Get started with web accessibility

What is web accessibility? We explain accessible web design principles, and share top tips and resources for getting started.

Web accessibility refers to the degree to which a website's UX design is available to as many people as possible. Most often, when we’re talking about web accessibility, we are describing how people with disabilities can access the web.

The common symbol of web accessibility is screen readers. A screen reader, as the name suggests, is an assistive technology that reads the text content of the screen to the person using the computer, output as speech audio or braille.

Screen readers are usually associated with users who are blind or have impaired sight, but they can also be valuable to people with learning difficulties who find reading strenuous, or people who would just prefer to listen to audio content rather than reading text.

Much like the accessibility of a building is not just about wheelchair access, the accessibility of a website is not just about screen reader access

Much like the accessibility of a building is not just about wheelchair access, the accessibility of a website is not just about screen reader access.

Paying attention to making a site accessible for one set of needs can often benefit other people, too. When we design our sites to be usable by many people, with a wide range of needs, we call it inclusive design.

When we’re looking at how to make our sites usable for a wide range of needs, we can focus on five broad areas: visual, auditory, motor, cognitive, and motion-sensitive. We'll look at those areas in more detail now.

Visual accessibility: Make it easy to see

Making our sites easy to see can benefit people with visual impairments, people who are colour blind, and even people who are just trying to use their mobile device in bright sunlight.

Screen readers can benefit people who cannot see the contents of the screen. So in order to make our sites accessible to screen readers, we can start by trying to use relevant HTML elements to describe our content.

For example, use <ul> for an unordered list. Not only will this make it easier for a visitor to understand how that chunk of content differs from plain text, but it will also enable the browser to provide additional cues and behaviour.

When we use <ul> to describe the list, and <li> for each list item, the browser can inform a user that there is a list, how many items are in the list, and enable the user to easily skip between items.

Providing text alternatives to visual content is another easy win. If we use the alt text attribute on images to provide descriptive alternative text, it won’t just benefit people using screen readers.

If someone is on a poor internet connection, and a page’s images haven’t loaded, the alternative text can benefit them too. Plus when a search engine bot indexes a site, it will also use the structure defined in the HTML to assess the relevance of the content, and what to present in search result previews.

Auditory accessibility: Make it easy to hear

Providing alternatives to audio content can benefit people who are profoundly deaf, have mild hearing impairments, or even people who have forgotten their headphones but are trying to watch a video from the quiet carriage on a train.

Audio and video content can be completely inaccessible if alternatives are not provided. Captioning and subtitles can be costly and time-consuming, but are increasingly used for videos on social media, as these videos often autoplay without sound.

Captioning these videos doesn’t just work for people with muted audio, but also for people with hearing impairments. For longer audio and video, transcripts can be an efficient text alternative, and they are also easily indexed by search engines.

Motor accessibility: Make it easy to interact with

Since the advent of touchscreens and mobile devices, we are more aware of how differently people can interact with the web, depending on how they hold a device and the input required. People with limited fine motor control can additionally find it difficult to move a mouse accurately, or can find typing time-consuming and tedious.

One important way to improve a site’s interaction is to ensure keyboard navigation is possible

We can make the interactive elements on our sites more accessible by increasing the hit areas on links and buttons, so they require less accuracy with a mouse or touchscreen.

Making forms with fewer free text fields can limit how much typing is required, and providing preset options through checkboxes and radio buttons can help someone provide more information without needing to type so much.

These considerations could also benefit a person just trying to use a touchscreen out in the rain, where their touch and typing accuracy is reduced.

Another important way to improve a site’s interaction is to ensure keyboard navigation is possible, since many people using screen readers will rely on their keyboards to interact with a page.

Considering how a person could use a site without hover or click functionality may also benefit people using mouse alternatives such as head-tracking, eye-tracking, or foot-operated mice.

Cognitive accessibility: Make it easy to understand

The content itself also needs to be accessible. Making your content and interface easy to understand could benefit someone with learning difficulties. Ensuring text content is concise will make a difference to someone who finds reading difficult and time-consuming.

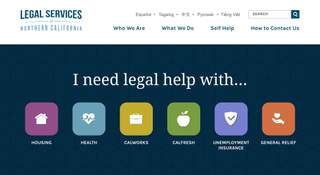

Using plain language could also help someone who speaks a different language natively, so doesn’t understand metaphors or jargon. Even if a person is in a stressful situation and just needs to find the information quickly, using headings and lists will make it easier to skim through a large block of text to find the required information.

The Legal Services of Northern California website knows its visitors are likely to be there because they need legal help, so the homepage is designed to quickly direct them to the most relevant information.

Designing for seizure-prone and motion sensitive visitors

We can generally avoid causing seizures in visitors to our websites by avoiding rapidly flashing content.

Motion sensitivity is a little more complex. Since animation and parallax scrolling became very popular, it can be easy to make people with motion sensitivity ill through inconsiderate design. It is always best to give the visitor control over how much motion there is on a page, and to avoid suddenly triggering animation without first giving the visitor the ability to disable it.

Get started with accessible web design

These simple examples are just a tiny preview of how we can improve accessibility on the web. Much like learning about responsive web design or frontend web development, accessibility is a field where best practices are continually evolving and improving.

Following the work of accessibility experts and advocates will help you stay up to date. Integrating accessibility into your research and testing practices will ensure you understand accessibility in the context of your own projects.

To get you started, here are a few accessibility resources:

- Accessibility For Everyone book by Laura Kalbag

- Inclusive Design Patterns book by Heydon Pickering

- A Web For Everyone book by Sarah Horton and Whitney Quesenbery

- Color Accessibility Workflows ebook by Geri Coady

- Tink blog by Léonie Watson

- The Paciello Group

- Axess Lab articles

- The A11y Project accessibility tutorials

- Web Axe blog and podcast

- HTML5 Accessibility site – tests which new HTML5 features are accessibly supported by major browsers

- W3C Web Content Accessibility Guidelines

Related articles:

Thank you for reading 5 articles this month* Join now for unlimited access

Enjoy your first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

*Read 5 free articles per month without a subscription

Join now for unlimited access

Try first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

Get the Creative Bloq Newsletter

Daily design news, reviews, how-tos and more, as picked by the editors.