Why choose non-photorealistic rendering?

Now that 3D photorealism is so achievable, why would you go any other way? Antony Ward explains the enduring appeal of NPR.

Since the birth of 3D, digital artists have strived to achieve one goal. For years we tried to reach it but technology held back our dreams, hampering our attempts with slow processors, limited geometry and basic shaders.

Finally, after over a decade of waiting, technology matured and we achieved the holy grail of digital art – the ability to generate the perfect digital double.

Initially this wasn't as ambitious as replacing a living actor with a virtual one, complete with flawless skin, dynamic hair and that hint of a soul behind the eyes. The dreams were more humble with us wanting something which didn't physically exist, even if it was representing something man-made rather than organic, but when seen could fool the viewer into believing it was real, a photo even.

Spot the difference

These days, digital art is used frequently to create photorealistic images, with most results being undistinguishable from the real thing. In films, virtual actors are common place, with some now completely replacing the human in all but voice.

Yet the best use of computer graphics remains those times when you don't ever realise it’s been used.

So after all that time, with all the blood, sweat and tears spilled trying to crack the photorealistic code, why should we then decide to go back and render anything in a non-photorealistic way?

It's a style thing

Just like any genre of art, 3D artists are in fact artists too. We have the same thoughts, same untameable imagination and are always experimenting with new styles and techniques to improve our work and make it more memorable.

Get the Creative Bloq Newsletter

Daily design news, reviews, how-tos and more, as picked by the editors.

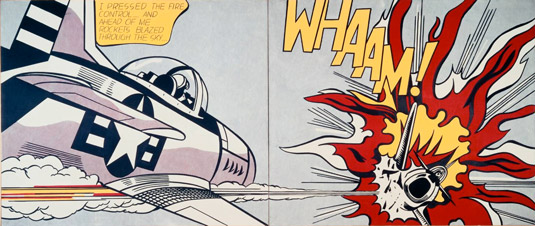

Style is the key word here. Imagine a painting by Picasso, Slavador Dali or Roy Lichtenstein. Now picture it stripped of its unique visual style and instead approached from a more realistic angle. Pop art guru Lichtenstein’s famous Whaam! would become a photo of a jet fighter shooting down another. Still an exciting image, but certainly nowhere near as unique or visually appealing.

This is quite a drastic example but you get the idea. Non-photorealistic rendering, or NPR as it's also referred to, is not just limited to painting but is in fact crucial in many other genres of art.

Illustrations are a good example. The artist is free to work outside the box and live without conventional restrictions, giving characters wildly exaggerated proportions and features, all to make them more, or sometimes less, appealing.

Child-friendly

This type of art along with a bright and colourful palette is ideal in appealing to children when they are learning to read, or indeed being subconsciously taught through any other medium.

If these characters were presented in a realistic way they simply wouldn't hold a child’s attention.

Comics and graphic novels are of course another area of illustration which relies entirely on the flexibility of style on each page. With the freedom of hand drawn images also comes a more engaging story line and visually stunning scenario.

Both of these are either not possible, or wouldn't be as attractive to the reader if presented in photographic form.

This leads us nicely into another form of storytelling. For years Disney has charmed audiences with its animations, all rendered in their own cartoon style. Would Snow White have the same longevity if the dwarves or the evil queen had been real actors? How about trying to make an actual live fox act in Robin Hood?

In these instances the style helped to tell the story, and also allowed Walt's imagination to run wild and replace humans with animals. Again, this gave the films more charm and appeal to audiences young and old.

The Pixar approach

Since then Pixar emerged and carried Disney’s torch into the 3D world but style has always been one of their key weapons. Yes, they do blur the lines occasionally, but everything always has the NPR edge to catch the eye, cause a tear to form and leave an ache in your heart.

It’s not all about entertainment, of course. NPR is also widely used in many other industries. Technical renderings of a product couldn't be possible if attempted in a realistic way.

An artist can create a product, like a vacuum cleaner, and then separate the parts to be rendered for a user manual. They can even create cross sections of the appliance if needed, to help illustrate areas in more detail. This is a technique which is not possible to replicate with a photo, not without a lot more time, effort and cost.

Technical manuals use NPR frequently where a photo just isn't physically possible, or won't aid in the explanation. Speaking from experience, when writing my own books and courses photos weren't even considered as an approach to recreate each step. When discussing polygon limits and textures they are better represented with renderings of the actual models, which again is another form of NPR.

There are more areas of life where non-photorealistic rendering is essential but I think you get the general idea. As with everything in life it comes down to personal preference but just as realistic images are needed in more simulation, or fact based areas, non-photorealism also has its place. In fact, you could argue that photorealism seems to be used more to provoke the mind, whereas non-photorealism is often aimed more towards the heart.

Words: Antony Ward

Win a trip to Los Angeles!

Masters of CG is a competition for EU residents that offers the one-in-a-lifetime chance to work with one of 2000AD's most iconic characters: Rogue Trooper.

We invite you to form a team (of up to four participants) and tackle as many of our four categories as you wish - Title Sequence, Main Shots, Film Poster or Idents. For full details of how to enter and to get your Competition Information Pack, head to the Masters of CG website now.

Enter the competition today!

Thank you for reading 5 articles this month* Join now for unlimited access

Enjoy your first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

*Read 5 free articles per month without a subscription

Join now for unlimited access

Try first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

The Creative Bloq team is made up of a group of art and design enthusiasts, and has changed and evolved since Creative Bloq began back in 2012. The current website team consists of eight full-time members of staff: Editor Georgia Coggan, Deputy Editor Rosie Hilder, Ecommerce Editor Beren Neale, Senior News Editor Daniel Piper, Editor, Digital Art and 3D Ian Dean, Tech Reviews Editor Erlingur Einarsson, Ecommerce Writer Beth Nicholls and Staff Writer Natalie Fear, as well as a roster of freelancers from around the world. The ImagineFX magazine team also pitch in, ensuring that content from leading digital art publication ImagineFX is represented on Creative Bloq.