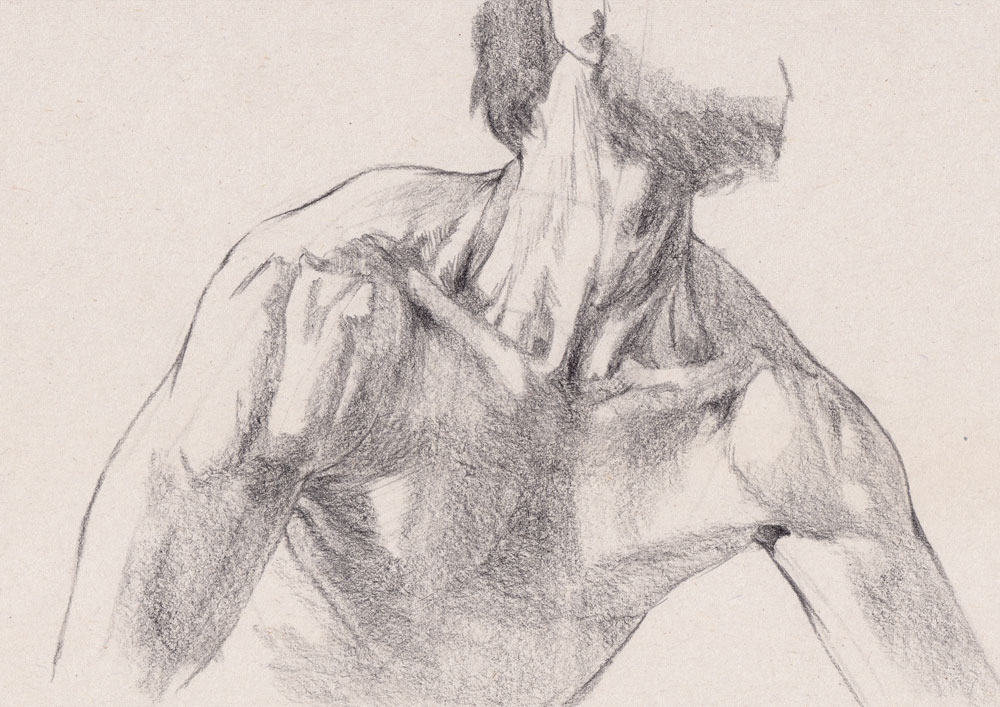

Here the shadow shapes have been blocked in. With the traversing of the anatomical features, we are tying together knowledge and observation in the drawing. Shadow is a valuable asset to describing forms, as we begin to see the roundness of the shoulders and the more cylindrical natural shape of the neck come across. Try to find one dark half and one light half to begin with; here we have kept the shading flat and even.

10. Emphasise features

We have already marked out a lot of the anatomy we can see. This is a good chance to push the shadows of any important features, such as the collarbones, or find ones you missed – for instance, here the Adam's apple has been properly rendered in, and we've clarified the overlap of the deltoid on the left shoulder. Try not to overwork these – the neck has quite subtle features – but be on the look out for tiny details. The more anatomy you learn, the better you become at spotting these.

11. Describe forms

Using hatching marks, we can start to add volume to the shadows and push some areas darker in tone. This will help describe the forms of the neck and shoulders on top of our flat layer of shading. This area of the body has quite complex and changeable surfaces. Think about how the skin and muscles are wrapping around the neck, and transitioning down to flow around the shoulder. Ensure your marks follow the surface of the skin, like a sculptor's hands. Thinking about the direction the muscles are pushing in helps with this too.

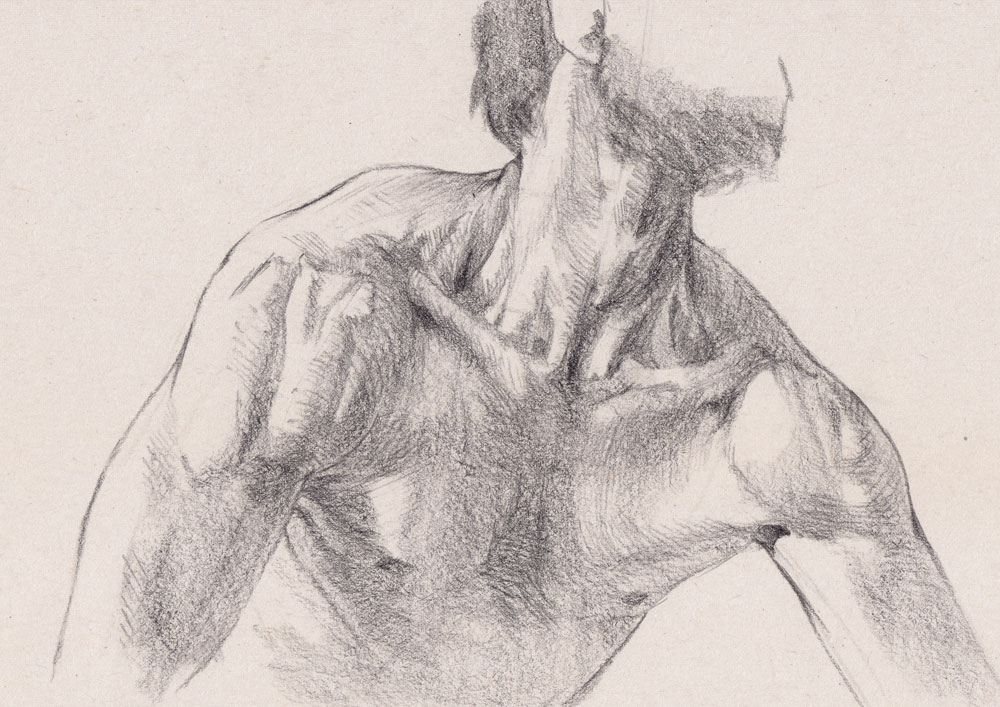

12. Tighten up the outline

This is our final pass around the outline of the body. The neck and shoulders give lots of excuses to vary your lines – for instance, thickening and losing the edges of the outline in shadow areas such as under the armpit. In light areas, it is a good idea to sharpen lines, or even break them in a few places. A uniform outline around our figures gets boring very fast, and these small changes in line-work become especially effective when we are drawing figures with less obvious musculature, as shown in the second image.

13. Add finishing touches

In this final stage, we'll work around the drawing looking for the last few details to include. This is also a good time to emphasise the edge of the shadow. Make the border a bit darker, to improve contrast, and use small amounts of hatching to create softer transitions on the rounder forms such as the deltoid. Like with the outlines in step 12, looking for variety in the edges of the shadows creates a more interesting end result.

This content originally appeared in Paint & Draw: Oils. You can buy the Oils bookazine here. Or explore the rest of the Paint & Draw bookazines.

Read more:

Get the Creative Bloq Newsletter

Daily design news, reviews, how-tos and more, as picked by the editors.

- How to draw a head: A complete guide

- How to draw an arm

- How to draw hands

Thank you for reading 5 articles this month* Join now for unlimited access

Enjoy your first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

*Read 5 free articles per month without a subscription

Join now for unlimited access

Try first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

Lancelot Richardson is an artist, painter, and freelance illustrator based in Brighton, UK. He tutors life drawing at independent art school Draw Brighton, and teaches in their online Patreon courses. He is also a freelance writer, producing articles on art and drawing. He works in both traditional and digital mediums.