Tortured artists: do you suffer for your art?

Do demons kindle creativity? We invite experts into the world of the tortured commercial artist.

The Madness of Hugo Van Der Goes depicts its subject wide-eyed, dishevelled, with one hand clawing at the other. The artist is sat in the monastery where he sought refuge from his demons.

Van Der Goes – at the time, dean of the painters' guild in Ghent, Belgium – entered Roode Kloster in 1475. Here he suffered a mental breakdown, attempted suicide and died seven years later.

Win clients & work smarter with our FREE ebook: get it now!

He continued to paint throughout this time, but was said to be dissatisfied with his work – the story that's told in Emile Wauters' 19th-century painting.

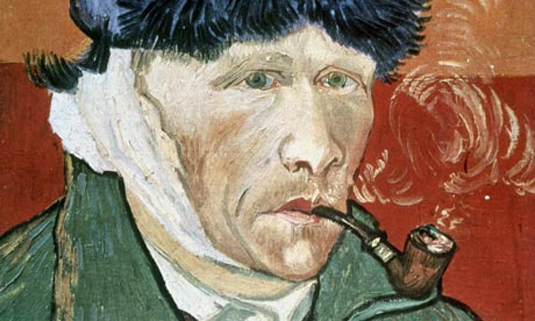

Vincent Van Gogh wrote in a July 1888 letter to brother Theo: "I am not ill, but without the slightest doubt I'd get that way if I don't eat well and if I don't stop painting for a few days. As a matter of fact, I'm again pretty nearly reduced to the madness of Hugo Van Der Goes in Wauters' painting."

It was not the only time the Dutch artist compared himself to Van Der Goes.

Art critic Jonathan Jones describes Van Gogh – who, missing much of an ear and after a stint in an asylum, is believed to have shot himself and died from his injuries in 1890 – as being "fascinated, and perhaps inspired by, the story of this medieval artist's madness"."

Get the Creative Bloq Newsletter

Daily design news, reviews, how-tos and more, as picked by the editors.

The most famous of tortured artists, it seems, was himself captivated by a tortured artist. Should we be surprised if the rest of the art world has followed suit?

"There's some romanticising that goes on about the tortured artist," says Weta Workshop artist Greg Broadmore, "but generally that idea doesn't hold as much water in the world of art for entertainment." While sceptical of such notions, he admits his job can be an "emotional rollercoaster".

Artists almost need to have certain qualities that verge on mental illness

"Your art is you, no matter what the subject, and so to put it out there can make you feel vulnerable. We put great pressures on ourselves.

"Often I'm frustrated or even depressed by my work. I just want it to be better; it's never as good as I want it to be. I don't share that feeling externally very often, so it can weigh me down."

The idea of the tortured artist took root with the Romantics in the early part of the 19th century.

Romanticism, which valued subjectivity and individualism above all else, saw madness as a kind of elevated state – a place to unlock hidden genius and uncover profound truths. The madman was someone who adventured into the unknown, the insane artist held up as a hero.

If the tortures of the soul keep someone from producing work, obviously, that's not much help

But long before the Romantics, Plato planted the seeds of this idea. The philosopher suggested madness was a "gift of heaven", something which "comes from God, whereas sober sense is merely human".

Join the dots between Plato, the Romantic Movement and Van Gogh and you can see how the idea of the tortured artist has grown into the intractable myth it is today.

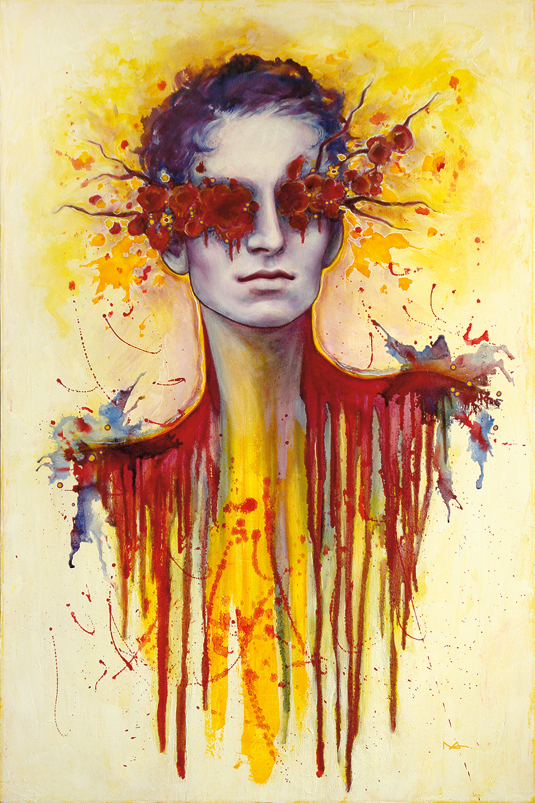

Nykolai Aleksander – a self-confessed Leonardo da Vinci addict who knows her art history – says, in the past, the artist was a craftsman who didn't enjoy the same social status as is afforded them now.

They laboured under pressure – tight budgets, expensive materials, tough working conditions – while commissions and censorship dictated what they could and couldn't paint.

"All in all this hasn't changed that much," Nykolai says. "Many artists continue to fight making a living from their work, and many of the traditional mediums still pose a serious mental health risk."

The German Stellar Art Award-winner stresses there's nothing romantic or glamorous about real mental illness, and working artists today don't have time to pretend otherwise.

"It's hard to keep up with workloads and deadlines – something as simple as a cold or flu could upset schedules. Clients expect you to do the work when they need it to be done. If you can't, they'll simply ask someone more reliable."

But are artistic endeavours any more stressful than other professions?

A study published in the Journal of Psychiatric Research used Swedish health records to identify over a million people diagnosed with various mental illnesses.

Researchers compared these 'cases' to those from a matched group without psychiatric diagnoses.

The study measured the amount of people within each group who had, or recently had, creative occupations. The study found that, overall, people in creative professions were no more likely to suffer from a psychiatric disorder than those in the matched group. In fact, people with creative jobs were significantly less likely to be diagnosed with many forms of mental illness.

The study, while not without its flaws, seems to dispel the myth of the tortured artist. However, lead researcher Dr Simon Kyaga said the findings also suggested certain disorders, which were no more likely to occur in creative people, may actually have a positive effect on creativity.

"Artists almost need to have certain qualities that verge on mental illness," James Gurney says, "such as obsession, deeply felt emotion, social alienation, and an odd mix of egoism and self-doubt."

Californian artist James is best known for illustrated book series Dinotopia and a string of best-selling art theory books. He says playing up to the role may have been beneficial for the Romantics in separating what they did from the carpenter, the blacksmith. But he prefers to think of art as a cure for, rather than the cause of, certain troubles.

There are serious misunderstandings about creativity and mental health that can be dangerous to people

"The idea of the struggling, tortured, mad genius is a legacy of the Romantic period, and it makes great copy for art historians. But some of that is PR on the part of the artists, and some of it comes from the fanciful notions that grew up long after the facts. But if the tortures of the soul keep someone from producing work, obviously, that's not much help.

"Think Winsor McCay, Arthur Rackham and Milt Kahl: all great artists with bizarre imaginations, who were as reliable and workmanlike as watchmakers."

Next page: Find out what expert Dr Richards says on creativity and health...

Thank you for reading 5 articles this month* Join now for unlimited access

Enjoy your first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

*Read 5 free articles per month without a subscription

Join now for unlimited access

Try first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

The Creative Bloq team is made up of a group of art and design enthusiasts, and has changed and evolved since Creative Bloq began back in 2012. The current website team consists of eight full-time members of staff: Editor Georgia Coggan, Deputy Editor Rosie Hilder, Ecommerce Editor Beren Neale, Senior News Editor Daniel Piper, Editor, Digital Art and 3D Ian Dean, Tech Reviews Editor Erlingur Einarsson, Ecommerce Writer Beth Nicholls and Staff Writer Natalie Fear, as well as a roster of freelancers from around the world. The ImagineFX magazine team also pitch in, ensuring that content from leading digital art publication ImagineFX is represented on Creative Bloq.