Launch a world-class design studio with the ‘three Fs’

Celebrated designer Stephen Doyle shares his pro tips for making it in the design industry.

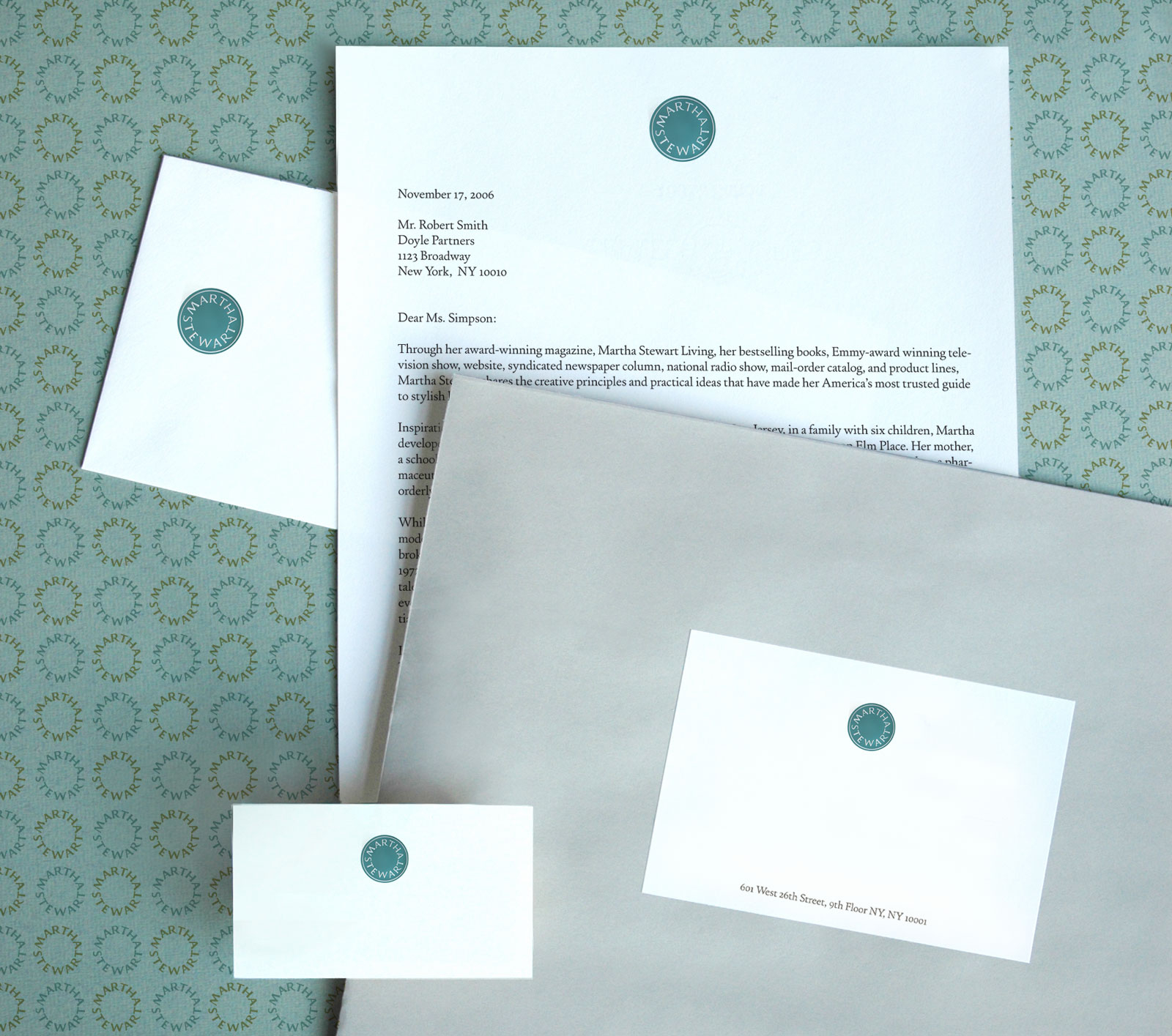

Stephen Doyle, creative director of New York-based design studio Doyle Partners, has been called a magician more than once. An outspoken advocate of the joy of designing under duress, his work goes beyond the brief, defying client expectations with unexpected solutions.

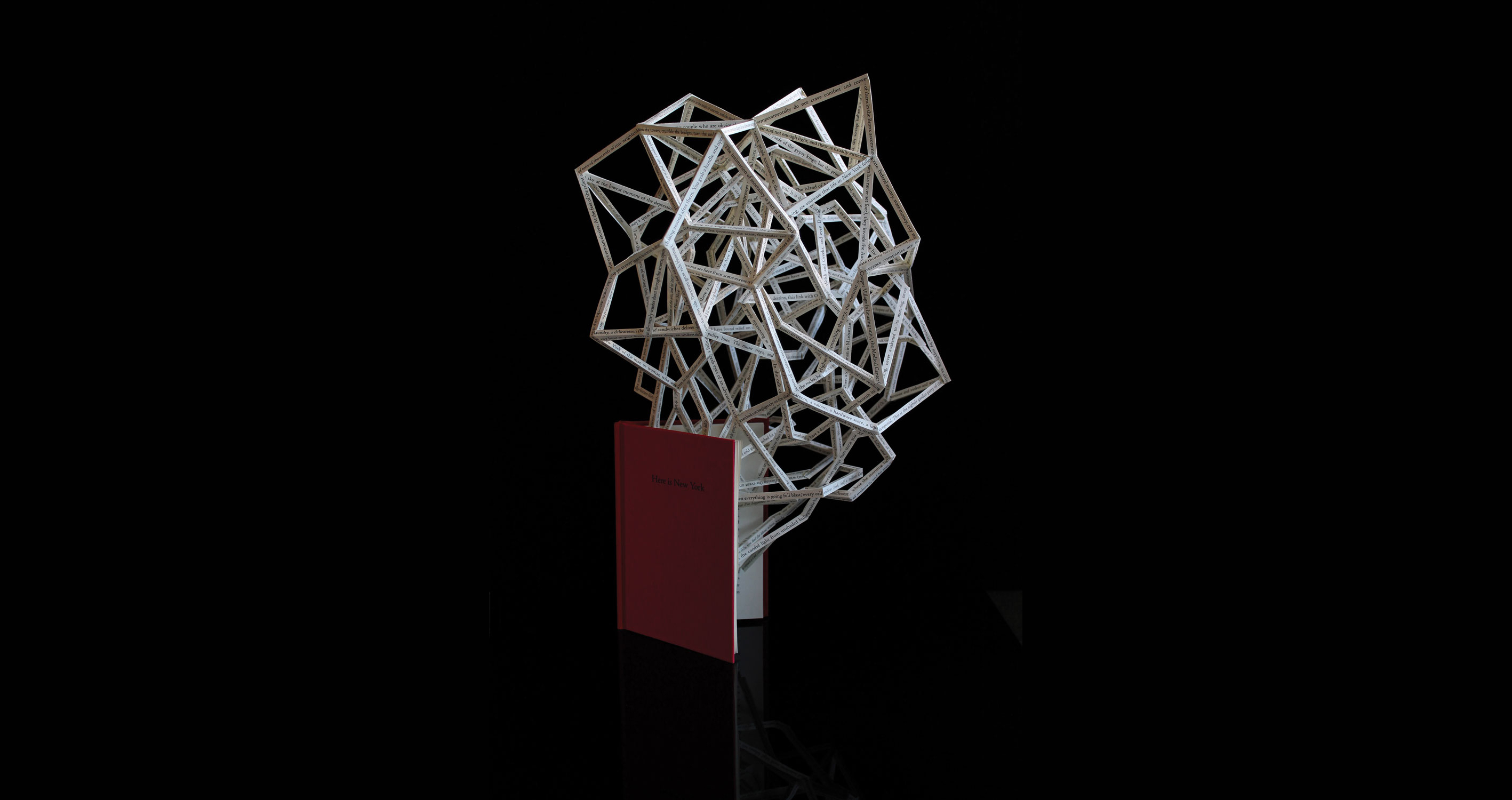

If you’ve seen his intricate paper sculptures, you’ll understand the magic part. Meticulously constructed from lines of text cut from books, the narrow strips elude gravity and show no glue or pencil markings.

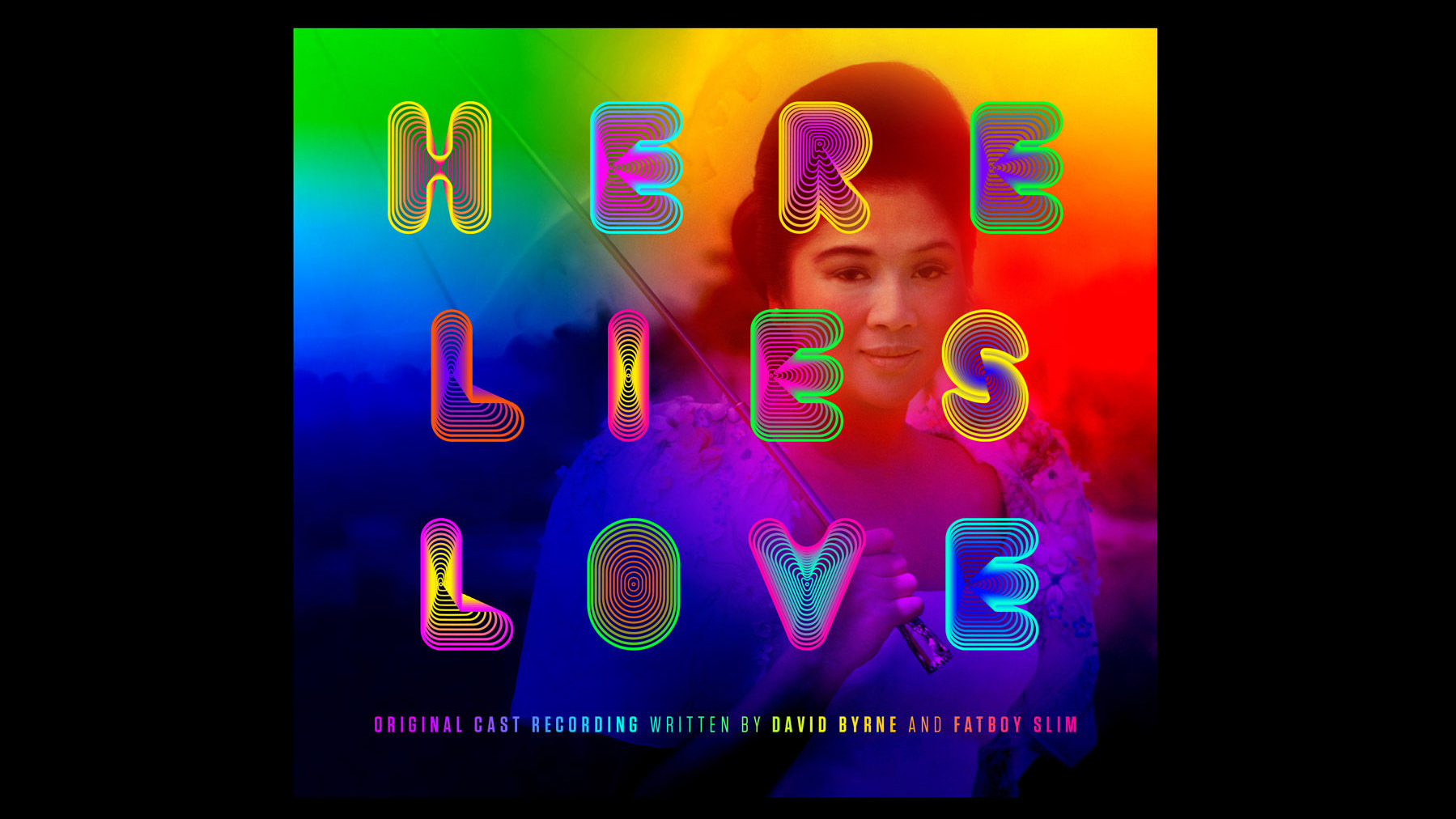

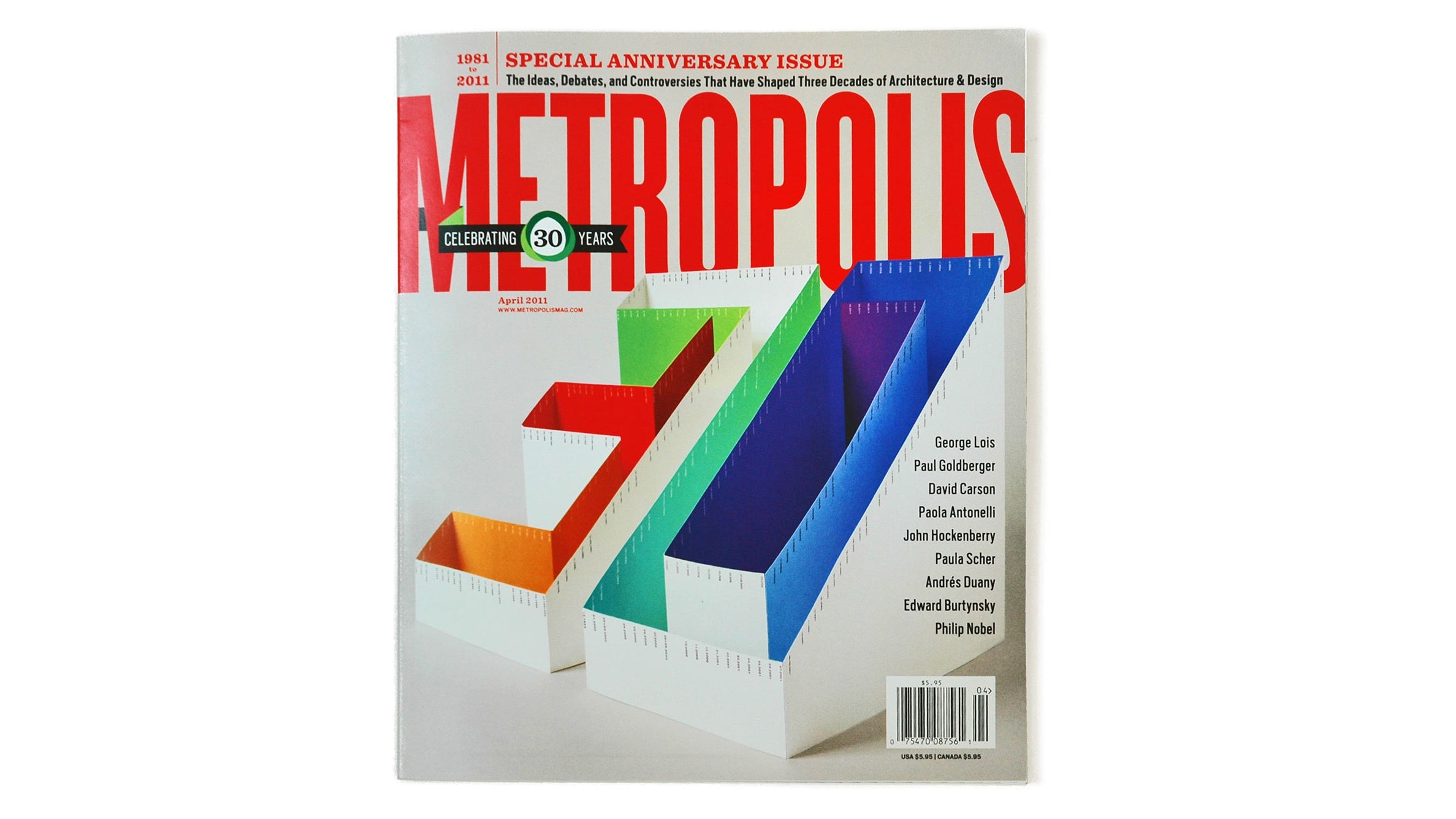

And that isn’t where the magic of Doyle’s work stops. In a world of visual overload, his studio's projects – which span everything from graphic and environmental design to video and sculpture – succeed in forcing viewers to stop and think.

Unsurprisingly, he’s picked up more than a few awards for his services to design. In 2010 Doyle was honoured at the White House with a National Design Award, and he’s been recognised with a 2014 AIGA Medal for being the ultimate 'designer's designer'.

Doyle’s speaking in Dublin at OFFSET 2018 – where we’ll be reporting live. We caught up with him ahead of the event to find out what it was like studying and working with bona fide design legends, and what it takes to launch a world-class design studio of your own…

Starting out in design

You studied under the likes of Herb Lubalin, Seymour Chwast and Milton Glaser, and then worked with Tibor Kalman at the start of your career. How did working with such celebrated designers shape your work and thinking in design?

Stephen Doyle: My most impressionable class at Cooper Union was one co-taught by Milton Glaser and Henry Wolf. Milton, larger than life, hailing from the Bronx, towered over Henry, refined and delicate, with his Viennese sensibility.

Get the Creative Bloq Newsletter

Daily design news, reviews, how-tos and more, as picked by the editors.

The class was editorial design, and at break time, the students would line up at the water fountain and down aspirins. The disagreement between these two design champions was at times ballistic!

What kind of a career path could this be, I wondered, when these two titans couldn't agree on a single thing. Just the career for me, I decided, because there didn't seem to be any rules whatsoever: just free-wheeling open-eyed opinion.

The opposite of science-based and factual fields, design seemed to be a wide-open frontier with endless possibilities, wide open to reflection and imagination. My kinda playground.

You’ve talked before about honing your typographic craft at Rolling Stone. Looking at your career as a whole, how important was this time for you? And how important is it for designers to spend time perfecting traditional skills in today’s fast-changing design landscape?

My first job, at Esquire, and originally working under Milton Glaser there, was where I learned to hone the skills of cooperation. Working as part of a design team is very different from the experience as a solitary flier in school.

Telephone skills, collaborating with editors, assigning illustration and photography – all these simple tasks were full of lessons about how to get what you want from others – superiors, comrades and freelancers. It's one of the pleasures of a design career, because it is so very social, and one is exposed to experts of all sorts to learn from.

'Read this' is sometimes better whispered than shouted

Stephen Doyle

My second step was working at Rolling Stone, and it was here that I began to focus on typography. At the time, I thought that type and design that was the hook for me. But ultimately I learned that the appeal was to be able to refine the narrative – that type and layout were in the service of seduction: 'Read this' is sometimes better whispered than shouted.

This attention to craft really helped me build out – and differentiate – my own toolkit, and set me nicely apart from many peers. I became not the 'type guy', but better yet, the 'language guy'. It seems, for me, it wasn't so much the typography as the end goal – it was the words.

How to launch your own studio

Why did you decide to leave M&Co to found your own studio? What did you want to do that you couldn’t working in Kalman’s studio?

After a year and a half as art director at M&Co working with Tibor the brilliant, I was challenged by a client that I brought in. He asked me why I had an 'agent' who was taking a large commission from my design work. Hmmmm.

I had always fantasised about having my own studio, and I thought, at 28 with no wife and no kids, it was time to make the leap, so that when I failed I would never wake up at, say, 50 years old, and regret never having tried it.

Partnering with my friend Bill Drenttel, an ad guy with a business sense, I put all my savings into an account with his name on it too. Terrifying.

Our credo from the start was to abide by the rule of the 'Three Fs'. Fun. Fame. Fortune. Pick two – any two. But we could not accept any job that promised only one of these.

Eventually, I became romantically involved with one of my clients, who became my wife, and that added yet another 'F' to the equation, but we're not going to go there right now...

What advice would you give to other designers who are thinking about launching their own studios?

Launching your own studio is, as always, a serious commitment. Consider yourself, and identify your shortcomings. Now go out there and find that kid from school, or from your social circles who has those skills that you don't. Team up with her or him: you'll be stronger and more versatile, and have twice as many contacts to start with. Pledge honesty with each other or call it off.

Work your brains out for five days a week, and take the weekends off. Feed your mind. Don't look at design blogs; go to museums.

Clients have the option of hiring any number of designers for any job. Be really nice and really fun and funny, if you can. Enchant them, and seduce them. Clients want to enjoy the process of design (often their only creative breakout) as much as you do. They want to be involved in the process, and friendly beats arrogant every time.

How to get a job at Doyle Partners

And what about people who want to work for you? Doyle Partners works across everything from environmental projects to video, sculpture and conventional graphics. What do you look for in the portfolios of would-be new hires at the studio?

The first test for me is the resume. I scan it for typos, and a single error here means the candidate is voted off the island. Or if, as sometimes happens, the cover letter says, "I've always wanted to work at Pentagram…" Well, that's a disqualifier too.

There is no magic bullet for preparing your portfolio. I look for imagination and appropriateness. Lots of portfolios have lots of style, but the ones that are actually intelligent are wonderfully rare.

Being able to design like your teacher doesn't cut it anymore. It's individuality and passion, craftsmanship and artistry that cut through the fog for me.

Can you share any key portfolio do and don’ts for a designer preparing their portfolio for you?

- Rafia, bay leaf, dried orange peel or anything that might fall into the "potpourri" category fastened to what you think is the "design" category.

- Orgami of any kind. I'm sorry, my friends, but it's really over, and no matter how hard you worked on that calendar, it's not getting produced.

- Which reminds me: calendars! Especially with different fonts for each month. Really, get over it. We have phones and no wall, desk or mental space for them.

- Long verbal rationalisations for dull creative work. Design work should be explanatory, and if you need to quote Roland Barthes or Umberto Ecco, you have ultimately failed.

- Individually wrapped samples. Makes the presentation noisy, and the dismissal part of the interview interminably long.

- Hands (or any extremity for that matter) holding posters aloft, books extended, etc. Keep yourself mostly out of your photos of your work. Put your heart in, keep your hands out.

How to stay fresh as a designer

Finally, you’ve talked before about the joy of designing under duress. How do you navigate the line between fresh thinking and failing to find the right solution for the client?

Staying fresh and coming up with unexpected solutions is a challenge that we all face. To keep my batteries charged, I keep adding to a very robust scrapbook collection – both analog and digital.

Keeping your eyes open when flipping through foreign newspapers and snapping photos of signs, materials, juxtapositions; collecting scrap from unexpected sources online – you can build yourself a personal arsenal of inspiration that helps to get the juices flowing.

I've got stuff stored that took me an entire decade to find the project worth appropriation. But thoughtful thievery from unlikely sources is one of the best tools we have. And don't forget to eat breakfast!

Related articles:

Thank you for reading 5 articles this month* Join now for unlimited access

Enjoy your first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

*Read 5 free articles per month without a subscription

Join now for unlimited access

Try first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

Julia is editor-in-chief, retail at Future Ltd, where she works in e-commerce across a number of consumer lifestyle brands. A former editor of design website Creative Bloq, she’s also worked on a variety of print titles, and was part of the team that launched consumer tech website TechRadar. She's been writing about art, design and technology for over 15 years.