Actually, that $1.4M 'blank' painting isn't a waste of time

In a world of passive TikTok videos, here's an artwork that forces you to participate.

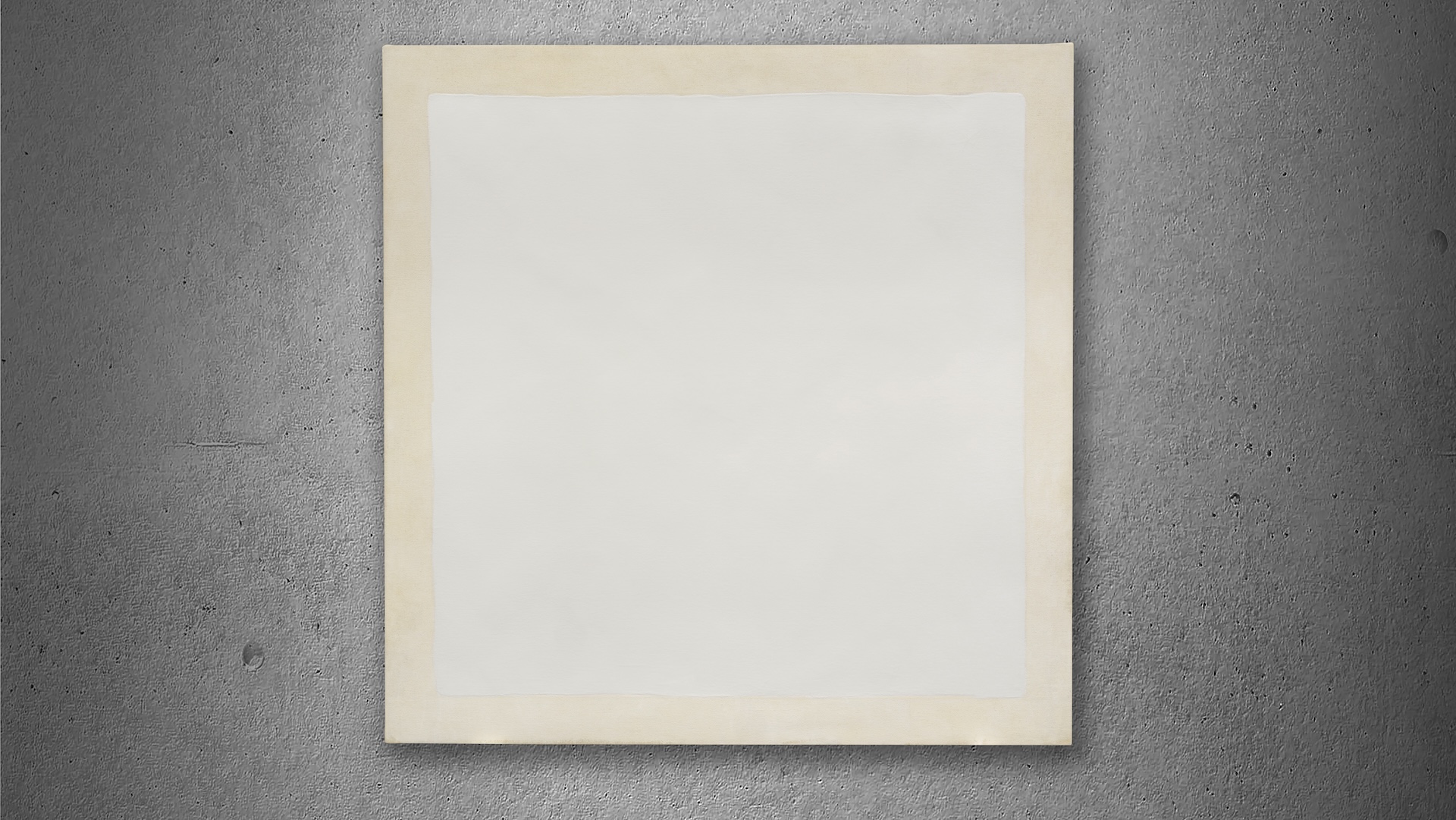

As I write this, I've got two tabs open in my web browser. One tab is an image of an apparently blank canvas by the American artist Robert Ryman. Titled General 52 x 52, the original just sold at auction for nearly $1.4m. The other tab is a TikTok video likening the voice of the new Manchester United manager to a character from Despicable Me. To be honest, I think I'm enjoying the TikTok video more than Ryman's painting.

General 52 x 52 sold last week at Berlin auction house Ketterer Kunst. Several news outlets compared it to the recent $6.2m sale of Maurizio Cattelan's Comedian, a banana, duct taped to a wall, bought and eaten by a Crypto entrepreneur. I've seen a lot of social media outrage directed towards Ryman, declaring the art to be a waste of time. And yet, while I might be getting more of an immediate laugh out of that TikTok video, I'd still take a 'blank' painting over it.

Last week, some pretty wild claims were made about Pantone's colour of the year: "unpretentious classic", "invites us to savour the small joys", "promotes peace and natural beauty while enhancing the overall quality of life". I never understood how a colour alone – rather than the way it was used – could do all that stuff, especially Mocha Mousse, a colour redolent of gastrointestinal strife. But I think Ryman's all-white paintings actually do what Pantone claims "mocha mousse" does.

Ryman wasn't fussy. He gave his paintings unimaginative titles because he didn't want the title to influence how you saw the work. He was known to exhibit his pieces in whatever order the shipping company delivered them. He didn't waffle on unintelligibly about his work, never claimed it contained all sorts of complex meanings and metaphors. He spoke sense about art, in his own lovely, clumsy way. He told one interview: "I wanted to paint the paint." He told another: "A painting has to do with, well, with paint, basically ... It's never so important what you paint, it's how you do it."

He painted on all sorts of surfaces: coffee filters, cold-rolled steel, fibreglass panels, corrugated cardboard ... But he stuck almost exclusively to painting in white. Ryman never developed. He deepened. And his motives were as pure as his medium: he wanted his viewers to enjoy "an experience of delight, and well-being, and rightness ... like listening to music." But you had to meet him half way.

Robert Ryman died at 88 in 2019. Aside from a few classes, he had no formal training in art. He was born in Nashville in 1930, moved to New York in the 1950s, wanted to be a musician, took music lessons with a blind pianist, jammed with jazz bands in Greenwich Village, then tried his hand at painting, and took a job as a room guard up at Museum of Modern Art so he could spend all day around art. He first met Mark Rothko in the museum's cafeteria. He held his first solo exhibition at the Bianchini Gallery in 1967, and sold not a single thing. In 2015, Bridge, another of his all-white paintings, sold at the Christie's auction house for more than $20m.

What about the sale price of the much smaller General 52 x 52? Can a stretch of canvas and a bit of paint ever really be worth $1,383,800? In one of my favourite Mad Men episodes, Bert Cooper buys a Mark Rothko and hangs it in his office. His employees at the Sterling Cooper advertising agency worry he'll ask them to interpret its meaning. Cooper hasn't exactly bought the piece because it moves him. He says: "that thing should double in value by next Christmas." This often goes unsaid when paintings sell for silly money. They're usually bought less for their artistic merit than their investment value.

Get the Creative Bloq Newsletter

Daily design news, reviews, how-tos and more, as picked by the editors.

But let's say the buyer bought General 52 x 52 for its artistic merit. What are they getting for their money? First things first: General 52 x 52 isn't blank or completely white, as has been reported. The centre is enamel paint, hard and glossy, a solid white, built up layer by layer, then sanded smooth, so it catches light. The enamel's framed by a different texture, a different white, the rougher off-white of the raw or lightly treated cotton canvas. The lines between enamel and canvas aren't hard, but fluffy, cloud-like. Because of the contrast between the two, because of the enamel's sensitivity to light, the centre square often looses it pure whiteness: you sometimes see it as beige-tined, or blue-tinted, or tinted ever so slightly green. The white enamel is so sensitive, the painting couldn't be transported for viewings. Effectively, buying it was the only way to get a good look at it. The painting will never look the same twice.

I've seen Ryman's paintings a few times. His whites have made me think of the sky, and the sea, and the tops of birthday cakes, and torn-up paper, and joy, and despair, and, on one occasion, absolutely nothing. "The viewer is challenged and becomes the creator of the art," said Simone Wichmann, an expert the Ketterer Kunst auction house. An image on my computer – no matter how large the file – could never really do Ryman justice. But there's more to it than that. His art forces you to participate. It's active, while much of today's media is passive.

That TikTok video likening the voice of Ruben Amorim to the voice of Gru provided me a moment's diversion. General 52 x 52 forced me to think, respond, participate. It made me write this piece.

Thank you for reading 5 articles this month* Join now for unlimited access

Enjoy your first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

*Read 5 free articles per month without a subscription

Join now for unlimited access

Try first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

Gary Evans is a freelance journalist and travel writer. He is a former staff writer for Creative Bloq, ImagineFX, 3D World, and other Future Plc titles.