Owen Gildersleeve: Paper cuts

In a world dominated largely by digital design, Owen Gildersleeve’s joyous papercraft creations hark back to an age of hand-crafted labours of love

Having graduated just four years ago, Owen Gildersleeve can already boast a considerable reputation as a master of papercraft and other handmade work. His bright, clean and playful images for the likes of Wired, the Guardian, Rolex and Cadbury celebrate the childhood pleasures of making complex objects from nothing more than coloured card – or, at least, that’s how his expertise make them appear.

So it’s surprising, perhaps, that this softly-spoken, highly articulate 26-year-old didn’t start his career intending to work solely in the field for which he’s now become known. “I suppose that it’s more the enjoyment of making stuff by hand, and that has gradually moved into papercraft, quite organically,” explains Gildersleeve.

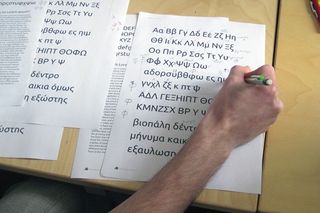

While he was still studying graphic design, Gildersleeve co-founded a collective called Evening Tweed, and through that began to create a lot of handmade type for various freelance projects. “As time went on, and people wanted more imagery and less type in illustrations, I tried to find a good medium to use that was still tactile but would allow me a bit more freedom,” he says. “Now it’s got to the stage where most of the work I do is paper-based. It was quite a natural thing. Having said that, I’m still trying to do other things in the handmade realm, not just paper work.”

When we talk, Gildersleeve is busy chasing costings for a new commission from Global Blue, the international shopping company, as well as finishing off a couple of other projects. Does he prefer having several jobs on the go? “Well, I like to be able to do one job at a time, but it never really works out that way,” he laughs.

“Last week, for instance, I had three projects with deadlines and I was trying to work on all of them. And then some weeks you have a quiet patch. A lot of the things I get offered are quite exciting, so it’s nice to take on as much as I can and get involved in stuff.”

Gildersleeve’s work process is dominated by planning, as you might expect from such a physically orientated craft. “Once you start making, it’s harder to implement big changes, so it’s nice to know that once scalpel goes to paper, things are signed off – even little details such as colour choice,” he says. “I tend to do lots of mock-ups, with lots of to-ing and fro-ing with the client, making sure everyone’s happy – so that when I make it I know there won’t be too many changes. Of course, there always are.”

In terms of design, he generally sketches by hand, scans his drawings into Photoshop and composites from there, or uses Illustrator to create a drawing. “In fact,” he explains, “more and more I’m using Illustrator because I can get the type looking exactly as I want, or I can combine hand-drawn typography with some vector elements,” .

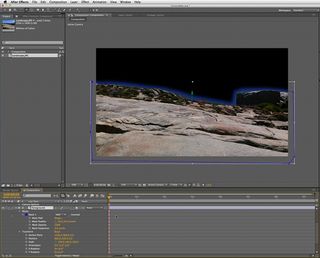

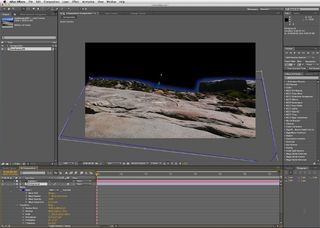

Either way, he then prints out the finished design to begin cutting out by hand, as he does with all his papercraft projects. “They’re printed backwards so that when I cut them out the lines aren’t visible because they’re on the back of the design,” he says. When projects are shot by him or his collaborators, rather than the client, he will also retouch the resulting images, sometimes heavily. “So the digital side does play a big part in every project,” he adds. “It’s the middle bit, the cutting-out, where I try to get away from the computer for a while.”

As complex as many of Gildersleeve’s designs can look in a finished image, their construction can be even more fiendishly cunning – shored up with shortcuts and temporary workarounds that can’t be seen from that fixed viewpoint. One such commission was from the Royal Mail for last year’s annual stamp album, with a chapter celebrating the work of William Morris. Gildersleeve designed the chapter page title illustration: “It involved lots of very detailed typography, all cut out by hand. That was a complex piece to put together because it was very fiddly and took a long time, creating William Morris patterns with a few of my own.”

In a completely different vein, a more recent project for fashion company Motilo called on his organisational skills. “They’d approached a photographer friend of mine, Ryan Hopkinson, to see if he could make a film showing how to use their website to shop together with a friend,” he explains. “Ryan had the idea of recreating the site as a full-size set, using actual models. That was particularly complex because I had to design the set using some very detailed scale drawings to ensure that when it was blown up, the type was exactly the right size.”

Together with another friend who specialises in woodwork and design, Gildersleeve designed and built the set, and hired two ballet dancers as the anonymous actors, “which meant hair and make-up and so on,” he says. “The other thing that made it complicated is that Ryan insisted we shoot it all in one take. The whole set breaks apart, and things move apart and are put back. In fact we only just got a finished take right at the end of the day.”

Projects such as these, which have pushed his skills in unexpected directions, seem to energise Gildersleeve – particularly moving image work, which he’s determined to explore further. “The thing is, everything I make actually exists [as a physical object],” he reflects. “Having that in a photograph is very nice, but I’m realising more and more that these elements can be moved about and turned into an animation, for example. It’s just nice to see them being brought to life.”

Collaboration is another aspect of his work that Gildersleeve is keen to develop; as projects and commissions become larger, he can call on his network of friends and colleagues to help out, particularly with time-consuming areas such as photography. He’s also excited about exhibiting his work on a larger scale, and now tries, as much as possible, to ensure the finished work can be re-used after a shoot.

In fact, the sky seems to be the limit for Gildersleeve at the moment. There’s just one small problem: space, or the lack of it. “I work in a shared studio and I already feel guilty about the amount of space I take up with my stuff,” he grins. “The guys I share with are lovely and allow me to create a bit of a mess... But I don’t want to start taking the piss!”

Thank you for reading 5 articles this month* Join now for unlimited access

Enjoy your first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

*Read 5 free articles per month without a subscription

Join now for unlimited access

Try first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

Get the Creative Bloq Newsletter

Daily design news, reviews, how-tos and more, as picked by the editors.

The Creative Bloq team is made up of a group of design fans, and has changed and evolved since Creative Bloq began back in 2012. The current website team consists of eight full-time members of staff: Editor Georgia Coggan, Deputy Editor Rosie Hilder, Ecommerce Editor Beren Neale, Senior News Editor Daniel Piper, Editor, Digital Art and 3D Ian Dean, Tech Reviews Editor Erlingur Einarsson and Ecommerce Writer Beth Nicholls and Staff Writer Natalie Fear, as well as a roster of freelancers from around the world. The 3D World and ImagineFX magazine teams also pitch in, ensuring that content from 3D World and ImagineFX is represented on Creative Bloq.