The making of Monument Valley

A surreal journey through fantastical architecture and impossible geometry, ustwogames' Monument Valley treads the line between game and interactive art.

Monument Valley was created by a team at ustwogames, led by Ken Wong. Inspired by the art of MC Escher, Japanese prints and minimalist 3D design, each level in the game is a hand-crafted combination of puzzle, graphic design and architecture. Players guide princess Ida through mysterious monuments, uncovering hidden paths, taking advantage of optical illusions and outsmarting the enigmatic Crow People. Here Ken Wong talks us through the game's creation.

Every project I've worked on has been different, but I always try to make my work, or the work of my team, innovative and full of character. The idea for Monument Valley came out of a brainstorming session a year ago. I've always wanted to make a game about architecture, and during these sessions I came across Ascending and Descending by MC Escher. That gave me the idea for guiding a character from the bottom of a building to the top. At the beginning of the project there was nothing that we sought to achieve other than to create the best game we possibly could.

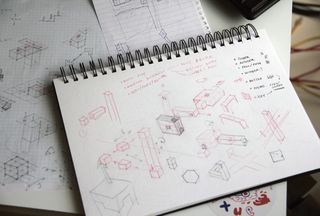

Work in progress

Because Monument Valley doesn't fit easily into an existing genre, we couldn't rely on existing tropes and patterns. We wanted non-gamers to be able to enjoy playing it without help, so we had to study how people interact with the screen, how to maintain their attention and how to curb frustration.

Monument Valley was created using the Unity3D engine. It enabled us to build a working prototype very quickly, and for the artists to be very hands-on. It also enabled us to publish to different platforms relatively simply. It was important to us that the game editor be very flexible, so artists and level designers could iterate quickly and easily.

However, leaving the game levels in this state would have resulted in a slow or choppy experience once on an iPhone or iPad. To remedy this, we had to create systems and adjust code and art to convert our creator-friendly levels into device-optimised levels.

We used Blender for 3D modelling and animation, and Photoshop combined with TexturePacker to create texture atlases. Sound and music were created in Cubase and Vegas, and were then implemented in Unity using a plugin called Fabric.

We set up our art pipeline so that we could make tweaks easily. The colour palette of each level is something that evolved very organically. We printed out every screen of the game and pasted them all on a wall so we could see the game as a colour script, and made modifications based on that. Our shaders system enabled us to apply colour directly instead of creating a true lighting system.

Get the Creative Bloq Newsletter

Daily design news, reviews, how-tos and more, as picked by the editors.

From the beginning we used the gesture of tapping on the path to move the character, and we initially created primitive versions of the two main forms of interactive architecture (the 'draggers' and 'rotators'). We also had early versions of pressure switches and doorways. However, touch controls can be very ambiguous, especially when rotating 3D objects using 2D gestures. We found that everybody touches the screen slightly differently. Lots of programming effort as well as supportive visual treatment went into making these inputs feel responsive and intuitive.

For the sound, we assembled a playlist of music that we thought would fit the game, often combining folk instruments from around the world with electronica. Initially we thought the architecture would have a very realistic sound. However, grinding stone turned out to be quite grating on the ears, as well as being difficult to implement on iPhone speakers.

The game made much more sense once we'd added musical tones to accompany the buildings' movements, giving them a synaesthetic quality that matches the artwork. With the player's interactions now having a musical effect, the soundtrack came to serve as a bed of ambience, inspired largely by Brian Eno.

Conclusion

Apple awarded Monument Valley Editor's Choice in our release week, which helped it become the number one selling app in over 30 countries. We received high scores from the traditional gamer press as well as warm praise from the mainstream press, including the Wall Street Journal and Huffington Post. We've had many touching notes over Twitter from people who see Monument Valley as a work of art. For many it's the first game they've ever completed, and lots of people sent photos of their children or older parents playing it.

We planned from the beginning to make a game where every screen could be framed and hung on a wall. There is very little marketing imagery that isn't playable in the game. In this way, the visuals of the game itself became our strongest asset.

Words: Ken Wong

A member of the ustwogames team, Ken was the designer and lead artist on Monument Valley. An Australian living in London, his previous work includes the art direction of alike: Madness Returns and his solo indie project, Hackycat. This article originally appeared in Computer Arts issue 228.

Thank you for reading 5 articles this month* Join now for unlimited access

Enjoy your first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

*Read 5 free articles per month without a subscription

Join now for unlimited access

Try first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

The Creative Bloq team is made up of a group of design fans, and has changed and evolved since Creative Bloq began back in 2012. The current website team consists of eight full-time members of staff: Editor Georgia Coggan, Deputy Editor Rosie Hilder, Ecommerce Editor Beren Neale, Senior News Editor Daniel Piper, Editor, Digital Art and 3D Ian Dean, Tech Reviews Editor Erlingur Einarsson and Ecommerce Writer Beth Nicholls and Staff Writer Natalie Fear, as well as a roster of freelancers from around the world. The 3D World and ImagineFX magazine teams also pitch in, ensuring that content from 3D World and ImagineFX is represented on Creative Bloq.