Cache in on the BBC's performance booster

How using caching can massively boost your site's speed.

Last year during a user testing session for the BBC News app, one of the users made a comment that has really stuck with me. They declared: “I like to flow”. I don’t think there’s a better summary of what performance means to our users. On a fast app or website, the user can flow around, interact and engage with the content.

Flowing experiences are good for site owners too. A fast-flowing experience helps users achieve their goals and in turn we achieve our organisations’ goals. Amazon and others have demonstrated the strong link between performance and user activity: as the wait for pages goes down, the amount of time and money the user spends goes up.

Cut the distance with a cache

Caches are created when a small amount of something is stored closer to where it is needed, normally to prevent rework. For example, if I am eating Skittles, I tend to pour a few into my hand and then eat from there. In effect, I am creating a cache of Skittles in my hand as it’s quicker to eat them that way than going back to the packet.

This same pattern is used in technology. There are three caches we have to consider:

- Server caches: Cached data on the server, such as the results of database queries

- Network caches: Caches built into the network, sometimes by the site operator (known as a reverse proxy cache), but more often by ISPs or other networking providers

- Browser cache: The browser stores files on the user’s hard drive for reuse by the user

Caching can make for a huge performance improvement; at the BBC I have seen caching increase performance more than 20 times in production code. It is beneficial for site operators too. With caching, more users can be supported by the same hardware. This reduces the cost in hardware per user and therefore reduces website operating costs.

Design with the cache in mind

For it to be effective, we want to use cached data as much as possible. To extend the Skittles analogy, if I want a blue Skittle but I don’t have any blue Skittles in my hand (aka my cache), I will have to go back to the packet. This is known as the ‘hit rate’. It’s a ‘hit’ when the item is in the cache and a ‘miss’ when it’s not. We want a high hit rate so the cache takes most of the load.

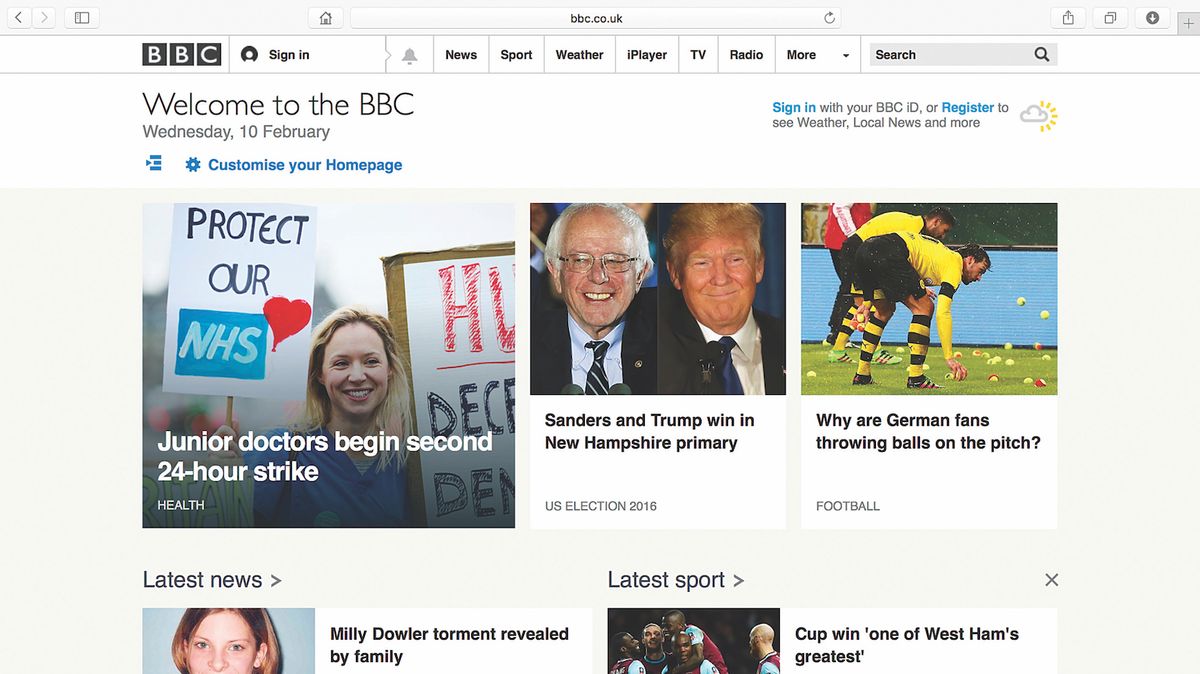

One of the simplest methods to increase hit rate is to reduce variation. Stretching my Skittles analogy a bit, imagine if all Skittles were red. That way, any Skittle in my hand would be a cache hit; I would never need to go back to the packet. Applying this to the web, if we can give the same page to as many users as possible, the cache becomes more effective as more requests will hit the cache.

Get the Creative Bloq Newsletter

Daily design news, reviews, how-tos and more, as picked by the editors.

Cache HTML for a short time

So that’s the theory. Let’s get practical. Let’s start by looking at caching the request for the HTML. Caching of all file types is controlled using HTTP headers. The headers are meta data (data about data) sent from the server to the browser and visible to all the network hardware in-between. To tell the world it has permission to cache our pages and to share that cache between users, we set the following header:

Cache-Control: public, max-age=30Here, we have also set a time limit: the maximum amount of time the cache should reuse this page for, in seconds. For this example, I have set it to 30 seconds.

By setting the page to ‘public’, the user’s browser (and any hardware along the way) will keep a copy. So the first page load will make a request, but all page loads after that will reuse the original response, until the time limit is reached.

The effect of network hardware along the way can be profound. Many large networks (such as ISPs) will have a cache shared between users. Mobile operators also use this technique heavily – for example, to cache and recompress images served over 3G. Site operators can also place an HTTP cache in front of their service. This is what we have done at the BBC.

Cache static assets for ages

A technique we use a lot at the BBC is to treat static assets (like images, CSS and scripts) differently to how we treat pages. Caching HTML pages for too long can result in users missing content updates but we can take advantage of this behaviour when it comes to static assets.

At the BBC we send all static assets with a maximum age of 31,536,000 seconds set in the cache header. This ensures the assets are cached for 365 days. In effect, assets are only requested once. This is good for performance but bad for flexibility as changes to that asset will take a long time to get to the user.

In order to work around this, every time we release a new version of a page, we change the URL where the assets are kept. This trick means that new changes are put in front of users immediately but we still get the same performance benefits.

Final words

Caching in order to enhance website performance will in turn lower operating costs for our websites and preserve our users’ flow, leading to a great user experience.

This article was originally published in issue 279 of net, the world's best-selling magazine for web designers and developers. Buy issue 279 or subscribe to net.

Want to learn other ways to give your sites a speed boost?

Jason Lengstorf is a developer, designer, author and friendly bear. His focus is on the efficiency and performance of people, teams and software. At IBM, he creates processes and systems to Make The Right Thing The Easy Thing™. At all other times, he wanders the earth in search of new and better snacks.

In his workshop Modern Front-End Performance Strategies and Techniques at Generate New York from 25-27 April 2018, Jason will be showing attendees how to improve perceived load times – how long it feels like it takes to load a page – as well as actual load times, using only front-end techniques including:

- The skeleton loading pattern

- Better loading for static assets

- Lazy loading

- Service workers

- Better build processes and more!

Generate New York takes place from 25-27 April 2018. Get your ticket now.

Related articles:

Thank you for reading 5 articles this month* Join now for unlimited access

Enjoy your first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

*Read 5 free articles per month without a subscription

Join now for unlimited access

Try first month for just £1 / $1 / €1