5 key trends in character design

Five exciting directions in contemporary character design.

Contemporary character design is both exciting and ever-evolving. As technology advances and becomes ever more complex, designers are using these advances to go in the opposite direction – playing with their characters in ways that are perhaps simpler and more child-like than in the past.

New technologies are shaping the way that characters are created, and the way they interact with audiences. And as we become increasingly obsessed with our own image, tweaking the way our own ‘character’ or self is portrayed online, artists are reimagining faces and expressions in innovative ways.

Read on to discover more about how modern life is shaping character design, and sometimes, vice versa, with these five exciting character design trends.

01. Viral design

Not so much a design trend as an 'audience trend', more so than ever before, the characters we design do not belong to their creators. As they become charged with our projection, imagination, fantasy and longing, they gain a virtual identity or life of their own, making them independent from their creators.

This has arguably always been true, but the internet has increased the speed of their diffusion. Characters now act as autonomous agents, roaming freely across media, spreading like wildfire across social networks and attaching themselves to other artefacts beyond our control.

One character that has taken on a life of its own is Edel Rodriguez’s illustration of Donald Trump, which has been featured on many magazine covers, from Time to Der Spiegel, and has been appropriated by many people at political demonstrations.

Rodriguez has made this Trump icon his signature, constantly recombining the colours and elements, and his viral work draws on other trends in illustration, with an eschewing of realistic depictions in favour of typographic and symbolic abstractions.

Get the Creative Bloq Newsletter

Daily design news, reviews, how-tos and more, as picked by the editors.

Another example embodying these issues is Sean Charmatz’s Secret World of Stuff. Charmatz creates characters by using Photoshop to add simple lines to his photos of found objects, such as egg boxes, pizza, leaves and bin bags.

He has a huge following on Instagram and his work is often shared without proper credit – a big issue for artists today.

The reason for his viral success probably lies less in the character design itself, but in the work’s ability to tell simple short stories in one image. There are silly stories, but also images related to friendship, family, death or loneliness.

This emphasis on storytelling is present in many fields, from branding to interface design, and makes this an exciting time for designers and their characters.

02. Illustrating with 3D shapes

In many cases, character design is about breaking down shapes into geometrical forms. This is one of the fundamental rules of animation production, and has been essential for enabling international teams to work on the same thing in different places.

Currently playing with such geometrical elements for character design in an inspiring way are 3D artists. In sharp contrast to the hyper-realistic simulation that has long been dominant in 3D, artists can have fun experimenting with a simple way of juggling geometrical forms to create pleasing new characters.

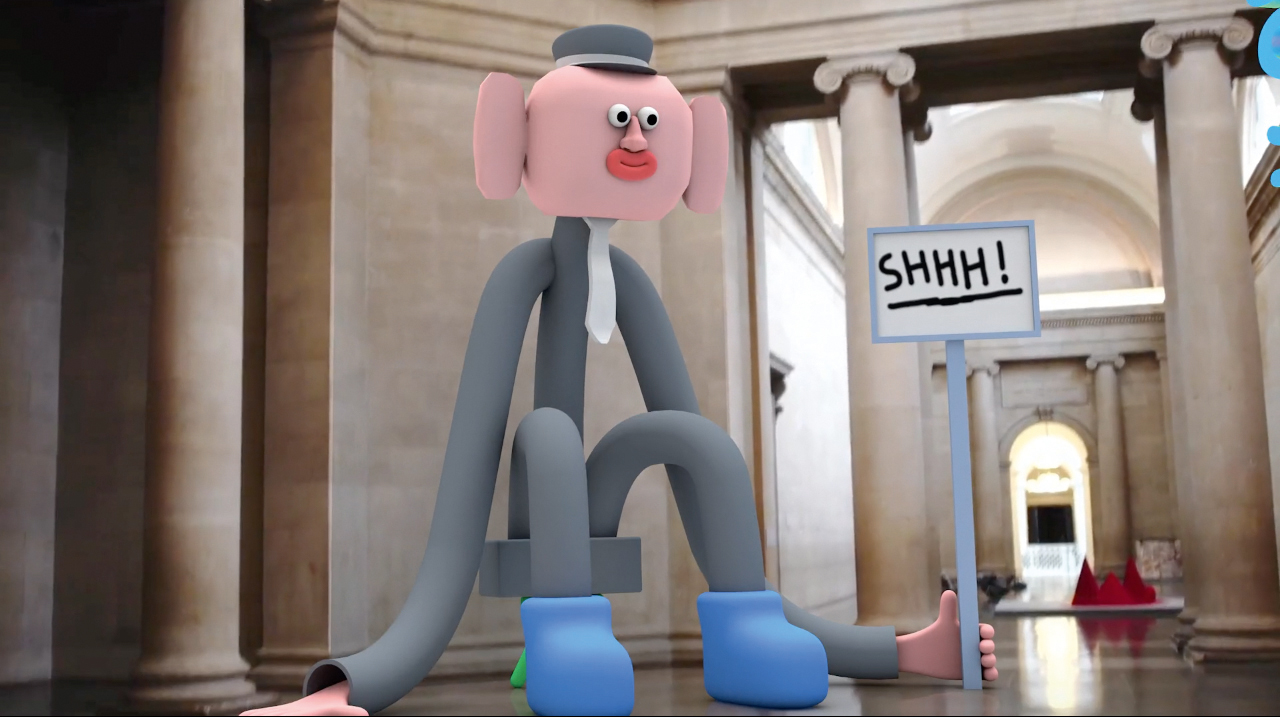

Jack Sachs, who recently moved from London to Berlin, works as animator and illustrator. He studied illustration at Camberwell College of Arts, but while recovering from a hand injury, he had to take a break from traditional drawing and started making 3D work on the computer.

These two practices have fused to become the work he makes today: jumbled up faces, bright colours, and lumpy shapes, inspired by the pioneers of early CGI. His 3D renders are often consciously misplaced into live action video footage, with characters emerging from a solid floor, as in his recent work SHHH! for Tate Britain (above).

Cecy Meade from Monterrey, Mexico, has a similar approach – exposing the geometric configuration of 3D modelling.

Her works often depict characters head-on and in a less dynamic way than Sachs – leading to a direct confrontation with the viewer. Like many 3D illustrators, she constructs her work based on hand-drawn sketches, which she then reconfigures in geometrical elements.

Julian Glander, from New York, works in various genres including comics, video games, short films and illustration. He never sketches, but combines simple geometric shapes straight in the free and open-source 3D software Blender.

His pastel toned yet vibrant Florida-inspired colour palette stands in contrast to the often violent and dystopian undertones of his work.

03. New expressions in selfie culture

We live in times of photographic terror. Our smartphones, the internet and the speed of data means we are constantly producing and reproducing our visual identity through selfies, and playing with it through face-swapping apps, Instagram and Snapchat filters.

This selfie cult has sparked various artistic reactions. Artists and designers have come up with creative alternatives to reinvent facial representation.

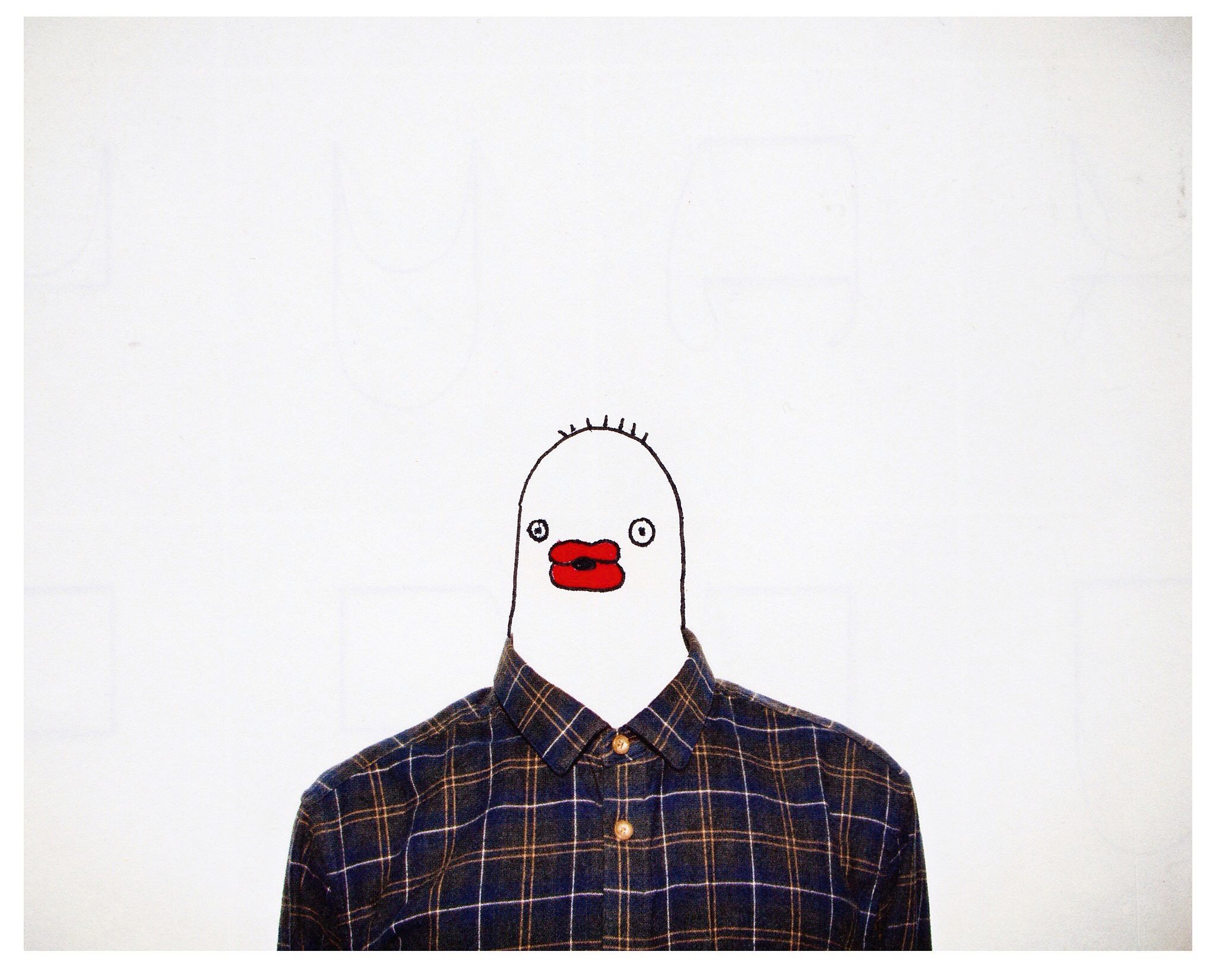

Italian artist Fabio Tonetto began digitally overlaying heads in photos a few years ago, while Paris-based Geneviève Gauckler has long been experimenting with the combination of mundane photorealistic objects and graphical identities.

Gauckler's artwork replaces the head in photos with simple geometric shapes and combines elements to form new faces.

Her work is all about nostalgia for mundane everyday objects and her love for the absurd. The simplicity of her character design emotes the feeling of being a spectator, an outsider looking at things as if for the first time.

Guillaume Kashima is a French-Japanese illustrator living in Berlin. His style is minimalist yet bold – he works mainly with black and white, plus strong, primary colours to create simple facial designs for a range of contexts.

Recently, he has started to experiment with classical portraits, giving them warped facial features, multiple eyes and thoughtful poses.

His Classics series of Risograph prints subvert traditional ideas and artwork by inserting playful images, such as fed up-looking naked woman farting, on classical vases.

After quitting her job in a branding agency, Ton Mak from Shanghai decided to fully concentrate on what she had been unconsciously doing most of the time – doodling.

Within a short time, she simplified her style to create the expanding Flabjacks universe, a lumpy, chubby species differentiated through hairstyles, clothes and props. Their curious, ambiguous faces are a vehicle for the artist to reflect on her own identity. She also experiments with photomontage, which she bases on portraits of herself and her family.

04. Interactive characters

In 1994, Karl Sims, computer graphic artist and MIT researcher, released Evolved Virtual Creatures – animated videos showing creatures that had been tested to see whether they could perform a given task, such as swimming or jumping, and then evolved accordingly.

They reacted to their environment and interacted with the others, similar to characters in a game. This ground-breaking work is still influential today.

Eran Hilleli, an animation filmmaker from Israel, is currently expanding his work in this direction. He is renowned for his geometric style and mysterious characters created with cinematic flair.

In addition to animated shorts, music videos and adverts, he experiments with GIF loops, such as a group of characters around a camp fire or some ethereal-looking vegetation moving in the wind.

For his animated trailer for the Style Frames conference, he first tested the walking cycles of his characters constructed of geometric shapes to see if they felt organic. From this exploration, he put together his cast of eclectic characters for the parade featured in the animation.

Hilleli’s latest exploration Character Synth is an interactive installation, in which a male character is portrayed on a computer screen.

Visitors can sit at the desk to interact with the character through a midi controller, which operates oscillating sine waves and random noise and results in the character deforming as if injecting waves into its bones.

By combining different commands through the midi, players can observe endless different ways of transformation, meaning that Character Synth is a system that can be stimulated and interacted with, rather than a linear animation with different options that tell a story.

Another animation artist expanding his practice is Mate Steinforth, creative director at Berlin studio Sehsucht. His Instagram feed is an exploration of the behaviour of detached parts in a hyperrealist rendered setting – hands float through the air, geometric forms bounce at each other, a face is a Tinder screen to swipe through.

These clips are neither interactive, nor based on a program within a system. Rather they seem to be experiments of Technoself Studies – singling out specific contexts of our cultures and letting them spin in autonomous loops.

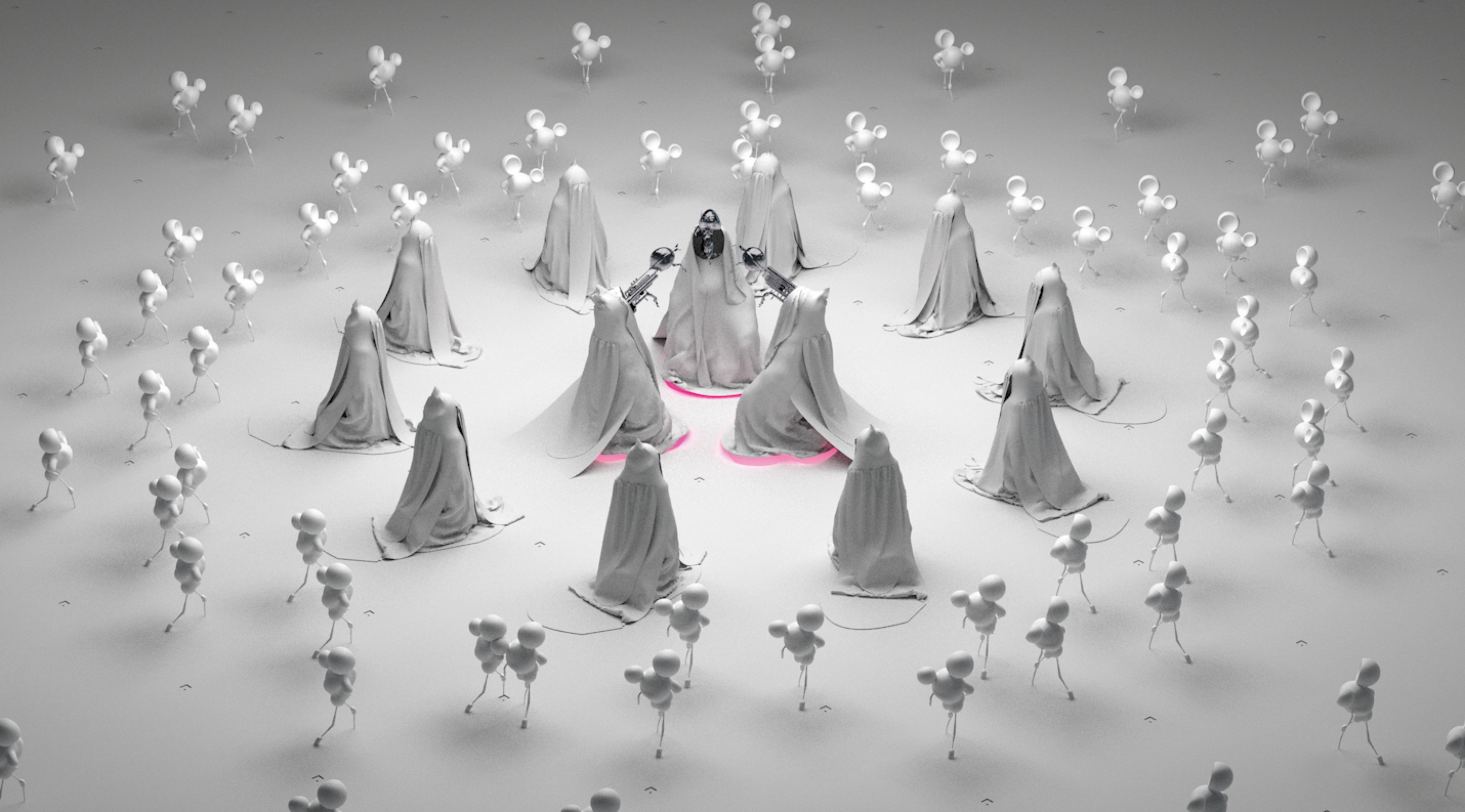

Based on such experiments, Steinforth worked on the animated trailer for 2017's Pictoplasma Conference. He created a cast of occult monks and allowed them to move through void 3D environments. Following this research of the behaviour and movement of his characters, he created the final animation.

Seoul-based animation director and media artist Jun seo Hahm adds a biological perspective to this type of research, replacing real creatures in the natural world with artificial ones in a CG environment.

He examines the behaviour of simple forms and how their movement is based on their restrictions, and his film project Walking Follows Form is a stunning expression of how a character’s body structure informs its style of walking.

05. Breaking the rules of gaming

From Space Invaders to Super Mario, early computer games have been key to defining the aesthetics of contemporary character design. Games have the potential to develop a character-driven narrative, in particular when the design defines the characters’ abilities to move and act within the designated world.

Mainstream titles have tended to design characters to fulfil a function in a given story, but within the current movement of indie games, it is character design that is at the forefront of the development process. There is also increasingly room for plots that are not about winning but exploring.

Currently under development, Pikuniku breaks the traditional rules of gaming. It is a “therapeutic playground where the player will need to think creatively.”

There are no enemies to fight or kill, the avatar is not a hero, and, most importantly, you cannot die. The character is a red, oval shape with just two eyes and thin, long, waggly legs, and its mission is to rebuild a community.

The character’s design is also key – it was the starting point for the game. One of the two creators, Rémi Forcadell, had animated a short clip of its movement, and when Arnaud De Bock saw the short GIF online, he contacted him and proposed working on a game together.

Pikuniku has not only maintained the character’s oddness but bases everything on it. It moves through the game seeming helpless at first, but learns to act socially through encountering other creatures that require its assistance.

In a similar tone, Ooblets is also about creating social coherence through farming little creatures, the Ooblets. Though it’s much more refined and polished in its look than Pikuniku, Ooblets also began with design rather than concept.

The promotion of Ooblets has also been outside of traditional norms, as creators Rebecca Cordingley and Ben Wasser have been actively promoting the game’s characters and scenes online in order to build a fan base before the release – hopefully later this year.

Award-winning puzzle game GNOG is about exploring virtual toys, and has the option to play in VR via PlayStation VR. The player has to experiment with a new GNOG head in each level – by pushing and pulling different levers or rotating the head, for example – to uncover its secrets.

Its lead designer, Samuel Boucher of Montreal-based KO_OP studio, has a passion for experimenting with facial designs, and it shows.

In GNOG, the character’s vibrant face is the environment – it’s a facial machine to operate and to play with. Once again, there are no winners or losers as such, making the experience more akin to child’s play than is traditional in gaming.

This article originally featured in a 2017 issue of Computer Arts magazine. Subscribe here.

Read more:

Thank you for reading 5 articles this month* Join now for unlimited access

Enjoy your first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

*Read 5 free articles per month without a subscription

Join now for unlimited access

Try first month for just £1 / $1 / €1