"I used to illustrate my invoices to get noticed," says Kit Hinrichs

One of the world's leading graphic designers reflects on his 50-year career.

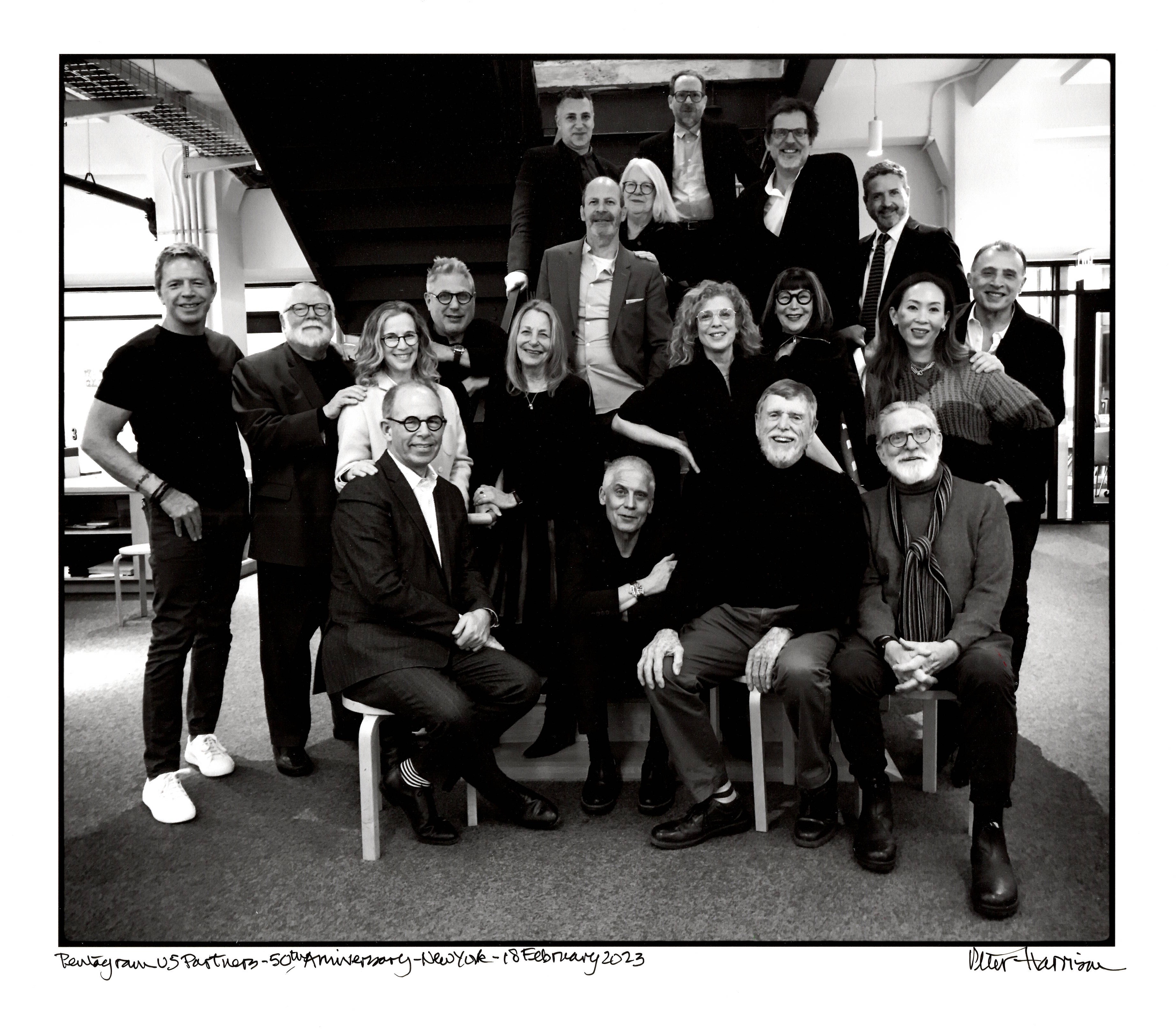

Kit Hinrichs is one of the world's most influential designers. He was previously a partner at Pentagram, is now the principal of Studio Hinrichs, and has a list of accolades as long as your arm, including an AIGA medal and inclusion in the permanent collection of the Museum of Moden Art in New York.

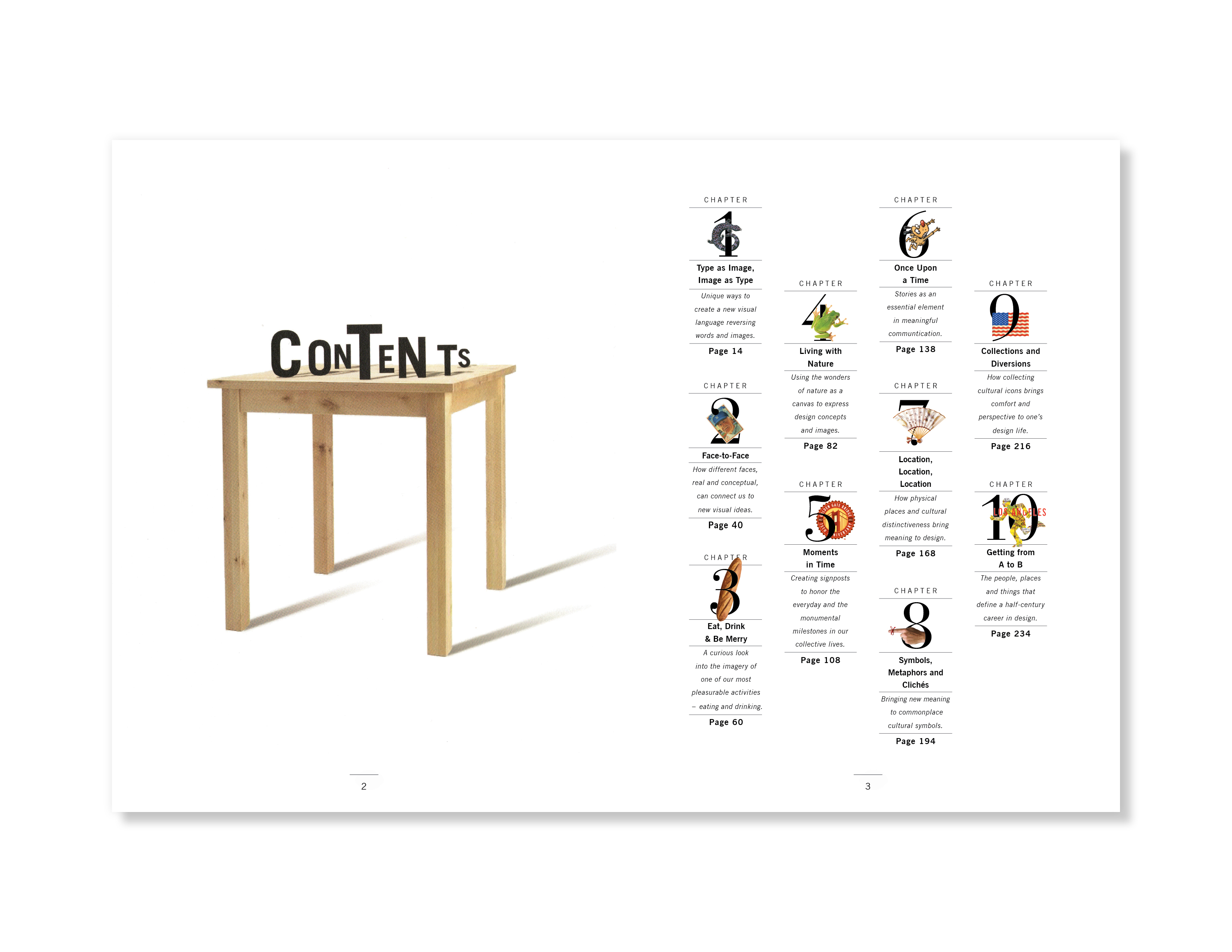

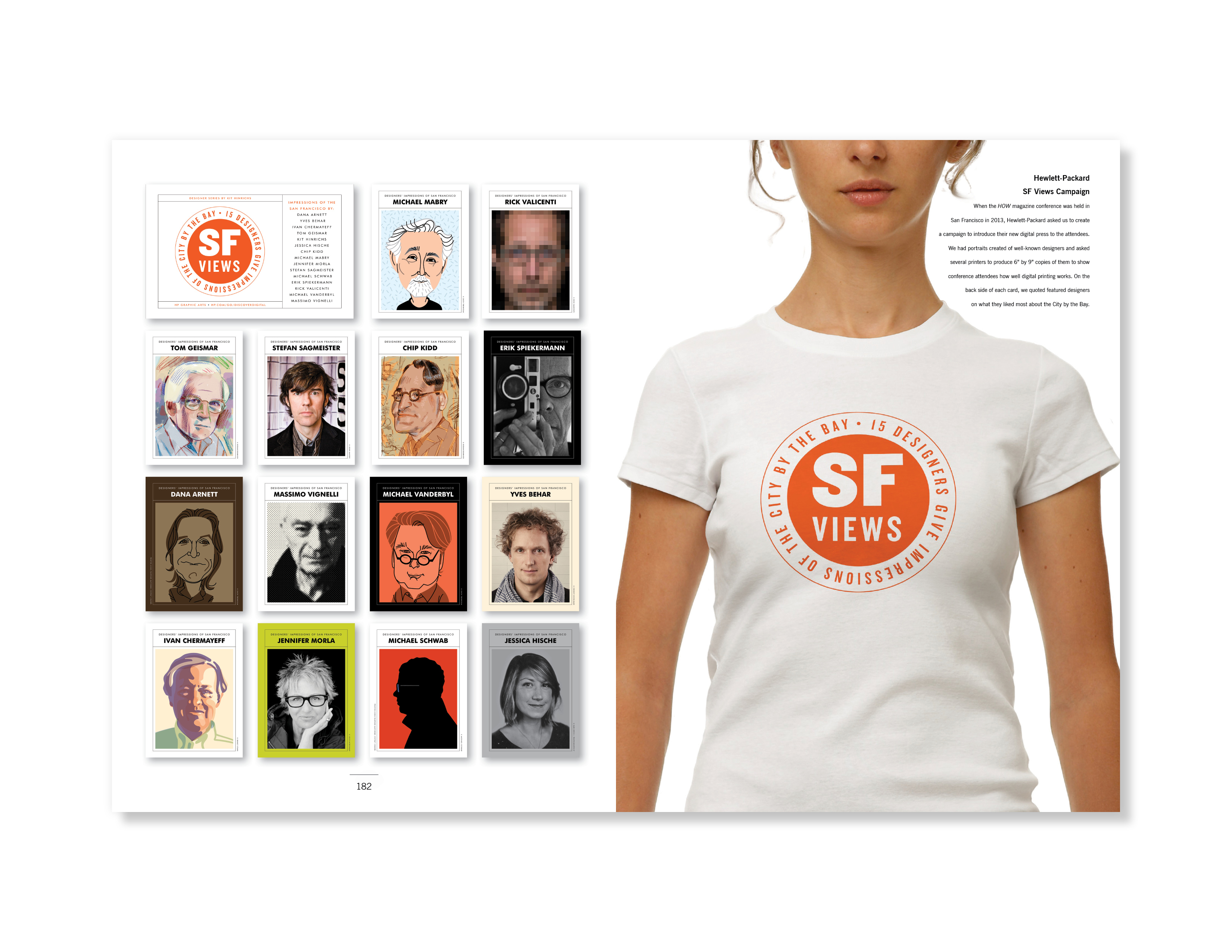

His new book, Narrative Design: A 50 year perspective, showcases the work he's produced over a jam-packed career of over half a century, and is neatly divided into 10 sections, with each section tackling a different area or theme. Face-to-Face deals with how difference faces, real and conceptual, can connect us to new visual ideas, for example.

As the book so beautifully shows, the thing that unites all his work is a love of stories, a passion for finding the engaging story, and discovering the best way to communicate that. "I named this thing Narrative Design because I think that storytelling is such a strong, powerful way to communicate all kinds of things, not just things in a brochure or a website," he says. "It's effective in all kinds of communication, so I find it helps to always find the story."

I spoke to Hinrichs recently to find out more about the power of stories, his early days as a designer, his time at Pentagram and just some of the projects he's created over the last 50 years.

Have you always thought about design in terms of telling stories?

I know when I was a kid, I would go to the store when my mom was shopping, and I would go to the section that had comic books or popular mechanics or other things that had highly visual items in them and told stories. And I found that very appealing even as a small child.... stories that I found as a child have stayed with me through my life.

Even in school, I would find myself always trying to make a story more effective, and making a story if there wasn't one. And I found that was an interesting way to communicate. It was very simple. Not everyone uses that technique to communicate, but I found it amazingly effective.

Of all the projects you've worked on, which are you most proud of

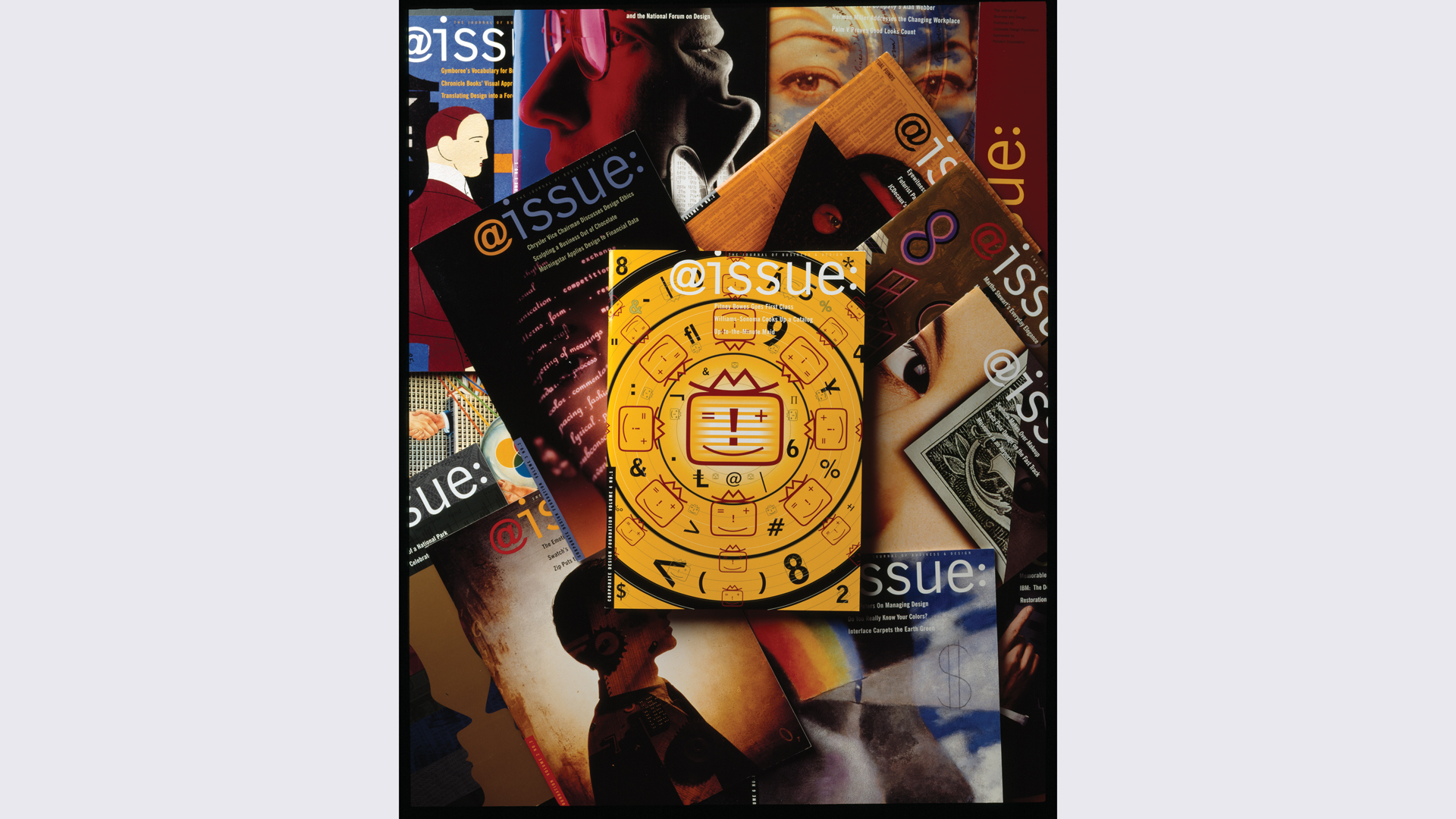

That question is like asking, 'which is your favourite child?' There are many. One thing is a magazine that we have produced for about 15 years called @Issue. It was an opportunity to tell stories, but they were all business stories or visual stories that related to business. It was a way that designers could understand business and business could understand what designers were trying to do. And so it was quite a wonderful series for a number of years, which then got translated into a website as well. It's been ongoing for us, and is a favourite.

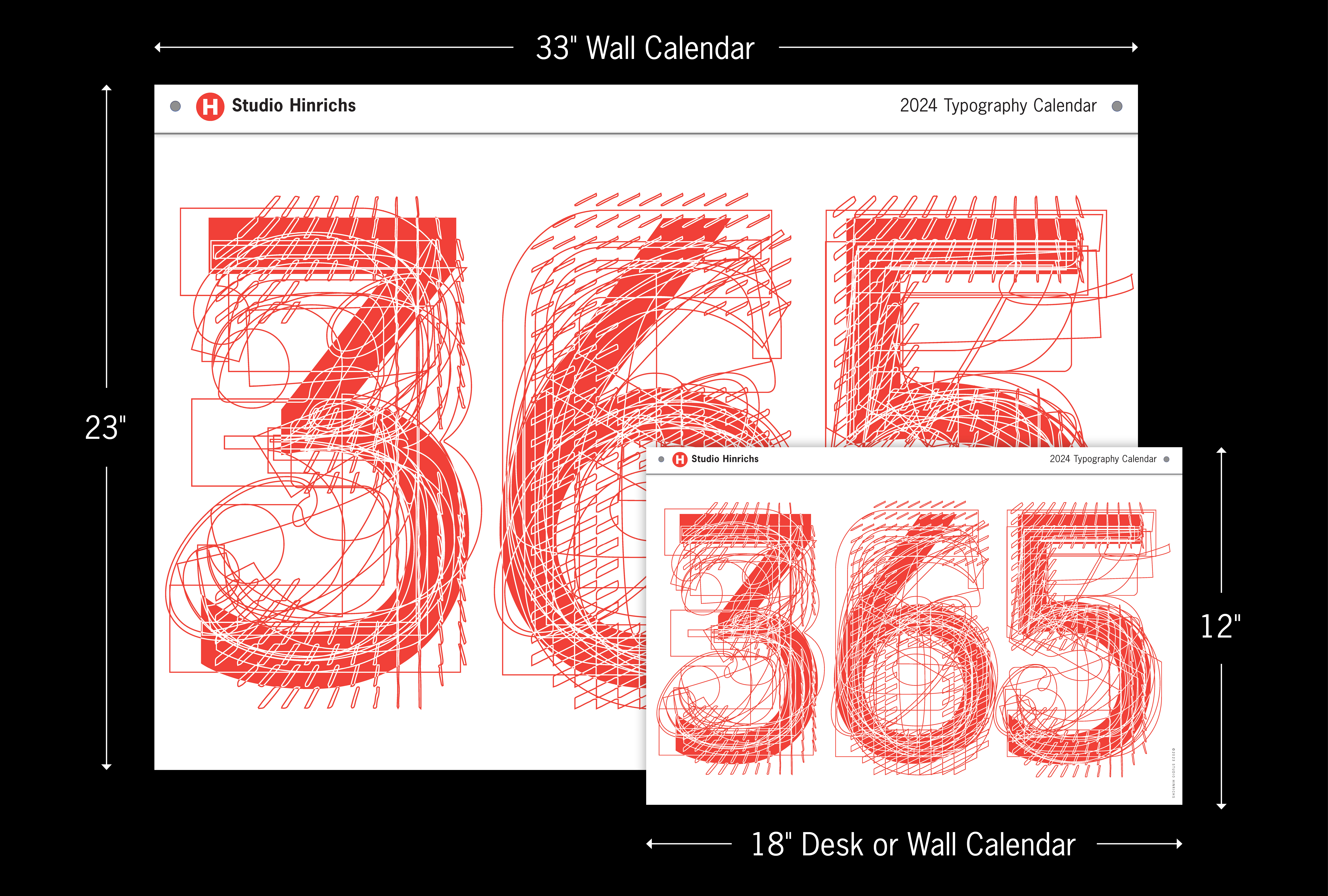

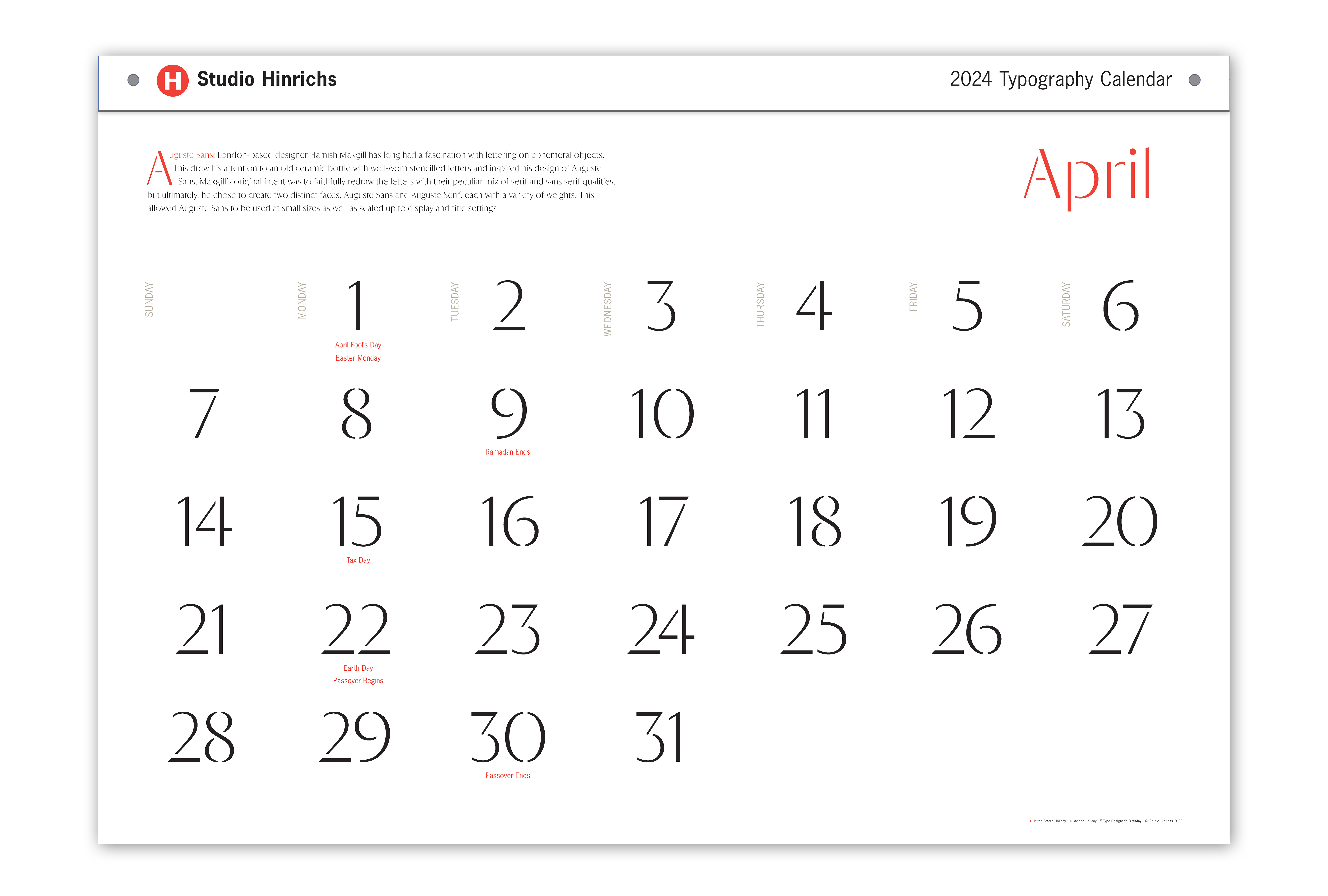

Why did you start your typographic calendar?

This relates to narrative design. If there is a story, it always makes things more powerful for people. I've always been very interested in typography. And I kept thinking as more and more people outside of the trade began to use different faces... they were not really knowledgeable about what was going on, and why they picked a particular face. Why one was better than another one, what the background was to it.

And so I felt the idea that we could communicate with a very simple calendar that also had, who had designed the calendar, what period of time was it done, what technology was used. All those things helped inform the person looking at the calendar as to what typeface was, what its origins were, and that I found just fascinating. And now, after 22 years of doing it, it continues to be something that people always comment on, they always loved the idea of looking at the background to a typeface, not just a typeface itself.

Do you think people look at the information on the calendar or do they just look at it and think it's pretty?

I think it's both. It looks great on the wall, and I think that's certainly part of its appeal, maybe its major appeal. But I think when there's at least a secondary story to kind of back some something up, it gives people a little more knowledge. I love to educate people... I thought this was a nice way to keep you engaged in it, not just what day it is, but also, what is the typeface you're using? What is that character? When was it created? Who did it? There's some interesting things in there that I think always influence how you understand information.

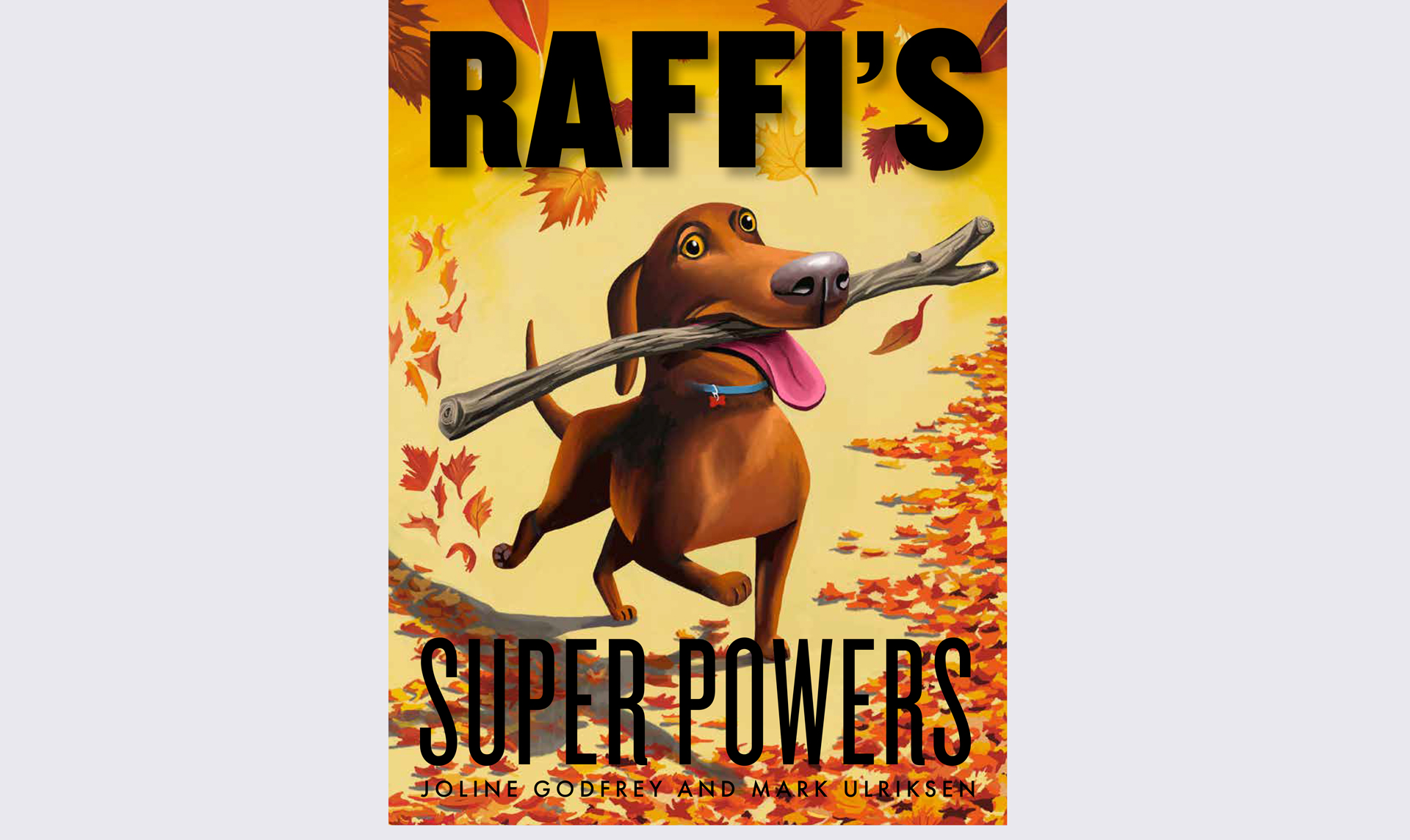

You're working on a children's book at the moment, how are you finding it?

I probably always wanted to do a children's book and just didn't have a client who assigned me to do one and unfortunately, most of my work is not self-generated. It is usually a client saying 'we need to solve this particular problem'.

We do have a client now who was trying to raise the financial feasibility for kids to understand finance and how things work. And so there was an opportunity with his client to do a children's book, and really a series of children's books, which helped communicate different aspects of finance. And so this thing started, it's a dog named Raffi and his master, a young girl called Sandy, he tells a very simple story and he experiences things with Sandy, and he learns all kinds of things from it. We had a wonderful illustrator Mark Ulriksen, who was known for having multiple New Yorker covers, and he loves dogs, loves baseball, and is just a wonderful artist. And so we had a great time. And it's turned out amazingly well.

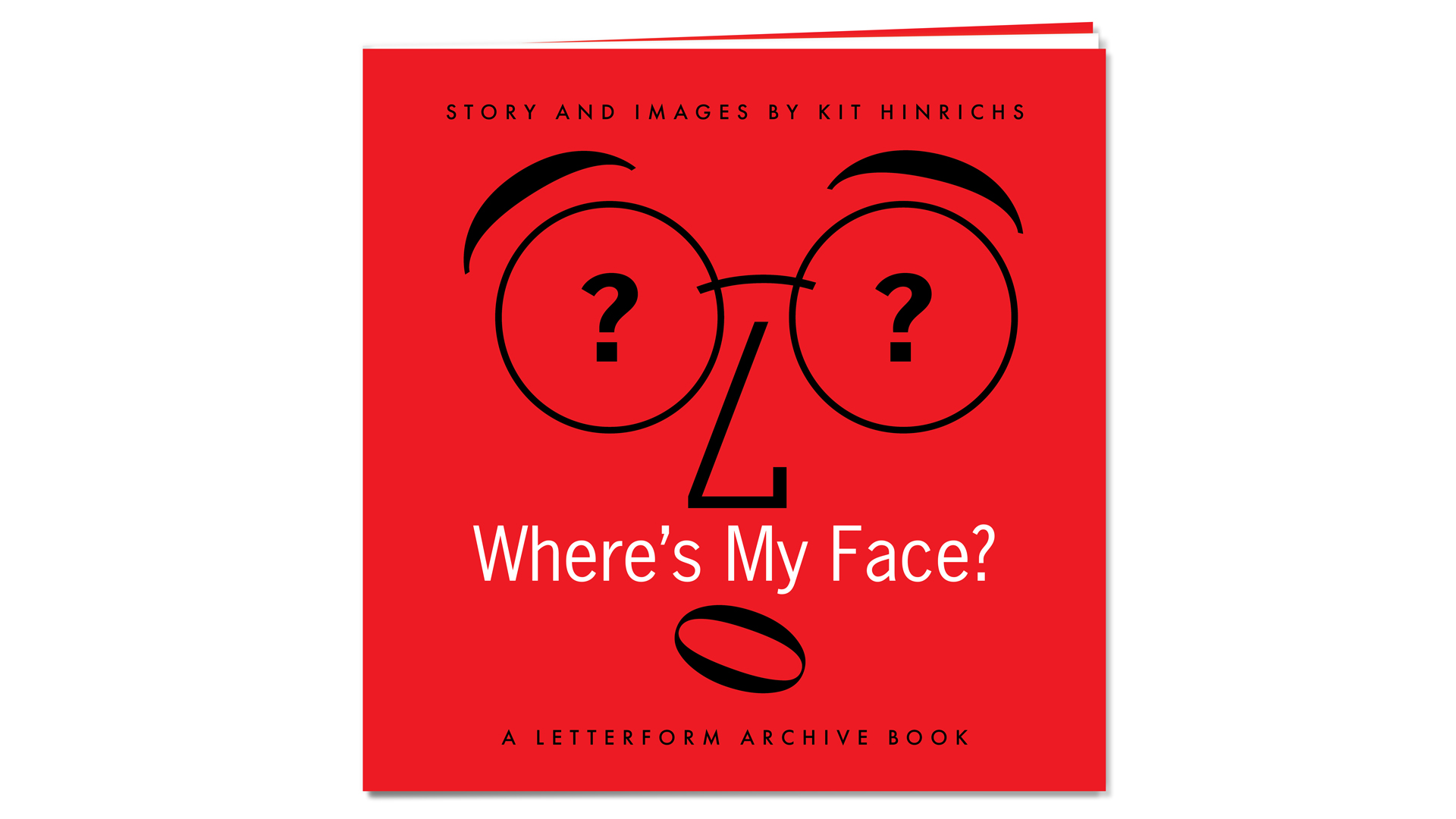

Once that was done, another opportunity has arisen to tell a children's story, and this one is self-generated. [The project is] to tell a children's story through typography and the many, many faces of typography, which are parallel to the many, many faces of mankind. It's a story of trying to look at understand, evaluate people around the world, in this case using the metaphor of typography. Right now I'm going for a grant on it. The book is called Where's My Face? and it's been fun developing it and it will be even more fun as we take it to that next stage.

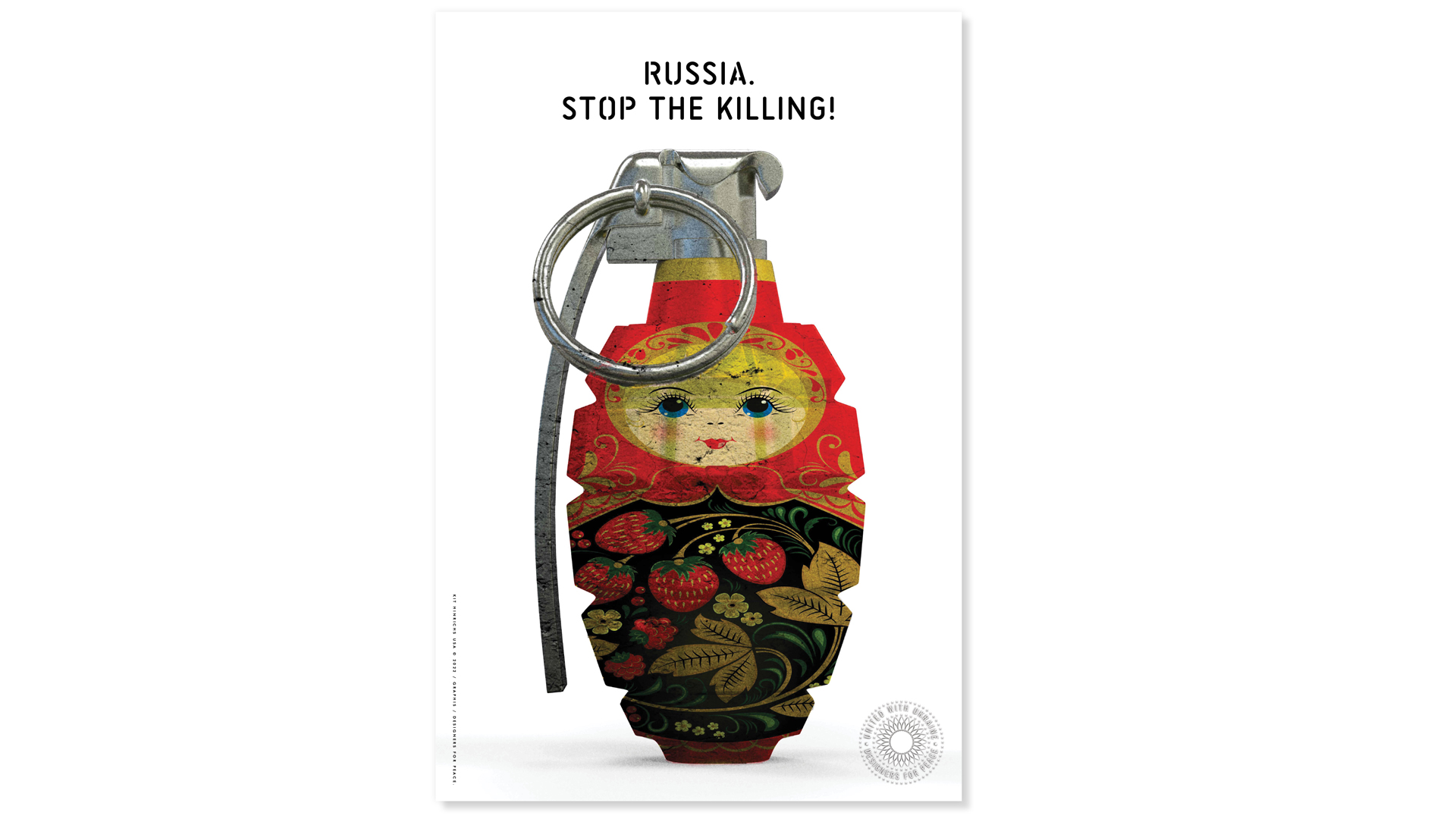

Tell me about the Designers for Peace project

As most of us in the Western world were so shocked by Russia and its incursion into Ukraine, it seemed like there are a lot of things that can be done to support the Ukrainian people. But designers don't always have a lot that they can do. Yes, they can send some money... but we have a great ability to communicate and convince people with our visual art and craft.

I had suggested to Martin Pedersen, the publisher of Graphis, if they would help me put together a program for designers to do posters about about the Ukraine and in support of the Ukraine. And he said, 'it'd be good to have something done for that terrible thing'. So we went ahead and put it together, we had an international call for entries, and we subsequently received entries from over 130 different countries.

Can projects like these ever be enough?

I like to think that it at least reaches out for the Ukrainian people to say, 'yes, we're there'. I think it makes an international cause for the world in general. And I think that ultimately, these things do have impact in changing people's minds. So I feel strongly that there are very important things that we can do.

Tell me about your early days as a designer

I'd worked for a couple of small agencies in New York because I went there after school and then started a small design firm with Tony Russell [Russell & Hinrichs]. I was the illustrator side of the partnership... To differentiate myself... I would illustrate the bills or invoices that I sent to people, so I would sew a felt banner or I would create a puzzle, or I would do a little bit of a sculpture, anything that would help differentiate me from other people out there. People began to notice that, pay attention and I got more assignments and they started to build, and a lot of it had to do with just the creation of these unique bills that they got in addition to the illustration I did for them.

It's just a simple thing. And it does take extra effort, sometimes I put more effort into doing the bills than I did in the job itself – just because the job had been relatively simple. But I wanted people to remember me, and that was a very simple way to do it.

Is that one of your tips for a young designer?

I think the idea [of thinking about] what you could do to differentiate yourself, besides the work you do, is helpful. And this was a different time when you sent physical bills to people. Now everything is so electronic that these opportunities are not quite as easy, but I think if you're creative, you can come up with something that will work for you.

What do you do when you get stuck for ideas?

I'm very much a believer in free association. So I sometimes just let my mind drift. And the nice thing is, as a storyteller, I have usually brought together a number of ideas, and thoughts come from the client or my own research on a particular subject. And when you have all those things to play with, you let your mind kind of float and all of a sudden, it's like a gestation period. These things kind of come together.

I don't normally get stuck, and one of the hard parts of doing this for as long as I have is that you start thinking you've got a solution to everything. And trying to keep the ideas fresh is the really the toughest part at this point in my career.

What do you do to combat that?

I think, 'haven't I used this particular idea before? Haven't I used a solution like this?' I constantly am fighting myself... And when there is something [different], it's a really 'aha' moment and you say, 'wow, that is really different'. That's when I know we're on the right track.

I also look at things around life in general. I look at design annuals, I go to museums. I'm always hopefully aware of what's going on within our culture. And that's always an inspiration for me as well.

What makes Pentagram different from other agencies?

Several things, but one thing is the owners of the company are the designers themselves, the principals are the people who run it and conjure up the direction that the company is going to take. And we're continually... I speak as if I'm still a partner... but we have something called the world's smallest design exhibitions every six months. We teach each other during that period of time. And so we learned from all of our partners... and you get inside information.

And I think this idea that every time a new partner comes in the company in a whole changes to a certain extent, it's an ever changing-organisation, which is why it's kept so fresh after 50 years. It's been amazing. And there's no individual who really drives it, but collectively, the talent involved in it internationally is pretty amazing. I certainly learned from it and I think a good number of designers around the world have been influenced by it and certainly businesses are aware of it as well.

So it's one of those things where so many organisations have been bought by larger organisations who are not really design organisations, but they wanted to put something together with whatever else they're doing in their consulting. And I think it's great that Pentagram is able to maintain its independence, and that's what's kept the ideas fresh.

How did you feel when you left?

You'd like to think that, 'oh they're really gonna have a tough time now that I've left', but I know better than that. It was a wonderful thing to be part of and when I talk to people I use it as a reference point... but it also taught me all kinds of things that allowed me to continue on in my own career, utilising what I learned during this organisation of these fabulous international designers. I still consider them all my friends, we occasionally consult with each other and we talk to each other about what we're doing. It's a great organisation.

Was there anyone you connected with in particular?

Three of us joined at once, so I was either the ninth or the eleventh partner that joined at that time, and now there are over 25 partners, and many have gone in between. Certainly Colin Forbes was very instrumental in bringing me in and directing me as I went from being a design office, but not that big a one, to an international operation. He was instrumental in how I was able to grow... John McConnell was very important to me on the London side.

There are so many partners on the US side... Woody Pirtle was very important to me, Paula Scher of course is just an amazing talent, and Michael Bierut. Although I was a partners before any of those guys happened to join, but nonetheless, l continued to work with them and knew of them before they joined.

What has been the biggest change in the design industry over your career?

I hate to make a piece of technology this important thing, but there's no doubt that the computer has done amazing things, good and bad. The good thing is it allows you to do much more experimentation in a quicker period of time and have access to things all over the world. At the same time, there's always a typeface, there's always spacing, there's always something that the computer has done. And it's a bad crutch. It's pretty easy to say, 'that doesn't look too bad, I guess we'll just use that'.

I happen to be fortunate enough to have come from a sketching everything, drawing everything beforehand [background], and knowing the value of that, and creating ideas to come from that and being able to utilise a computer to expand upon that experience.

What do you think the future of design looks like?

As I've said in the book, I think the future is being written now by the new, next generation of designers. I'm hoping that the work from my generation of designers has helped start that next generation of designers, [enabling them] to explore areas that we were unable to at that point and technology's allowed us to expand upon. And I'm looking forward, and I'm really as interested as anybody else [in finding out] what is going to happen.

Anything else to add?

In very simple terms, I'm fortunate to have been able to make a living doing something that I love. And it's been rewarding to me in all kinds of ways intellectually and financially along the way. But I hope that there's the same kind of enthusiasm in the design work that we do, and the cultural contribution that design makes to our global culture. Because I keep thinking, we can't always just kind of say, 'Is it efficient and is it cheap and can we get it done?' It's just not a criteria for me. It's the value that we created along the way, and I want to be sure that we keep that in mind, because we have a very important role in that as designers.

We need those who are in the field to help shape how that next generation is going to appreciate and understand that. I think it is our role for those who have been in the field for a while to help direct them but not to direct them to make them do what we've done, but to help them understand the value of what we do, and that I think is just by doing.

Narrative Design: A 50 year perspective by Kit Hinrichs is available to pre-order now

Find out more about Kit Hinrichs via the Studio Hinrichs website.

Get the Creative Bloq Newsletter

Daily design news, reviews, how-tos and more, as picked by the editors.

Thank you for reading 5 articles this month* Join now for unlimited access

Enjoy your first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

*Read 5 free articles per month without a subscription

Join now for unlimited access

Try first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

Rosie Hilder is Creative Bloq's Deputy Editor. After beginning her career in journalism in Argentina – where she worked as Deputy Editor of Time Out Buenos Aires – she moved back to the UK and joined Future Plc in 2016. Since then, she's worked as Operations Editor on magazines including Computer Arts, 3D World and Paint & Draw and Mac|Life. In 2018, she joined Creative Bloq, where she now assists with the daily management of the site, including growing the site's reach, getting involved in events, such as judging the Brand Impact Awards, and helping make sure our content serves the reader as best it can.