What happens when tattoo design meets illustration

Why more creatives are crossing over into tattoo design.

Around 2010, I was hanging out with a group of tattoo artists, discussing the rising popularity of tattooing. We thought it was a wave that would soon crash, leaving only the diehard behind. How wrong we were.

In the last seven years, the tattoo world has exploded. With the help of television, as well as social media, tattoo art has been dragged out of the shadows and into the global spotlight. Where once it was looked on as an outsider art form, it is now considered at the forefront of creativity and development.

If you look back over the history of art, whenever an art form becomes popular, it attracts artists from outside of the medium – artists who recognise that there is potential to play and expand their own creative path.

This is true for the current trend in tattooing; one where commercial illustrators and designers are crossing over into the tattoo world, and drawing on trends such as watercolour tattoo art. And conversely, where tattoo artists are lending their skills to commercial projects.

Designing the outcome

Nomi Chi, a tattooist and visual artist based in Vancouver, showed an interest in illustration early on. At the tender age of 12, she was trying to sell commercial art, and at 15, Chi discovered tattooing through a combination of a rebellious teenager’s attraction to the subversive side of art, plus the burgeoning growth in tattooing and the run of tattoo-related television shows and social media.

Chi attended university, where she studied illustration, but over the years found that she had distanced herself from illustration as an applied art, and moved into an area that straddled the line between gallery art and illustration.

“Tattooing seemed like a pretty organic development, although at the time I was determined to do concept art for video games and movies,” says Chi. “I had a lackadaisical apprenticeship, which I landed through sheer luck. At the time, I had very little knowledge of tattooing or tattoo culture, and I had only ever seen a tattoo machine once before.”

Get the Creative Bloq Newsletter

Daily design news, reviews, how-tos and more, as picked by the editors.

Martha Smith, a tattoo artist based in London, who studied Illustration at Camberwell College of Arts, also found the move into tattooing a natural progression of her artistic development – the freedom of process found within tattooing being just one aspect she was drawn to.

While at college, Smith quickly realised that the course was incredibly concept-led. Preferring process-based work, she started printmaking, and it was with this medium that she began developing an aesthetic that would later translate into tattoos.

“I always had an interest in tattooing, but before I attended art school, most of the tattoos I saw were traditional, or realism tattoos, which never really appealed to me,” she says.

“Then, Sang Bleu Magazine came out and I was exposed to new artists such as Liam Sparkes and Maxime Buchi, who came from illustration and graphic design backgrounds, but were tattooing in a similar way to the way I printed. It was then that I thought it would be something I’d like to pursue.”

Smith points to many parallels between the process of printing and tattooing, citing the permanence and strength of line, the understanding of the tools and the medium as examples.

“There are also many similarities in the way a brief is structured in tattooing and illustration,” she adds. “It felt like a natural pathway into full-time illustration work, but with constant briefs and a sustainable income.”

Guaranteed income

Both Chi and Smith moved into tattooing while keeping their illustrative careers going at the same time. The guaranteed income from tattooing gave them the freedom to pick up side work in visual art and illustration, something which is echoed in many other tattoo artists’ careers.

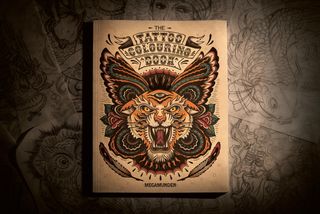

The converse of this approach is seen in artists such as Ollie Munden, who works as a lead designer for ilovedust, as well as having his own studio, Megamunden. His beautifully illustrated book, The Tattoo Colouring Book, came out in 2013, and was an opportunity to combine his love of illustration and tattoo design. Unlike Chi and Smith, Munden doesn’t actually tattoo.

Aasen Stephenson is another tattoo designer, but not a tattoo artist. His work came to prominence when he used a tattoo machine to etch his designs onto a range of stylish leather shoes.

“I’d been doing some bits of artwork for Jeffery West, and we started to throw around the idea of customising a shoe once it had been made in-store, in front of the customers,” he recalls.

“It took a while to figure out what would work and give the best results, but engraving seemed to be the best option.” Stephenson tried using several engravers until he hit upon the idea of using a tattoo machine, which gave good results, “and also looked cool in-store.” Although new to tattooing, Stephenson created all the designs freehand, without using stencils.

“I just ordered a kit online,” he recalls. “Originally, we went with the cheapest, as I still didn’t know if a tattoo machine would give the best results. The kit was £55, you can imagine how bad it was! But it was a start and since then I’ve bought better machines.”

With previous experience as a body piercer, Liz Clements took a slightly different route into tattoo design. Having enjoyed the studio environment of piercing, she did a pop-up shop with Occult Tattoo in Brighton, who ended up taking her on as an apprentice.

“A lot of my illustrations were inspired by tattoo culture, so in terms of the themes there isn’t a lot of difference,” she says. “I have always really loved traditional tattoos and I think that’s evident in both my tattoos and my illustrations.”

Transferrable skills

But what can artists interested in combining the two mediums expect when they start to move between them? As with all artistic endeavours, there is no limit but the imagination. However, Smith believes that her college introduction to illustration helped make the transition easier.

“My studies certainly helped with tattooing,” she states. “Illustration projects have a quick turnaround with a quick brief. This helped when it came to working alongside customers to develop their custom tattoo designs.” Smith also cites printmaking as having helped her tattooing.

“For one, it strengthens your arm and shoulders, as well as getting you used to the permanence of an image. People that are used to drawing in pencil, or painting in oils, have a transformative way of creating, where things can be edited, evolved and manipulated. With a woodblock, or a piece of lino, once that mark is carved, it is carved, much like a tattoo,” she explains.

As with any crossover in art, the challenge is in identifying what works in the change of mediums, and what has to be adapted. For Chi, these differences are nothing more than a mindset – a different approach to a similar outcome. “My tattoo process is very particular. I try to be very transparent with regards to my interests and the stylistic direction in my portfolio,” Chi explains.

“When I tattoo, I feel people know what they’re getting. When I am taking project requests, I look primarily at the subject matter and secondarily at the narrative behind the subject, if my client provides one. When working as a visual artist, I work best when I’m given some preferences for subjects and stylistic direction, and am allowed to compose the elements however I see fit.”

Design challenges

Clements found the move across to tattooing a little challenging. “The practical side is totally different, so I have to balance the complexity of my designs to correspond with my skill set, which I have found quite tough,” she says, adding that designing to fit a body part is totally different to working on a flat surface.

“I often do three or four tracings when I’m creating the stencil for tattoo, so the image kind of builds up in layers, and you have to rearrange as you go through the design process. For this reason, Clements thinks that tattoo design is a lot more complicated and long-winded compared to designing for print.

For Stephenson, moving completely into the world of tattooing is a path that remains unexplored for the moment. “I’ve thought about it a lot, but not made the step yet,” he says. “I guess it’s because I enjoy getting tattooed. I think if I learned how to tattoo, I may not look forward to getting tattooed.”

Explaining this idea further, Stephenson recalls his previous experience of learning the guitar. “I was always in awe of people who played, but then as I started to learn, I viewed guitarists differently,” he says. “I’d think to myself, ‘Ah, I know how to do that now!’ It kind of took the magic away. Therefore, I guess, I will always want to get tattooed, rather than actually do it,” he smiles.

But this hasn’t stopped people getting Stephenson’s designs etched into their skin. Besides his paper cutting work, he has also drawn up a few designs specifically for tattoo purposes. “I love the idea of getting my work tattooed on skin, it’s such an honour for someone to give you that trust, to be with them forever,” he remarks.

Munden has also had his work tattooed onto clients, but has reservations about this approach. “Prior to creating the book, I’d designed quite a few tattoos for people. It was, and still is, something I’m on the fence about, as I’m not a trained tattooist,” he explains. “There are so many amazing tattoo artists out there, I find it a bit backwards coming to me for the design. I always tell anyone that asks that it is the most expensive way to get a tattoo and probably not the best.”

Munden did, however, design his left sleeve piece, and learned a lot about placement and how much detail should be included, or left out, along the way. Since the release of The Tattoo Colouring Book, he has also started to see more of his designs tattooed on other people.

“I’ve seen the book pop up in various tattoo parlours and I’ve had lots of people tag me on Instagram in pieces they’ve had tattooed from the book. Some people write to me and ask permission, some send me a picture once it’s done, either way it’s all good with me. I love seeing that the work has been well received and people are getting tattooed,” he grins.

When to say no

Managing expectations and knowing when to back off a brief is important, whether you are working on or off skin. As Chi points out, tattooing is high demand work. Unlike a commercial brief, you are often expected to come up with ideas on the fly. But at the end of the day, a brief is a brief and knowing your limits is important.

“At the moment, I struggle to keep up with demand, as a result I have to turn down most proposals which are sent to me,” says Chi, who does not show her drawings to clients prior to the day they’re getting tattooed. “I have had many frustrating years of back and forth interactions between clients, and from that I developed my intake process and bedside manner,” she explains.

Though Stephenson doesn’t tattoo, the approach to his illustrative process is similar to that of a tattoo artist, where compromise and reworking are often a necessary evil.

“All my work is commission-based, so I do have to go through it with the client to ensure that we are both happy. Sometimes customers can come in with some crazy ideas, which is great! But once on paper it doesn’t always work,” he admits.

Over time, Stephenson has learned to avoid briefs that he can’t do technically, or doesn’t want to put his name to as he doesn’t think they’ll work. “Getting things wrong is all part of the journey,” he says. “And being self-employed, there is no boss you can ask when you get stuck. Over time you learn and hopefully it gets easier!”

Munden has also learnt what will work and what won’t over the years. “In my commercial illustration work, I’ve passed projects over to fellow illustrators because I’m too stretched for time and would rather someone else give the client a better end result. Other times, I don’t feel I’m right for the project,” he explains.

“It’s important the work I do take on is close to my interests,” he says. “I want to make sure I’m giving each project 100 per cent dedication. It’s a nice position to be in as I’m not solely relying on Megamunden to pay my bills, but it also means anyone coming to me for what I do will get a quality end result. I make sure of that.”

So what does all this mean for artists, on skin and off? It’s unnatural for creativity to be limited, and art should ideally have no boundaries. Therefore, any crossover or middle ground for artists to explore should be nurtured and encouraged.

And with the art world turning towards tattooing as a new field for expansion, the crossover is creating a generation of artists who continue to blur the lines. This allows for more growth in creativity in general, and a lot more people sporting beautiful designs that will stay with them forever.

Related articles:

Thank you for reading 5 articles this month* Join now for unlimited access

Enjoy your first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

*Read 5 free articles per month without a subscription

Join now for unlimited access

Try first month for just £1 / $1 / €1