Brendan Dawes on stories hidden in data

The designer and artist (and disliker of both terms) explains his passion for finding stories hidden in data.

Brendan Dawes will be at Generate London in September. Don't miss his workshop on how data is awesome, or his talk on paper, plastic and pixels; book now!

Flatly, he says: "I'm Brendan Dawes. I design things for a living. I was a director in a design company for ten years. I left them [magneticNorth]; I'm just doing my own thing now." The flatness begins to lift. "It's great," he smiles. "I'm working from home and working for some nice clients." His tone begins to suggest real pleasure. "I wake up every day thinking, 'What can I make today?'"

But what does Dawes actually make?

It seems an obvious question, but by the time we say goodbye, I've come to understand why it's one that he doesn't like. It's not that he's evasive; rather that his take on the obvious is elegantly different.

I'm sure he'll disagree, but Dawes seems to revel in finding delight in the obvious. The obvious is a box waiting to be opened up and its internal quirks revealed. Obvious things like data, for example. As we shall see, he finds some amazing things inside oceans of bland ones and blander noughts.

The archetypal Dawes

For me, if there's one piece that comes close to typifying a 'Brendan Dawes project', it's Whilst I Was Sleeping.

It's a brown paper bag: an obvious and everyday object.

Get the Creative Bloq Newsletter

Daily design news, reviews, how-tos and more, as picked by the editors.

Every week, in the early hours of Sunday morning, ten images printed out from Dawes's Instagram feed are automatically placed in the bag. Each time he wakes, he's delighted by what he finds: delight inside the bland and obvious. The piece also explores the meeting point of the analogue and digital worlds, another recurring motif in his work.

Fending off my attempts to get him to pigeonhole himself as either an artist or a designer, Dawes says: "It's for other people to make those judgements. For me, it's about the work I put out there. I love Thomas Heatherwick, and people are constantly trying to describe who he is. One minute, he's an architect; the next, he's an engineer, an artist, a designer … people say he's a Renaissance man, but he's defined by the work he's done."

"His book [Making] is full of failed projects, project that didn't win pitches. Even at his level, he's still pitching. I've just read René Redzepi's book [A Work in Progress] too. He's a chef at Noma, in Denmark. He's working like a dog; he's never satisfied; he's constantly thinking of new ways to do things. I'm not a cook but I'm fascinated by the creative process within anyone. I respect that love of craft."

Spielberg vs Kubrick

So when did Dawes discover art? "I failed art at school," he says. "I [left] when I was 16 and have never had any formal training. I'm writing the foreword to an art school's book at the minute. The original title was 'Why should you go to art school?'"

Summing up his take on art, Dawes cites Terry Gilliam. "He said he admires Spielberg and Kubrick but, for him, Spielberg is all about giving you answers where Kubrick is all about asking questions. For me, that's the difference between art and design. Design is all about answers and art is about questions. I think, with the work I do, l lean more toward asking questions. But the guy who looks after my work at the [Richard Goodall] gallery in Manchester insists I call myself an artist as it helps sell the work better." He laughs.

How did technology first appear in his life? "My Grandad bought me a ZX81," he says. "I remember plugging it into the TV in his lounge and it blew me away. The idea that I could write things and they would appear on the telly just connected with me. I was always into my Atari VCS, but this was a way to do my own stuff."

After Sinclair’s little black box, Dawes moved onto the Atari ST. "It had a MIDI port, which was a pretty strange business decision, but the ST became the machine of music." he recalls. That musical dalliance turned into a serious romance, and Dawes later began a sound engineering course.

Mining data for deaths

His training in sound engineering still influences the work he does today, or at least the metaphors he uses to describe it. To make many of his pieces, Dawes takes data sets and presents them in unexpected ways. "With data, there's often a lot of noise, so it's about the stuff you leave out," he says. "There's a lot of filtering to be done on the data I use."

Dawes says that he regards this process as similar to that of shaping a story. "[For me, data is] more than just ones and noughts," he explains. "It's a cast of characters for which I create a script."

By way of illustration, he points to his James Bond Kills piece. Created to celebrate the fiftieth anniversary of Dr. No, it shows the number of bad guys Bond offs in the course of each movie, based on data provided by The Guardian. "It was a throwaway thing that went around the internet for a day," he says. "But the story that came out of that was that Bond killed 47 people in GoldenEye but only one in The Man With The Golden Gun. The data was all there in the CSV file, but if you use graphic design you can surface that in a very simplistic way. [It] was the story that people picked up on."

Nature's mathematics

We move on to discuss Dawes’s EE – Digital City Portraits project in which he took data from the mobile phone operator and turned it into portraits of 11 UK cities, using the same mathematics that defines the form of the head of a sunflower. Explaining the piece, he says: "With everything I do, I want an emotional reaction. I don't want people to go, 'Yeah, that's all right.' I want it to be visceral."

"When I showed the client, they loved it, which is great. But the piece was also for an audience. We'd go round all these different cities and do civic receptions showing the work. The mayors would be there and [while they certainly weren't] into data visualisation, their responses were genuine. They understood it and they started to have conversations around the data. And this is the whole point."

Data you can trip over

"I've described data as snow, falling all around us," Dawes says. "You can pick it up and shape into different forms. That's why I'm interested in creating 3D models out of it. What happens when you can hold data in your hand? What happens when you can bump into data and trip over it?"

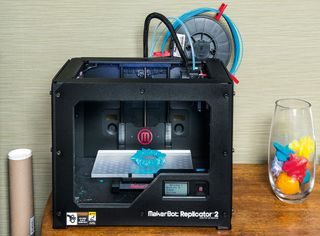

To help his audience do just that, Dawes uses a 3D printer. But despite his enthusiasm for its practical applications, he remains sceptical of the current hype surrounding 3D printing. "I can now write a piece of software and have the data print out. I couldn't do that before. But, you know, there [are a lot of myths] about how everyone is going to own a 3D printer and how we're going to be printing god-knows-what in our own homes."

By way of analogy, he points to tailoring. "Everyone can learn to sew, but it's easier and cheaper to nip down the shop."

"3D printing is an amazing technology and it's getting better all the time ... but we're making lots of landfill," he continues. "That's all right [when] you're learning to use [new technology], but [an artist's] job is to apply some good taste. That's what I'm trying to do. I'm not making egg cups any more. My wife doesn't want nuclear green egg cups in the kitchen."

Making memory tangible

Dawes is also unconvinced by technology's determination to make yesterday's products obsolete. "I still use Dieter Rams' calculator. It's over 40 years old, it's beautiful and I use it every day, even though I've got a calculator on my phone. I've also got a Bang & Olufsen amplifier that was made in 1965. When I listen to Spotify, it goes through this 50-year-old piece of kit! It still sounds amazing."

"It's the same thing with apps. There's this idea that if you're not updating an app, it's obsolete. People say, 'It looks like development on this is dead'. But what happens if version one was right? There isn't a version two of the Mona Lisa. [Leonardo da Vinci] probably went through iterations, but he didn't do Mona Lisa 2.0."

We move on to discuss Object For The Display Of Memories, which encloses a USB memory stick in a clear plastic hemisphere that holds objects that provide clues to the nature of the data it contains. Is it a comment on the transiency of digital information?

"In a way, digital is less transient," he replies. "You can archive it. It isn't like pieces of paper that are going to disintegrate; you don't have to look after it and keep it out of the sun. Yet it still feels transient." The confusion arises because digital information is intangible, he points out. "People want to do more with their hands. It makes them feel more connected to the creative process. When you're working on a screen all day with a mouse, there's a disconnect there. That's why you get people like me obsessing about pencils. Maybe the iPad is better, because you touch stuff. But the iPad feels like a consumer's product, not a creator's product."

No comment: Just work

And what of the internet? Is that a consumer's or a creator's medium? "I get a bit pissed off with the web," Dawes says. "Twitter seems to be full of people telling other people what to do. I'm sick of people saying what makes good design when they've never designed anything in their lives."

But before I can ask him if he's ever tempted to go on Twitter himself to set the record straight, Dawes makes a comment that returns us to the start of the interview, and his reluctance to provide a neat, reductive soundbite to describe what it is that he does. "I don't write articles about design," he says. "I make my comments through the work. I prefer it that way."

Don't miss Brendan's workshop and talk at Generate London, 21-23 September. To find out more about what's on there and at other conferences, head straight to the Generate site.

This article was originally published in net magazine issue 255. Subscribe today!

Thank you for reading 5 articles this month* Join now for unlimited access

Enjoy your first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

*Read 5 free articles per month without a subscription

Join now for unlimited access

Try first month for just £1 / $1 / €1