Kirk Hendry

Kirk Hendry’s new animated film Junk is not only a long-held passion – it has proven to be a valuable tool for self-promotion. Ed Ricketts talks to the filmmaker

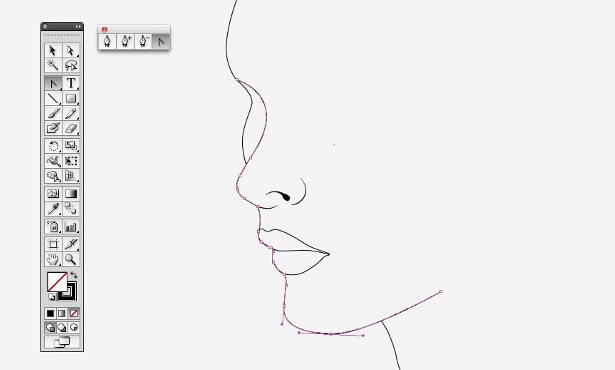

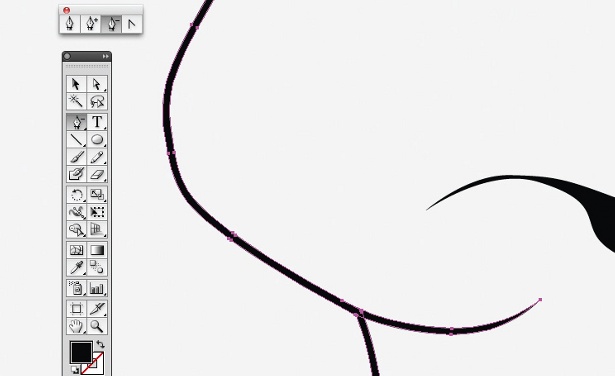

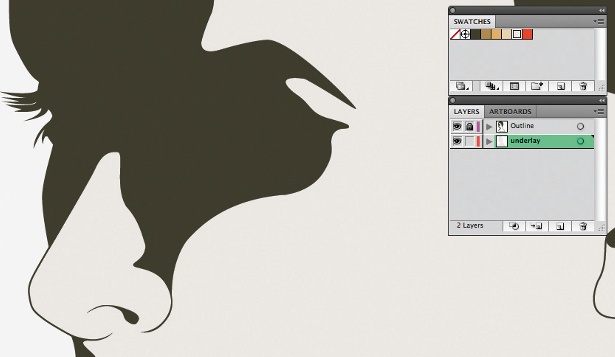

“I don’t really see any difference between a self-promotional piece and a creative piece in general,” says Kirk Hendry, writer and director of the animated short film Junk. “They’re the same thing, surely. All your creative endeavours are your calling cards.” Junk, already nominated for four film festival awards, is the story of a boy called Jasper and his obsession with junk food – and, on a more subtle level, the importance of following your gut instinct. Written and directed by Hendry and produced by Lydia Russell with support from the UK Film Council, it features a mixture of full 3D rendering and a 2D silhouette/shadowplay style that harks back to Hendry’s earlier work, Round.

The film is now on its festival run and the response has been phenomenal – both in terms of reaction to the story and visuals, and as a self-promotional tool for Hendry. He says he has won work on three commercials because of it, including a short for the World Wildlife Fund. “I guess if you can display that you can tell a story, with a certain level of production value – particularly if that production value has your own personal style – you will be able to get commercial work,” he says modestly. “But, you know, follow your instincts. Make what you wanna make, and then see who responds to it.”

This has certainly been the case with Junk, a long-cherished project for Hendry. It began life as one of a series of short stories he wrote for a potential children’s anthology TV show that he was planning. “I pitched the series to a well-known American children’s broadcaster in the UK, and they agreed to make some initial episodes,” he explains. Unfortunately, as pre-production progressed Hendry realised he was unhappy with the design and animation, and had to make the painful decision to pull the plug on the project. “That was a pretty hard thing to do, when it had seemed like a big break and was now going to turn out to be nothing,” he adds. “Then I decided to just make one myself. I knew it would be a long undertaking because I didn’t know anyone in animation. I had never made animation. It ended up taking way longer than I had imagined.”

Indeed, Hendry’s big break had been a long time coming. He was born and grew up in New Zealand, but had a hankering to move to London right from his very early teenage years. That move completed, he got into filmmaking as a production assistant with a company that made science programmes for the BBC.

It was around this time that the film and TV industry was moving from analogue to digital and, as with many other people, this was key to Hendry’s move into filmmaking. “The first Mini DV cameras were being sold, so production companies bought them because of their low price,” he says. “This meant you could borrow them at weekends, and the first Avid editing suites arrived. Wow, you could do dissolves, fades and audio mixes. People began using the word ‘non-linear’! It was amazing.

“It meant you could bypass the nepotistic route into the industry and instead do it on merit,” he adds. “You could now prove [who you were] by making your own films. It all just began to click, so I started making films after work.”

Despite being a labour of love, Junk would have been nigh on impossible for one man to complete in any reasonable timeframe, and Hendry was helped by a team of 20 artists over two years of production. The animatic and much of the early work, though, was created by him while he was still unemployed and working out of his bedroom. “The animatic had voiceover, temp music from classical records and soundtracks I had, and had basic movement to illustrate motion in shots. Having an animatic with music and sound effects gave it instant production value and power, even though the pictures looked pretty bad because it was my own stick figure storyboards.”

He also made a single mood frame of how he eventually envisioned the film to look, and emailed a link to the animatic, together with this ‘style frame’, to various producers around Soho. This time-honoured idea of taking a direct route paid off, with several studios taking an interest. Eventually he was taken on by th1ng, the production company where he produced Junk and where he now works.

He produced all the backgrounds for the film himself. “That was a daunting task as it took two days per background and I knew there were 70 shots in the film,” he says. “So from the outset I knew I had 140 days of Photoshop cutting-out in front of me. Then I learned to love and hate 3D – mostly hate. It’s incredible what you can do with it, but it takes ages to get something that looks good. I loved getting things out of Maya and into a compositing tool.”

What else did he learn during the process? “Well, expect a high turnover of staff. Low-to-no-budget films rely on inexperienced people looking for more experience; their enthusiasm for working for nothing will last, on average, two months, so you’ll spend a lot of time replacing people in the middle of shots. What at the time seems like hell is actually all part of the process and teaches you about producing.”

Initially, he says, he wasn’t regarding Junk as a form of self-promotion; given that it was supposed to be part of a TV series, he was fully prepared to have to compromise on budgets, style and time, to the point where it might no longer truly represent his own ideas.

It was only when he took on the film himself at th1ng, as a short project over which he had complete control, that it became a potential tool for promotion. But whether a piece is intended to be purely self-promo or not, he believes the overriding aim should be the same: to produce the best result you can, and to follow your initial idea as closely as possible. “You start off with the excitement of an idea,” he explains. “Then you’re propelled into action by the challenge of realising and executing that idea.”

He admits that by the end of the process you’ll probably be sick of the whole thing and never want to see it again – until the next big idea pops up and you start the whole cycle over. The key to a successful project – whether it’s a short film, self-promo piece or whatever – is in staying faithful to the concept rather than overloading it with exaggerated imagery just for the sake of it. “The techniques are there to bolster the way you tell the story or explore the character,” he says with regards to filmmaking in particular.

“Be wary of excessive production design and lavish photography – they’re the icing, not the cake. Great characters never date and we will follow them anywhere. But it is the hardest thing to write great characters and tell your story in a compelling way. That’s why so many films tend to have unnecessarily seductive cinematography and really lavish production design – [to act] as a distraction from the unengaging characters they have left the audience with.”

These days the quality of the final product is only part of the self-promotional picture, as Kirk points out. With so many easily-accessible outlets available to publicise your work, you should start planning your publicity long before the project is actually completed.

“Do a blog that charts the production and success of the project,” he suggests. “If your work looks interesting enough then people will follow it and help do promotion for you by forwarding it onto friends or re-posting it on other industry sites. Make a website for your project that has a trailer or snippet of your work, as well as information about it. Try and think what press and media will need and have it there so they can download it if they have a page to fill – press release, images and so on.”

Although it might not be everyone’s style – Banksy seems to have done alright for himself, after all - it’s also important to put a more personal face on the talent behind the project, he believes. Like it or not, we live in an age where people love to know, or think that they know, every detail about the life of a celebrity, artist, writer or filmmaker. “So make video featurettes about various aspects of how your project was made,” he says. “If people like what you have done, they will want to learn more about you – and putting a face to a name breaks down a huge barrier. It’s very useful at festivals, or any event where you’re showing your work, where people tend to know names but not faces. If you came across as agreeable in the ‘making of’ videos, this will make it easier for people to come over and say hello.”

Ultimately, he thinks the key to self-promotion is perhaps the most obvious one, regardless of all the publicity: “Be yourself. There is only one you. There is much value in that.”

Thank you for reading 5 articles this month* Join now for unlimited access

Enjoy your first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

*Read 5 free articles per month without a subscription

Join now for unlimited access

Try first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

Get the Creative Bloq Newsletter

Daily design news, reviews, how-tos and more, as picked by the editors.

The Creative Bloq team is made up of a group of art and design enthusiasts, and has changed and evolved since Creative Bloq began back in 2012. The current website team consists of eight full-time members of staff: Editor Georgia Coggan, Deputy Editor Rosie Hilder, Ecommerce Editor Beren Neale, Senior News Editor Daniel Piper, Editor, Digital Art and 3D Ian Dean, Tech Reviews Editor Erlingur Einarsson, Ecommerce Writer Beth Nicholls and Staff Writer Natalie Fear, as well as a roster of freelancers from around the world. The ImagineFX magazine team also pitch in, ensuring that content from leading digital art publication ImagineFX is represented on Creative Bloq.