Type on the web

Advances in online standards mean that print and web design are beginning to converge. Jim McCauley speaks to five designers bringing print sensibilities onto the screen

The problem that’s dogged web design ever since there’s been a web to design for is that you rarely get exactly what you want. With print design, things tend to be relatively straightforward: you design something, and that’s what appears in print. Simple.

Whereas web design is much more dynamic and, let’s be honest, more troublesome. The most telling weakness in web design, historically, has been typography. Proper typography simply hasn’t been feasible on a platform like the World Wide Web, and instead designers have had to stick to a narrow range of typefaces that users are most likely to have installed, with the most basic of controls over how they’re displayed on-screen.

Thankfully matters are beginning to change. Developments in web standards mean that web designers are able to wield ever-increasing amounts of control over the final look of a site, and without having to resort to Flash or, in worst case scenarios, designing in Photoshop and slapping the resulting image online.

Best of all, web designers can now specify the exact font that will be displayed on their sites. Firstly through sIFR, and now Web Open Font Format, designers are able to pick and choose from a broad range of fonts in much the same way as they would for print. It’s still far from perfect; says Dan Rose, graphic designer and creator of the Photoshop Etiquette Manifesto for Web Designers: “It’s surprisingly difficult, but the web has made great strides to make type easier. The reasons are two-fold: availability and performance. Higher quality fonts should become more available, with Hoefler & Frere-Jones about to offer their collection for the web. Even with the flux of webfont services, sub-par hinting and smoothing on Windows can make some fonts unusable.”

With CSS3 designers can exert much more control over how typography looks online. In fact, we’ve almost reached the point where print design skills are becoming a positive boon in designing for online, instead of something to try and forget so as to avoid disappointment.

Ryan Scherf, a designer from Minneapolis, agrees. “I’ve seen many websites in the last year that remind me more of a magazine layout, and less of a standard web layout,” he says. “By applying print design skills on the web, the possibilities are essentially endless.”

The new site he’s designed for Bloom Health reflects the increased amounts of control he has at his disposal. “I started out by designing the main tag line: ‘Our Help. Your Benefit’. Bloom had already come up with the tagline, and there was a muted colour palette in place. The rest of the design really built from that. I wanted to take the layout from a traditional company website to something more modern. I knew I loved the inset look – wrapping features and images with a little darker border to essentially ‘frame them up’ – so I tried to incorporate that as much as possible in the design. I think this type of inset gives a designer the depth into the screen that is necessary, as most of the typography appears to be popping off the screen.”

The typography’s also enhanced by Scherf’s combination of the cursive Metroscript with the big and bold League Gothic. “The idea to pair the two together kind of came randomly. I was walking around downtown Minneapolis and I saw a soft script paired with bold letters and I felt that was the exact combination I wanted to see. There was something elegant and unique about pairing two completely different fonts together. I couldn’t be happier with it.”

The end result went down well with the client. “The best feedback I’ve heard was from the CEO,” recalls Scherf. “After he approved, he said, ‘This is like nothing else I’ve ever seen,’ which felt really great. It’s fun to know that you’ve managed to create something truly unique in the days of themes and templates.”

For Octopress, a static site blogging framework designed for hackers, Brandon Mathis wanted to use freely available web fonts and opted for Google’s web fonts directory, which he describes as the simplest way to use free fonts online. “Google hosts the files and handles delivering the right formats based on the capabilities of each browser,” says Mathis. “After trying out several different fonts, I chose PT Serif for headings and paragraph text, and PT Sans for navigation, sidebar sections and various other parts of the site. I opted for them because they both come in families of four (normal, bold, italic, and bold italic), have a nice restrained character, and are specifically designed for screen readability.”

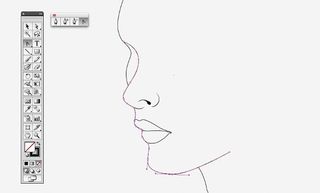

Rather than reach for Photoshop Mathis designed entirely in a web browser, writing HTML and initially working without background colours and images so as to develop a typography-focused design. “After I had something that worked, I studied the ‘320 and Up’ approach to media queries which I then immediately fell in love with, and rewrote my layout code to incorporate what I’d learned. I searched the web for the latest and best information I could find on semantic HTML5, and improved my mark-up, adding some publishing micro formats as well. At one point I stumbled upon this wonderful article on semantic pull quotes and I worked it into my design.”

Mathis’s code-based approach might be a terrifying prospect for the average designer, but this is how you integrate the really clever stuff into your design before everyone else. Being able to get down and dirty with the code is also a brilliant tool for any web designer, and Mathis has been grateful for the new techniques he’s picked up on this project. He says: “Working on Octopress has been an opportunity for me to experiment with new technology and pursue excellence beyond the scope of my design consulting work.”

When 8faces.com, the web presence of Elliot Jay Stocks’ typography magazine, needed a redesign, it fell to Kyle Meyer, including the serious business of choosing and implementing the typography. “The primary typeface is FF Meta Serif, which had been slated for use in the magazine by Stocks,” says Meyer. “Thankfully Typekit had just started offering the typeface, albeit in limited weights, during our design phase. Lucida Grande was added for extra clarity in small type situations and to create a pleasing sans/serif contrast. It also added a dash of friendliness thanks to its relatively large x-height.”

Not only did the typography prove painless, Meyer also found that the whole site design process went pleasingly smoothly. “Working with Stocks was wonderful,” he recalls. “I was able to go from sketched wireframes into design quite quickly, thanks to his own design foresight. There were a few iterations in Photoshop each time. The latest update was meant to be minor, but I had a happy accident in Photoshop by mistakenly transforming the background colour in the masthead to a larger size. A bit of tweaking and a go ahead from Stocks and we ended up having a moderately scoped redesign.”

Meyer was fortunate to have a client, and indeed a project, that was all about the fonts. However, he notes that this isn’t always the case. “Explaining the benefits of webfonts can be difficult to clients, especially in situations where you have recurring billing on an annual or monthly basis. Clients often have a tough time grasping aspects of accessibility compliance and the benefits webfonts provide in this area.”

Rose feels that even now, clients often expect a finished site to look exactly like the Photoshop mock-ups, and still need the difference between print and online explained to them. “The difference is in the medium,” he points out. “The printed page is a set format, giving you total control of how type looks, bleeds, and relates to other elements. With the web, there are so many variables between device width, readability, and browser rendering that you need to negotiate. It’s our job to educate clients and help them feel comfortable with the concept that type won’t look exactly the same in different browsers or platforms.”

Mike Kus, who has recently drawn acclaim for the new site he designed for Amazee Labs, is more circumspect about client expectations. “There are very few things that you can’t achieve on the web that you can in print,” he says. “I don’t think most clients know the difference, and I don’t think it matters; they just want to see great results, and it’s our job to deliver them.”

For the Amazee site, Kus worked from wireframes that the Amazee team had put together. “They were more of a content guide,” he notes. “I wasn’t expected to follow them from a layout perspective – Amazee gave me total creative freedom.

“I started with the homepage. I tried to come up with something that explained what they did visually with an accompanying strapline. I was also very conscious of producing a visual design that expressed the fun and creative personality of Amazee Labs. I came up with the ‘making your web work’ strapline and the lightbulb illustration containing the hand drawn, web development related words. This became a solid foundation on which to build.”

As for the font, Kus hunted around the web until he found Kyle Steed’s ‘Clumsy’ font and realised that it was perfect for the site. The end result is a design that’s surprised Kus with its widespread popularity. “I’ve had amazing feedback,” he says. “A lot more than I expected, to be honest – the design to me was a logical solution to the problem. That’s the way I generally approach my design work. I just try to answer the brief in the best and most appropriate way I can.”

With print increasingly feeling the pinch, there’s no better time for designers to at least get a feel for how to unleash their talents online. Meyer sees things less in terms of print design versus web design, and more as design in general. “It’s about a person’s overall design abilities,” he concludes. “A good eye for visual hierarchy, a solid understanding of working with type, and a bit of creative wit are universal and cross over to interactive design immediately.”

Get the Creative Bloq Newsletter

Daily design news, reviews, how-tos and more, as picked by the editors.

Thank you for reading 5 articles this month* Join now for unlimited access

Enjoy your first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

*Read 5 free articles per month without a subscription

Join now for unlimited access

Try first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

The Creative Bloq team is made up of a group of design fans, and has changed and evolved since Creative Bloq began back in 2012. The current website team consists of eight full-time members of staff: Editor Georgia Coggan, Deputy Editor Rosie Hilder, Ecommerce Editor Beren Neale, Senior News Editor Daniel Piper, Editor, Digital Art and 3D Ian Dean, Tech Reviews Editor Erlingur Einarsson and Ecommerce Writer Beth Nicholls and Staff Writer Natalie Fear, as well as a roster of freelancers from around the world. The 3D World and ImagineFX magazine teams also pitch in, ensuring that content from 3D World and ImagineFX is represented on Creative Bloq.