How gender affects design

An increasingly gender-fluid world is changing design around us, for the better. But this is just the beginning.

2018 was the year that witnessed the Women’s March, Beyonce’s empowering set at Coachella and a defiant global female movement in the form of #MeToo. Coincidentally, it also marked the 100-year anniversary of the female right to vote in the UK. Following years of relentless campaigning, in 1918, eight and a half million British women finally secured the right to have their say.

Compared to 1918, women are now a lot more free to express themselves and to live independent lives. We are the most powerful consumers on the planet, accounting for 85 per cent of all purchasing decisions. And yet the question remains: have we come as far as we would like to think? As an industry, is there more we can and should do to embrace equality?

Sexual liberation and design

The 1950s marked the golden age of booming consumerism and advertising that glorified the idealistic housewife. The 1950s female was the perfect companion: subordinate, grinning, and always willing. Her favoured products included Brillo Soap pads and Tide (“Tide’s got what women want!”). The 1960s saw the design of the first seatbelt, to male specifications. A design that means female drivers are 47 per cent more likely to be seriously injured in a car crash.

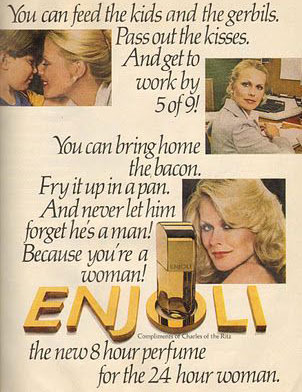

Entering into the 1970s, we witnessed a change in tides for female liberation: feminism, greater sexual freedom, the start of the fight for equal pay. Enjoli launched the eight hour perfume for the 24-hour woman, who could “bring home the bacon, fry it up in a pan and never let you forget you’re a woman”. There was a slight shift towards both recognising and celebrating the multi-faceted roles of women.

A gender-fluid world

And as our world has shifted, so have our attitudes: 2018 marks a year where more young people are rejecting traditional gender labels, where gender can be defined in 71 different ways, where brands from Zara to Gucci have launched gender-neutral collections, to much acclaim. The focus has shifted from who you are designing for, to why. And many brands are excelling.

Aesop creates beautiful skincare packaging, using dark bottles that focus only on what the product does for you. US-based Maude has redefined adult products, with organic, tasteful, genderless condom designs.

For cosmetics, the shift is greater still. Once upon a time the realm of the female, beauty today sees no boundaries. ASOS’ Face & Body collection uses bold, vibrant packaging that can proudly sit on the dressing table of whoever wishes to use it. Launched in 2018, Canadian skincare brand, Non-gender Specific, offers only one product: the Everything Serum. The conditions for use? That you are human.

The pink problem

But, if we think back to the infamous 2012 launch of BIC for Her, when it comes to packaging equality we still have some way to go. Take a pen, one of the most generic genderless products. Add some glitter, pink, a “thin barrel to fit a women’s hand”, a handy ‘for her’ label, and hey presto – a pen for women. Cue hilarious reactions from women all over the world. With men predominantly at the global helm of design, the tendency to revert to the pretty and pink strategy remains rife (a privilege we pay, on average, seven per cent more for).

Moving forward

Solving this disparity has to start from within our own industry. I am proud to be part of a creative team at Interbrand London where I myself am creative director, and am led by an intelligent, bold female executive creative director. But this seems to be the exception.

Despite women accounting for 46 per cent of the advertising industry, just 11 per cent are creative directors. And we remain guilty when it comes to gender delegating. It’s a beer brand? Dave would be best on that one. Packaging for perfume? Lisa should lead that. Why? Because she will definitely understand the end-user better. It’s gender bias.

Thankfully we are in 2018. Where the time is ripe for us to drive change. To assign people to projects, based solely on their expertise, interests and capability. After all, who says that a woman can’t design a male razor? (maybe razors don't need to be gendered at all?) That a man could not design the next innovation in sanitary care?

I have a male designer in the team at Interbrand who has done just that. We know that the most effective innovations are those that are completely inclusive. One of my favourite projects to date was designing a range of motor oils, targeted at Russian alpha-males. Certainly not pretty or pink. If that isn’t proof that a woman can understand exactly what a man wants, then I’m not sure what is. So let’s rewrite the rules and design for the person, not the gender. And by 2118, raise that 11 per cent to 50 per cent.

This article originally appeared in Computer Arts magazine. Buy issue 281 or subscribe here.

Related articles:

Thank you for reading 5 articles this month* Join now for unlimited access

Enjoy your first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

*Read 5 free articles per month without a subscription

Join now for unlimited access

Try first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

Get the Creative Bloq Newsletter

Daily design news, reviews, how-tos and more, as picked by the editors.