Why you should embrace design thinking

Design thinking is a powerful idea that portrays designers as masters of the universe, but what does it really mean?

“I don’t know if IDEO could have saved the American auto industry, but we would have started with foam core and a hot glue gun.”

This is one Tim Brown’s more flippant quotes, but it does give you a quick snapshot of what design thinking – one of the pervasive buzzwords in the creative industries – is all about. You can just picture IDEO’s CEO and his team sketching, sticking things together, and crafting dozens of different cars, roads, robots and factories with the aim of getting Detroit back on track. It could even work, who knows?

The line comes from Brown’s book, Change by Design, which explains the concept of design thinking in somewhat more sober detail as well: “Design thinking is a human-centred approach to innovation that draws from the designer's toolkit to integrate the needs of people, the possibilities of technology, and the requirements for business success.”

Imagine using your design skills to improve the provision of healthcare, revolutionise agriculture or change how schools teach

IDEO, with Tim Brown at the helm, has helped make design thinking one of the most relevant and compelling concepts, not just in the creative industries, but across the economy. It’s an exciting idea that is being embraced in just about every sector, and gives creatives every reason to be optimistic.

Sure, the skills you’ve learned as a designer can be used to create a new logo, brochure, website or ad campaign. But just imagine using them to improve the provision of healthcare, revolutionise agriculture or change how schools teach. IDEO has worked in all of these areas, and one of Tim Brown’s projects is a guide to designing for the circular economy. It’s worth checking out.

Iterate wildly

Coming from a product design background, IDEO began laying the groundwork over 25 years ago. Today the company runs shoulder-to-shoulder with dozens of other big creative outfits that all embrace similar ideas. During his time as CEO at Wolff Olins, Ije Nwokorie (who is now senior director at Apple) helped make design thinking part of the branding agency’s core practice. For him, it consists of three elements: exploration, hypothesis and creation.

“It has to have exploration, so you’re going to have to go out and understand people who are not you. It has all the techniques of ethnography, of people-watching and so forth,” he explains.

Get the Creative Bloq Newsletter

Daily design news, reviews, how-tos and more, as picked by the editors.

“The second thing is that it believes the past is only useful for stimulus and inspiration, but the answer is going to be something we’ve never seen before. Therefore it has to be hypothesis-led and iterative in nature. You don’t say one plus one equals two, you say: Here are 18 ways we can solve this problem, let’s put them out there, let’s test, let’s iterate and let’s make them better and let’s find one solution.”

The past is only useful for stimulus and inspiration, but the answer is going to be something we’ve never seen before

Ije Nwokorie

He continues: “And then the final thing is that design thinking says those things have to be designed. The design bit of it means that we need to use the fundamental tools of design to solve those problems. What are the tools of design? They are form and shape and movement and time – and that we have to craft something that is different from anything that has ever existed before.”

Branding a language

An example he cites from Wolff OIin's repertoire is branding dotdot, Zigbee’s open source language that Internet of Things devices use to communicate with one another.

The branding is actually derived from the code and is very simple. It’s made up of these three keystrokes :|| and can represent a fridge that orders your milk or a dryer that knows how wet the laundry is because the washing machine has told it. And while the whizzy bits in your kitchen talk to each other, the branding tells consumers that compatible appliances can have a conversation. Which in itself begins a conversation…

How is communicating this notion an example of design thinking? Nwokorie explains: “If you take the problem as, ‘How do I communicate the Internet of Things?’ you would come up with a different solution than ‘How do I solve the problem that people don’t quite understand that these things work together?’

The visual language comes from a piece of code. It’s two dots and two slashes, but that’s also the branding. It communicates and it’s iconic and it stands out, but its fundamental purpose is to solve the problem of ‘How can we help people think about and build things that work together?’”

Perhaps one of the reasons design thinking is so prominent today is that communication, the sharing of information online and social media have become such powerful forces in today’s society. Designing something that can be understood intuitively, easily and naturally is one of the greatest goals of design thinking – the design itself communicates its purpose.

More than a feeling

Next to that comes the experience of using or consuming what has been designed. Lippincott is a design consultancy that does a lot of branding, believing that design thinking extends from how a business is run through to how its customers experience it. Legal, compliance, HR, marketing, manufacturing – anything a client does can be improved with design thinking. But whatever the touchpoint, emotion is a key ingredient.

“Design thinking should be a 360-degree activity, incorporating all aspects of the business or brand but keeping the customer at the heart of the process. The task is to create something that has great utility, yet is beautiful at the same time. These two elements married together create an emotional bond with the customer,” explains Lee Coomber, creative director at Lippincott.

Design is to business what evolution is to nature; it enables brands to change and survive

Lee Coomber

After all, it’s because of aesthetics and not just practicalities that designers will be involved. He continues: “Design is to business what evolution is to nature; it enables brands to change and survive. At a time when so much of our lives is going to change as a result of advances in technology, designers need to make the world not only work better, but be beautiful as well.

"Design thinking can allow design to be more influential, less visual and more a means of opening up opportunities for businesses by building holistic experiences and emotional bonds.”

Design for all

It’s not just the big players like IDEO, Wolff Olins or Lippincott that are inspired by design thinking. Many design studios and boutique agencies are fully on board. APFEL (A Practice for Everyday Life) is based in London and has a core tenet of design thinking built into its name.

“For us, ‘design thinking’ is really just a catchy term for the range of methods and approaches that we put into practice within our everyday lives – for navigating the world around us, learning and developing, and experimenting. We approach design projects and problem-solving in a way that feels instinctive, starting with research and investigation, conversation with the people involved, testing ideas, considering different contexts, and responding to feedback,” says co-founder Kirsty Carter.

The studio worked with Mae Architects on MyHouse, an affordable housing project that enabled buyers to design their new home using a set of predefined components: slot this kitchen onto that dining room… oh, and let’s have a downstairs loo.

“Mae’s work on the project is an example of design thinking in practice: it identified an important area of need, and considered the challenges faced both by potential buyers and by construction companies,” says Emma Thomas, APFEL's other co-founder. “Using this information and research, it collaborated directly with a fabricator to come up with a model that would offer the flexibility that makes self-build housing so attractive, whilst removing the need for buyers to manage the design and building process themselves.

“Our role was to help Mae create a public face for the project, to make it accessible and appealing to their target audience. We needed to convey the possibilities that MyHouse offered, in the absence of any images of the finished houses, which were still in development at the time.”

Counterculture and free tacos

Over in Toronto, the advertising agency OneMethod employed design thinking so effectively at a self-promotional pop-up event that it ended up founding a restaurant. If you went to the event and bought a piece of art by one of OneMethod’s creatives, you received three free tacos. The experience was so authentic, visitors demanded the company set up a permanent taco restaurant and now OneMethod runs two La Carnita locations. Plus, it still does ad campaigns for clients.

For another Toronto studio, Blok, design thinking is about expanding the parameters of a problem and finding the less obvious solutions to explore. “It is honing our intuition and our nonlinear thinking in order to explore openly, flowing between the simple and the complex in order to rethink the parameters themselves. It is not simply about what we do but how we think and what is necessary to make it happen. Every project we work on begins and ends with this process. It is our means to mining depth and finding the authenticity from within,” says founder Vanessa Eckstein.

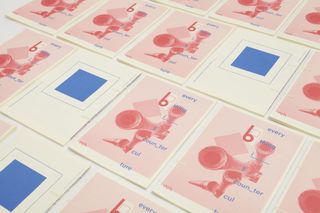

It’s an approach the studio used when asked to design an issue of Wayward Arts magazine devoted to the topic of ‘counterculture’. The creative wall – analogous to Tim Brown’s foam core – was a key part of the toolkit as the magazine was developed.

“Counterculture is so much part of our DNA that we spent six months researching expansively and putting what we found up on our creative wall – where everything flows and lives – moving images and words, poems and historical timelines up and down, looking for those un-obvious but provocative connections to reveal themselves,” says Eckstein.

Consulting the cultural anthropologist Dr Bob Deutsch, Blok brainstormed around the idea of what culture and what the opposition, duality, tension and contradiction of a counterculture really mean, then explored imagery and ideas in juxtaposition with one another. The outcome was a magazine surprisingly close to how the studio might express its own identity.

Butcombe Brewery

A final example to check out comes from Halo’s rebrand of Butcombe Brewery in Bristol. As well as giving the brewery and its six main products a new identity, Halo suggested the company create a special range for the craft beer market, came up with the ‘78’ branding and worked with the brewery on 12 concept ales celebrating 1978 – the year Butcombe was founded.

Butcombe is now producing a new beer each month because Halo showed them how to reach a new market, proving that design thinking can be an irresistible force in marketing.

No limits?

Design thinking is such a powerful concept that it is replacing other methods of running companies. As design thinking becomes the buzzword of the 21st century, management consultants and management thinking are seen as a relic of the last century.

Huge corporations like IBM, Procter & Gamble, Marriott Hotels and Fidelity are integrating design thinking with their internal processes. However, when anything becomes part of a process, initiative can be stifled.

Alongside design thinking we also have to make sure we’re talking about wild imagination, radical ambition, and sometimes magic

Ije Nwokorie

No matter how hard you sit down and try to be a design thinker in the boardroom, having fun, playing, splashing paint, going crazy and just plain winging it are aspects of creativity that you can’t build into a formalised process. When design thinking becomes a process, we end up iterating on and optimising existing designs rather than coming up with radical new ones.

“Think of design as an entirely rational discipline, and that it can’t afford to be otherwise, and we’ll end up merely optimising everything as opposed to having an optimistic and imaginative view of the future,” says Nwokorie.

“Alongside design thinking we also have to make sure we’re talking about wild imagination, radical ambition, and sometimes magic. Those things don’t quite live comfortably in the way design thinking is defined in many organisations.”

Related articles:

Thank you for reading 5 articles this month* Join now for unlimited access

Enjoy your first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

*Read 5 free articles per month without a subscription

Join now for unlimited access

Try first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

Garrick Webster is a freelance copywriter and branding specialist. He’s worked with major renewable energy companies such as Ecotricity and the Green Britain Group, and has helped develop award-winning branding and packaging for several distilleries in the UK, the US and Australia. He’s a former editor of Computer Arts magazine and has been writing about design, creativity and technology since 1995.