Enterprising illustrators explain how (and why) to diversify

Meet an exciting new breed of creatives who are busy diversifying not only to survive, but thrive.

Chances are that if you create illustrations for a living, you also have to be a pretty enterprising character to survive. Unless you're regularly commissioned to sketch front-row at Paris Fashion Week or the phone is ringing off the hook with offers of Sony record sleeves, you have patches of being a bit hard-up.

The good news is that, while there are ever more people in the field, the doors are open for you to create your own chances, rather than wait for that call from your agent. Your horizons as an illustrator are now glitteringly broad.

The meteoric success of the Pick Me Up exhibition at Somerset House over the past four years shows what a multifarious beast the pursuit of illustration can be: from selling products to running workshops. Being an illustrator can, if you choose to embrace it, present far more freedom than responding to client briefs. But how easy is it to make all that energy spent away from actually illustrating things pay? You probably need more than an Etsy shop and the odd exhibition to reap financial rewards from self-initiated work.

Nonetheless, there's a shift in the landscape of illustration that is partly down to the enterprising and entrepreneurial spirit of its practitioners making things to sell, setting up printing presses and publishers, exhibiting, staging events and opening shops - illustrators are creating their own markets.

Alex Spiro of indie publisher Nobrow also makes a connection between economic recession and new technology - a perfect storm for entrepreneurs. "I think people are more critical of who they work for these days," he says, "and perhaps more people feel as though being entrepreneurial is less scary than it was before, because big businesses seem so fragile. Advances in technology have served to lessen the gaps between producers and consumers. I think this has also contributed a lot to the trend."

The move away from homogenised consumption means consumers don't want the high street's identikit offerings, but a more engaging experience of shopping - the thrill of finding something unusual, limited-edition or with an interesting story is more gratifying than quick-fix spending. The internet and social media have liberated enterprising people in every field to access audiences, but the can-do attitude and DIY spirit of illustrators seems to have them particularly well placed to take advantage of these new opportunities.

Channelling your inner suit

Groups like the Association of Illustrators run business masterclasses advising on the nitty-gritty of finances and self-promotion. It's sensible to be au fait with the tax system and have a grasp of bookkeeping, but can you actually learn business flair?

Get the Creative Bloq Newsletter

Daily design news, reviews, how-tos and more, as picked by the editors.

Self-initiated work keeps the creative fires lit, so if you can make it pay hard cash too, that's a win-win situation. Further to this, being forced to think in a commercial way about your own work can help keep your feet on the ground.

Illustrator Emily Forgot has always made things to sell alongside her commissioned work, and reckons business acumen is something that comes with time. "The longer I'm working in the field of design and illustration," she says, "the more interested I am in the business side of things. I suppose it makes me feel more grown up when most of the time my work feels like play."

George Wu of pop-up design retailer Poundshop also thinks illustrators can benefit from some hands-on business perspective. "Since the recession there is a huge entrepreneurial spirit growing from designers taking business into their own hands," she says. "Understanding the commercial side of design makes you more receptive to your market and opens your eyes to what actually sells, rather than what you think should sell."

Neal Whittington of stationery and printed ephemera retailer Present & Correct echoes the whole 'follow your gut' school of decision-making. "I know what I like and am decisive in what I stock, but not necessarily in my own work," he says. "It does help to be able to see things in a monetary sense. That sounds terrible, but it's your living and it helps you edit things out and say 'no'."

Whittington ran Present & Correct as an online store for five years before opening a shop on Arlington Way in North London in 2013. Before Present & Correct, he worked as a designer and illustrator, for Monocle magazine among others, but these days does not see himself as just a shopkeeper ("not that there's anything wrong with that," he is quick to point out). The design for Present & Correct, from the shop's branding to its beautifully art-directed shoots, help keep Whittington's design muscles flexed.

"I miss it a little," he admits of his years spent working on design full-time. "I'd love to get my teeth into a fun little branding project. I make and illustrate things for the shop when I can."

From design to delivery

Despite being of an entrepreneurial bent, Anna Fidalgo and Roger Kelly of online stationery and homeware store Crispin Finn admit it's a challenge juggling the creative stuff with the demands of running a business. Their success is clearly down to lots of hard work, and they own the whole supply chain from idea to delivery.

"It's a learning curve trying to maintain both the physical production of everything and run an online shop alongside our client-based design work," says Fidalgo. "There are so many practical factors involved beyond making the work itself - there's a lot of daily admin to be done, budgeting for new materials, figuring out packaging, postage, customer relations, keeping the accounts ship-shape, all of that. And having an overall view of what and how we're doing as a business."

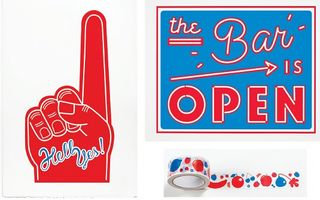

Distinctive for its restricted colour palette of red, white and blue, Crispin Finn is an example of an extra-curricular passion that ended up becoming a full-time pursuit. Couple Fidalgo and Kelly had separate day jobs as a designer and artist but collaborated out-of-hours on projects under the Crispin Finn moniker. When they started the venture, the aim was never to go full-time - Crispin Finn's development was a result of seeing how far they could push things, and out of sheer enjoyment.

Crispin Finn keeps most of its print production in-house, thus limiting costs - it would not be unusual to find the pair toiling late into the night in the screenprinting workshop installed in their studio to meet an order deadline. Proof that you have to be dedicated, exacting, and a touch bloody-minded to achieve what they do.

"With illustration you never know when the next job is coming and we feel that if you're not actively trying to make things happen, maybe things won't happen," explains Kelly.

"We have a long list of things we want to make and people we'd love to work with, so we're always pushing to try and get those things out there alongside the commercial work," adds Fidalgo. "The variety is what we thrive on. It keeps the daily challenges exciting, and means there is always something that needs doing."

Rip up the rule book

It takes guts (and perhaps a touch of foolhardiness) to leave clients behind and turn yourself into the main event. What happens if you decide to chuck your biggest client, or even all your clients?

Some trained illustrators have done just that, operating more like artists, communicating their own ideas and swapping clients for collaborators. The success of graphic artists like Patrick Thomas, Anthony Burrill and Rob Ryan is backed up by years of experience, knowing what sells and making confident decisions.

For Thomas, the leap came after a key exhibition. "In 2006 I had work in a show at the V&A and sold some editions, which felt good. I'd never had that much satisfaction doing commercial work so I decided that from then on I would concentrate more on doing my own thing," he recalls.

"Initially, I tried juggling it with commissions but soon realised that it had to be one or the other. It was in 2008 when I set up my first silkscreen press and decided to work 100 per cent on my own stuff that things really started to come together."

However, full-on independence is not the route for everyone, and it can be just as rewarding to perfect the art of working for clients and doing so in a way that is creatively satisfying. Illustrator Richard Hogg has been working almost full-time on video game Hohokum for a year and a half. He and collaborator Ricky Hoggart have never had a client as such for Hohokum, but Hogg says the collaboration - sharing ideas, work and deadlines - is motivating.

"I couldn't work totally on my own, it wouldn't be as satisfying," he says. In the time he has been funded to work on Hohokum he's had little time for other client briefs, but a few small jobs have kept his hand in, and he doesn't see himself making the move entirely to being a game designer.

"I like working [for clients]. It makes me sad when people are down on it because I really like briefs, I really like solving problems for people. And I quite like the idea of being a service - people pay me and I fix a thing, or make a thing they're happy with that helps their business."

A different perspective

"It boggles my mind that there aren't more people like me doing this," says Hogg of his position as an illustrator designing a video game. He sees the world of video games as rich pickings for illustrators and artists, who can make something special that stands out in the field and which they already have the skills to embrace.

Illustrators can also provide a fresh perspective on the world of gaming. For instance, Hogg interacts with games in a way that their makers didn't necessarily intend, exploring the environment rather than just killing the bad guys. This has ended up feeding into Hohokum.

"It's not something we set out to do initially, but we feel there is a lot of scope for making games that appeal to people who don't normally like games," he says.

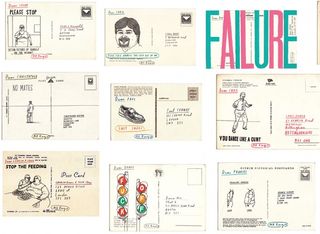

If Hogg is an example of an illustrator innovating in a field not normally signposted illustration, Mr Bingo is one who has set up his very own independent state, with a benevolent (and rude) dictator as its figurehead. Bingo has made a brand of himself, and is in the lucky position of being commissioned for his ideas and persona as well as his drawing style. So apparently loved is his work that people are prepared to commission him, through his unique Hate Mail service, to insult them. Living the dream, surely?

"In some ways I suppose I am," he muses. "It's certainly a pretty unusual way to make a living, and difficult to describe to new people you meet."

Bingo, too, still feels the call of commissioned work. "I could turn Hate Mail into a full-time occupation," he says, "but I'd run out of ideas fairly quickly. I wouldn't want to do it every day. It's definitely the most fun thing I've ever done, but doing anything over and over again always becomes dull after a while."

The agenda for illustrators moving in and redefining an existing field has been set by their forays into retail. Is there something in the water that draws illustrators towards shopkeeping? The canvas of four walls and a window onto the street perhaps holds something of the promise that illustrators are naturally tuned in to - the possibilities are truly endless.

Operating a rather less conventional retail business model, the aforementioned Poundshop, founded by George Wu and Sarah Gottleib in 2010, is a travelling emporium stocking work submitted by guest designers and illustrators, on sale for £1 to £10. It has popped up at venues from disused shops, to ad agency offices, to gallery spaces.

Wu and Gottleib collaborated with a different designer each time to create the interior. A major labour of love, they fit Poundshop in around their day jobs in teaching and design, but plan to grow it as a viable business.

"Hopefully we can start a mentoring scheme where we help designers to produce their items from idea and out onto the shop floor," says Gottleib of future plans. "Also at this point we are getting a lot of retailers asking for the designers' products to be sold in their shops, so this is something we're hoping to develop."

As a conduit to help self-initiated designs reach potential customers, Wu and Gottleib have a good perspective on the value of small-scale entrepreneurship in illustration. Is it an essential quality to succeed today?

"I guess it depends on what kind of designer you would like to be," says Gottleib. "I don't think we should feel that we have to be these crazy entrepreneurs and have crazy ideas just to make it. If you are good and work hard you will make it."

We are family

You have to be pretty comfortable with your own company as an illustrator - hours poring over a drawing or fiddly Photoshop job can mean you don't speak to another human for entire days. Which is why illustrators band together for company (and use a lot of social media). The need for sanity-saving compadres, collaboration and teamwork has spawned collectives, shared studio spaces and collaborative projects.

Nobrow is an amazing example of people power. Despite being a small machine, its output is prolific and exquisitely executed. "We have a wonderful team of people who work very hard to keep everything running smoothly," says co-founder Alex Spiro. "It sounds very banal, but having a good team of motivated and passionate people who believe in the company and what it does is crucial."

Making work that you can sell directly to the punters, as Nobrow does, also makes you feel more connected. Going from working in his spare room at home to opening a shop was a big shift in Present & Correct founder Whittington's daily routine.

"It's made me a lot more productive and structured," he says. "To go somewhere every day, with very certain tasks, is good. It's also nice to chat to people and sit in a room full of office supplies that I love."

For band of three Nous Vous - Jay Clover, Nicholas Burrows and William Edmonds - working as a threesome brings confidence as well as cameraderie. "Three people are better than two for making decisions and resolving any creative disputes," says Burrows.

"There are things that we'd never take on individually that we can do as a three-piece, such as our East London Mobile Workshop (ELMO), but that doesn't mean we share absolutely everything," continues Edmonds. "It's important to retain our own individual practices, otherwise it'd be boring and we'd be the same person. That's what makes it exciting - the potential and the energy created between the three of us."

It is also about community in a wider sense for Nous Vous. A joint venture with Studio Weave, Fiona Boundy and Hunt & Gather, ELMO takes them outside the illustration bubble and literally out on the road in a converted Bedford bus.

"Being involved in the community - locally, or in a wider sense - is part of why we do what we do," concludes Clover. "We enjoy connecting with people on a personal level, but we wouldn't ever want to give the impression that we're always doing that as a selfless thing away from 'work'. We want to be part of the world in general, not part of a clique or sub-culture, and these things really help us to do that."

Words: Angharad Lewis

Angharad Lewis is an independent writer and editor specialising in design and culture.

This article originally appeared in Computer Arts issue 222.

Liked this? Read these!

- The designer's guide to working from home

- Illustrator tutorials: amazing ideas to try today!

- Great examples of doodle art

Thank you for reading 5 articles this month* Join now for unlimited access

Enjoy your first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

*Read 5 free articles per month without a subscription

Join now for unlimited access

Try first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

The Creative Bloq team is made up of a group of design fans, and has changed and evolved since Creative Bloq began back in 2012. The current website team consists of eight full-time members of staff: Editor Georgia Coggan, Deputy Editor Rosie Hilder, Ecommerce Editor Beren Neale, Senior News Editor Daniel Piper, Editor, Digital Art and 3D Ian Dean, Tech Reviews Editor Erlingur Einarsson and Ecommerce Writer Beth Nicholls and Staff Writer Natalie Fear, as well as a roster of freelancers from around the world. The 3D World and ImagineFX magazine teams also pitch in, ensuring that content from 3D World and ImagineFX is represented on Creative Bloq.