Bjork artist shares his techniques and inspirations

We chat to leading Icelandic artist Thrandur Thorarinsson about mastering perspective and mixing fantasy and reality.

The wind is more than bracing as it blasts in from the north, scouring the streets of Reykjavik and leaving them covered in a thin layer of ice. The gale is so strong that Thrandur Thorarinsson has trouble pushing the door open to let us into his studio on Skulagata, which faces right onto the cold and angry sea. With the wind chill, it feels like minus 10.

“Come in, come in,” he says warmly, with a faint grin that lets you know this is all normal in Iceland. “Do you want a coffee?”

Coffee in his studio sounds like the best offer in the world. There are canvases everywhere, many of them semi-complete, and immediately it’s clear how much draughtsmanship goes into one of his pieces. On one, there’s just a rough grid he uses to block in the composition. Others have monochrome shades painted in, with faint lines running to the horizon as he works out the perspective, paying particular attention to the architecture.

“I recommend standing if you can and having a lot of space so you can step back and see what you’re doing at a distance,” Thorarinsson advises. “Even if you’re working on a small painting I find it extremely useful to see the painting at a distance. The longer the distance the better.”

A change of scenery

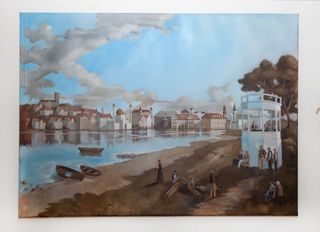

Though he’s too humble to admit it, Thorarinsson is one of Iceland’s national painters. He’s popular with the country’s biggest names: rock band Sigur Ros owns one of his pieces, and last year he painted a portrait of Bjork. The country and its capital are two of his favourite topics. Look closely at his beautiful Reykjavik landscapes, however, and you’ll notice there’s usually something a little different about them.

“There are some charming streets and neighbourhoods here, but there’s always some modern and ugly architecture I find that spoils it a bit, so I thought I’d paint Reykjavik and take out all the buildings that I dislike and put in something pretty instead,” he explains.

On the main square, for instance, stands the old parliament building – solid stone, traditional. There’s Hotel Borg, an elegant Art Deco creation, as well as a lovely church and some other 19th century structures. And yet in amongst them is a 60s piece that Thorarinsson considers hideous. “I just put a building in there that matched the others, with a tower on top,” he says.

Get the Creative Bloq Newsletter

Daily design news, reviews, how-tos and more, as picked by the editors.

The 1990s town hall is a modern building with a concrete structure, glass curtain walls and a cantilever roof. But in Thorarinsson’s Reykjavik, it doesn’t exist – he’s replaced it with a North African mosque. For him brash modern buildings don’t fit, and neither does the idea of paving over a lovely old canal.

“In my painting there’s a canal instead of a road. There was a very small canal there but it can’t be seen today. I opened it up like a Dutch-looking canal and that’s actually an idea that’s been tossed around quite a bit, that we should open up this,” he explains.

Old masters

In fact, there is a touch of Dutch in many of his works. Thorarinsson paints exclusively in oils, in the style of the old masters. Rembrandt and Rubens are two he refers to, as well as some of the Italian masters. One of his favourite techniques is gleaned from da Vinci himself: “Use a mirror,” he says. “I do it quite a lot. Just a hand mirror like this is quite convenient, just to look at the work and a reflection of it.”

Born in Akureyri in northern Iceland, Thorarinsson is half-Norwegian. Growing up he spent time in both countries, and took art through his school years. He then attended the Iceland Academy of Arts. However, because he wanted to paint like an old master, and the school focuses on more modernist styles, they parted company after a year. Instead, he trained as an apprentice to the Norwegian painter Odd Nerdrum who, at the time, had his studio in Reykjavik. Thorarinsson literally approached him in a café one day, and the rest is history.

Social commentary

Thorarinsson recently studied philosophy in Copenhagen, and will be holding a major exhibition there in 2018. Similar to his Reykjavik paintings, for his Copenhagen show he’s re-imagining the Christiania precinct of the Danish capital. It’s an anarchist commune that was declared in 1971, and has been controversial ever since. On the one hand, residents lead an idealistic lifestyle, on the other there’s a street devoted to cannabis products.

One of Thorarinsson’s paintings is of Pusher Street. Another features some policemen tipping their hats to residents from a Christiania bicycle, a type of bike invented in the area.

“I’m not making a gritty social realist commentary,” says Thorarinsson. “It’s not a documentary at all. I try to idolise it a bit because it is quite a charming place, and also because all the local architecture there is very beautiful. It’s just 19th century buildings, and older, like military buildings that have been decorated quite vividly. Lovely surroundings. I try to just bring out the best of it.”

In the meantime, his Reykjavik paintings continue. In progress is a piece commenting on how the city has become a tourist mecca. It’s inspired by Hitchcock’s The Birds, but instead of terrifying crows there are puffins.

“There’s been an explosion of tourism in the last few years which is very good, it has a very good effect on the economy of the country but it also has the effect that in downtown Reykjavik there’s only tourist stores now,” says Thorarinsson. “The puffin’s sort of become a shorthand for tourists here in Iceland. But just a few years ago the puffin was not a bird that Icelanders identified with. Now it’s become very much a symbol for Iceland.”

Grit and gore

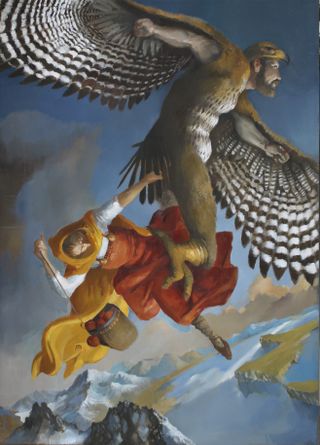

If puffins on the attack isn’t terrifying enough for you, then Thorarinsson is happy to oblige with some even darker works. He’s using his old masterly skills to depict some of Iceland’s folklore and its history. Some of it is rational and sedate, like the enlightened gents who proved that Mount Hekla is not a gateway to hell. Some of it is beautiful and poetic, such as his painting of a winged giant kidnapping Idunn, keeper of the apples of youth. But some of it is quite horrific.

One of Thorarinsson’s most popular paintings is also one of his most terrifying. His painting Grýla depicts a witch from Icelandic folklore literally eating a child in his bed. It was shared on Reddit and through it Thorarinsson found a worldwide audience.

“There are quite a few drawings and depictions of her but they’re usually caricatures of her carrying a bag. I thought I should make a really scary picture of Grylla, something that could scare people even today,” he says.

In the same way that he uses his old masterly style to give Reykjavik the buildings it deserves, Thorarinsson is doing the same for Icelandic folklore. When the Renaissance painters were depicting stories from ancient Greece and Rome, Iceland didn’t have any painters to revive its classical mythology.

“I thought that it would be nice to do Rubin-esque paintings but with subjects from the sagas,” says Thorarinsson. “I thought that would be a nice combination. I just swapped the Greek mythology with the Norse. I find that they translate easily into paintings and they also have this connection with the old masters who painted quite early.”

Related articles:

Thank you for reading 5 articles this month* Join now for unlimited access

Enjoy your first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

*Read 5 free articles per month without a subscription

Join now for unlimited access

Try first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

Garrick Webster is a freelance copywriter and branding specialist. He’s worked with major renewable energy companies such as Ecotricity and the Green Britain Group, and has helped develop award-winning branding and packaging for several distilleries in the UK, the US and Australia. He’s a former editor of Computer Arts magazine and has been writing about design, creativity and technology since 1995.