Behind the scenes of Peter Rabbit

How the much-loved bunny was brought to the big screen.

Will Gluck’s Peter Rabbit, based on the characters created by Beatrix Potter, is the latest in a line of 3D movies to go the way of the CG/live-action hybrid. But just what is involved in making a film where most of your characters need to be added later? How do you plan, how do you shoot with live-action actors, and where do you start with animation?

Animation and visual effects studio Animal Logic was responsible for many of Peter Rabbit's VFX shots, from planning the shoot, to filming with stand-ins, building a whole raft of adorable CG characters and then animating them. It’s a lot more work than you might think, and Animal Logic’s animated feature pipeline – recently boosted from its growing work on recent Lego-related films – came in incredibly handy.

Planning for Peter

Peter Rabbit tells the story of a group of rabbits and other animals who think they have overcome the dreaded Mr. McGregor (Sam Neill), only to find a new member of the McGregor family (Domhnall Gleeson) has taken up residence instead, and has become interested in their animal-loving friend Bea (Rose Byrne).

Incorporating this ensemble of human actors was one of the first big challenges faced by the filmmakers, since the actors would regularly be interacting with Peter (voiced by James Corden) and his furry friends. Interestingly, Gluck mostly eschewed any kind of previs for planning out scenes. Instead, the film was heavily storyboarded and, once shot, the director had artists do storyboarded draw-overs of the planned CG characters into his edit.

That didn’t mean scenes were not planned out during shooting, especially where significant rabbit and human interaction was necessary. Here, Animal Logic visual effects supervisor Will Reichelt worked closely with the stunts team and the actors to choreograph the action, sometimes with bluescreened performers pushing around sticks or stand-ins on set in Sydney, Australia and for some filming in the UK. One scene even includes a whole lot of fisticuffs between Peter and Gleeson’s Thomas McGregor.

“Domhnall was very much up for anything physical and threw himself right into it,” says Reichelt. “It really makes the sequence because you can see the effort and exertion. It really makes you feel like Peter’s kicks and punches are actually landing, and that’s even without having a guy in a blue suit shoving a stick in his face.”

Shooting for real

That brings us to the next big challenge: making sure the CG characters could be lit and integrated realistically into the live action scenes. That involved a significant level of skill from the visual effects team, but they were aided by the use of a proprietary on-set HDRI system for obtaining high-quality and largely automated image-based lighting data. The system used Indiecam’s nakedEYE VR camera.

Get the Creative Bloq Newsletter

Daily design news, reviews, how-tos and more, as picked by the editors.

“The camera is designed to shoot 4K video, but we got them to reprogram it, to shoot HDRs,” explains Reichelt. “The idea was to try to come up with a system that was going to be less of a footprint, both physically and time-wise on set, but still give us what we needed. You would plonk it down, step away, and hit a button on an iPad and it would just capture all of the exposures that you need in basically 15 seconds as opposed to someone running in with a DSLR.

“We were also able to set the height super low to the ground – about six inches off the ground – which meant we were able to capture something that was more accurate to where it needed to be in order to light the rabbits correctly,” adds Reichelt. “We could get it into little, tiny crevasses, like in the garden and wherever it needed to be, and not have to worry that we had some whopping great tripod with a DSLR on it.”

Making rabbits

After the shoot, Animal Logic embarked on the weighty task of animating the rabbits, as well as several other animals including a fox, pig, hedgehog and even a rooster (which just happens to be voiced by Reichelt). A major effort became ‘finding’ the characters, especially since they were animals with human traits. Artists had to work out whether the animals would remain quadrupeds or bipedal and how much range of emotion to give them.

“Very early on we played with the idea of doing runs and walks as bipeds,” notes Animal Logic animation supervisor Simon Pickard. “And on the live action plates it just looked wrong, so in the film they very rarely walk or run on two legs. Whenever they need to get from A to B, we drop them into quads, and they become more realistic and more like real animals. Then they come back up, and start acting again.

“We also started doing tests with very restrained facial animation,” continues Pickard. “Then, as the film opened up, we realised that we were probably going to have to push away from that a little bit more, and try and find this blend. James Corden, especially, has got so much energy and zest in his voice that the restrained kind of facial acting didn’t quite marry with his voice, so we started pushing a little bit more on the facial side. And it was finding that balance.”

Animators studied hundreds of hours of rabbit reference, picking through footage to find little nuances, ear flicks and ticks that were layered into the animation. “Some things were actually too much, though,” says Pickard, “Like nose twitches, for example. If you look at a rabbit, it never stops twitching its nose. What we found was, when we started animating a performance like that, it just got distracting, and quite annoying. You were constantly looking at this nose twitching away, rather than getting into the subtleties of the facial animation.”

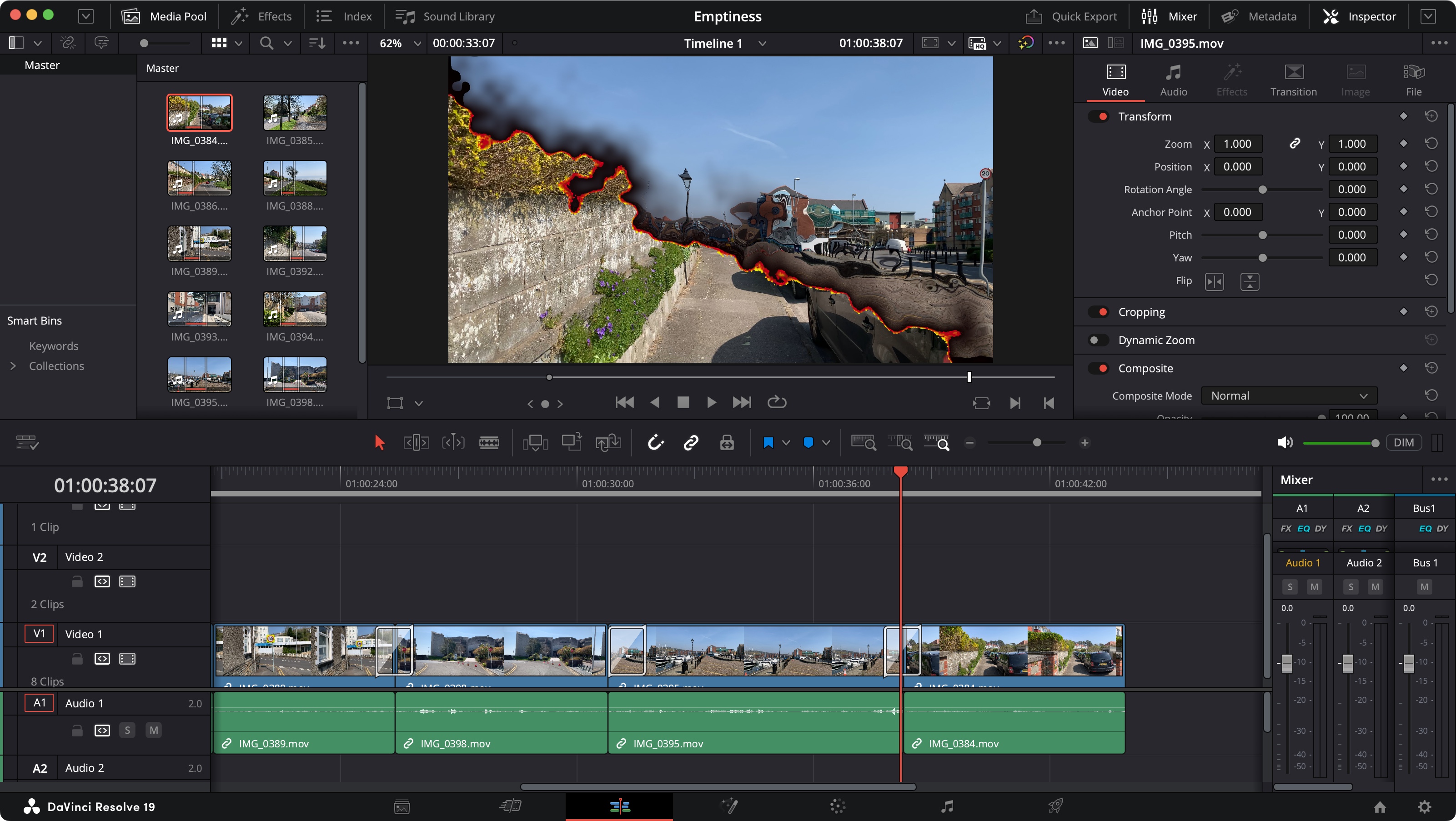

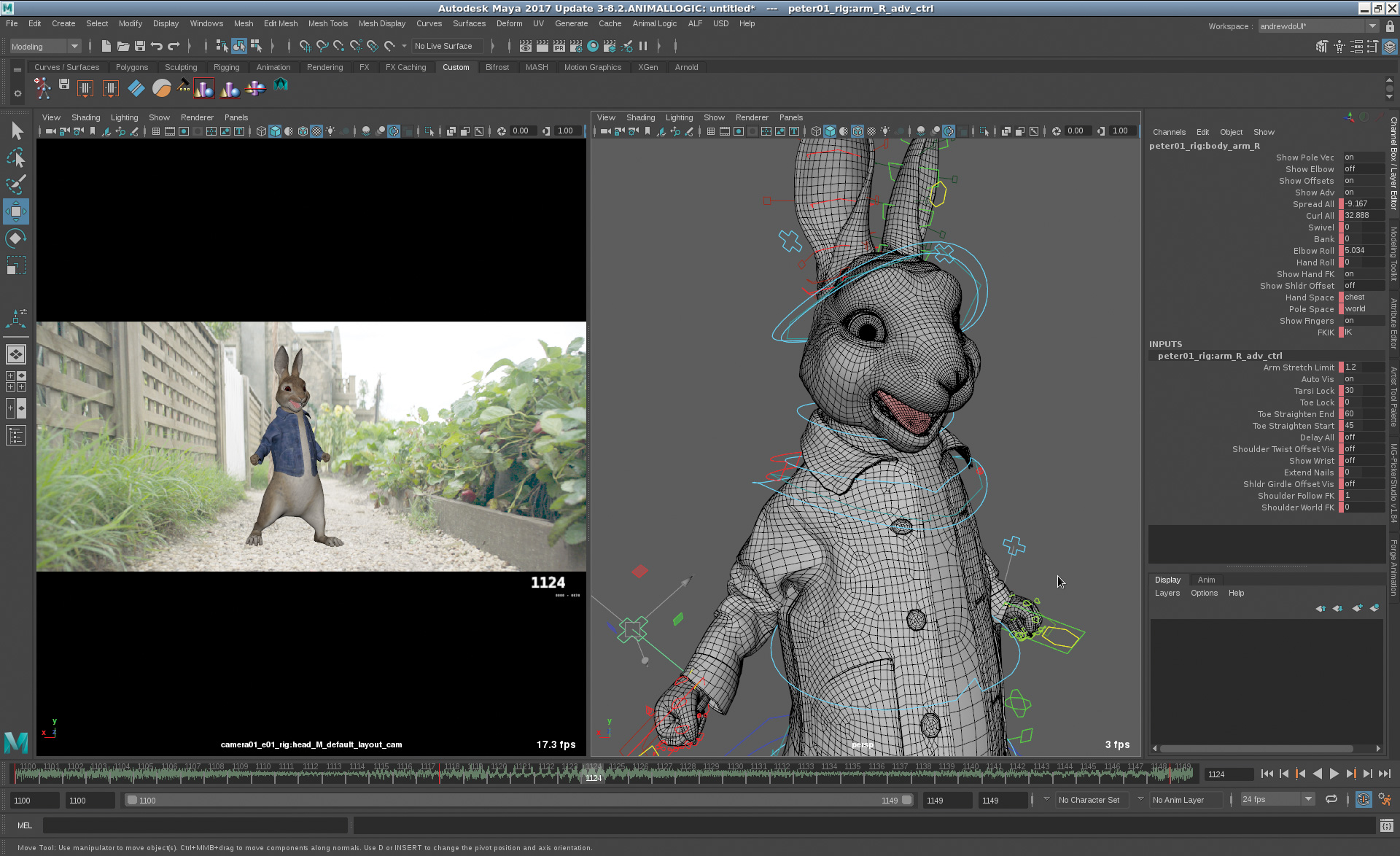

Peter Rabbit was Animal Logic’s first project moving over from a Softimage XSI pipeline to Autodesk Maya. The animation team also took advantage of improvements made to the studio’s ‘Renderboy’ tool, which automates renders designed for reviews. Since many of the CG characters would be furred creatures, animators in the past have found it difficult to animate them and see the final results – “expressions can get lost by the time you render,” comments Pickard.

But Renderboy provided the animators with quick visual feedback by showing the characters with fur, cloth, motion blur and image-based lighting, during the animation process without having to wait for a final render. “It was a game-changer for this project,” says Pickard. “The only issue was that they were so good it confused people at times, as they thought they were looking at a final-quality render.”

The final look of fur for the CG characters, along with dynamic clothing made with a tool called Weave, remained a significant challenge for Animal Logic. In recent times, starting with The Lego Movie, the studio has built and maintained its own inhouse path trace renderer called Glimpse. That work continued on Peter Rabbit, with Glimpse upgraded to enable physically plausible rendering of hair and fur via Animal Logic’s proprietary grooming tool known as Alfro.

“Not only did we use it to create fur for the characters, but we also used it to create big swatches of CG grass as well,” details Reichelt. “There is a lot of digital grass in the film because we needed it to integrate the characters into the ground, for a start. There were also large swatches of the set that had been trampled too much and that had gone to a muddy sort of bog, which didn’t quite look like the beautiful, lush Lake District it was supposed to.”

Bringing it all together

Both Reichelt and Pickard nominate that fight scene between Peter and Thomas McGregor as the toughest of the film, but also the most pointed in showcasing the collaboration between all departments – from on-set shooting to animation and right through to the final rendering and compositing.

Each shot in the scene was often filmed two to three times, once with ‘stuffies’ as stand-ins for Peter, then sometimes with a person off-camera prodding Gleeson with a stick to deform his skin or clothing as if Peter was pushing against him, and again with no stand-ins for a ‘clean plate’.

I was in the director’s tent so I could actually see what the shot would look like,” says Pickard. “It would be like, ‘Is that good? Did we get it?’ Sometimes you’d have to say no, and it was 50 people having to reset the shot for an invisible rabbit they couldn’t see at that point.”

“It’s a massive amount of work even just to rotomate the humans, because you need to know what they’re doing in 3D space before you can even animate to it, and you have to get detailed right down to the finger joints,” adds Reichelt.

“Those shots are absolutely brutal. If Domhnall’s throwing Peter up against a wall, you really want to feel like his hand is fully pressing into him and the fur is coming up around the fingers. It was a complicated back and forth from everybody, but I’m really happy with the way it turned out.”

This article originally appeared in 3D World issue 233; subscribe here.

Related articles:

Thank you for reading 5 articles this month* Join now for unlimited access

Enjoy your first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

*Read 5 free articles per month without a subscription

Join now for unlimited access

Try first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

Ian Failes is a VFX journalist, who has written for a number of creative titles, including fxguide, Cartoon Brew, VFX Voice, 3D Artist, 3D World, Thrillist, Syfy, Inverse, Digital Arts, MovieMaker, Empire Magazine Australia, Develop, Rolling Stone and Polygon. Ian now runs befores & afters, a brand-new visual effects and animation online magazine.