How two artists made a game that plays like interactive theatre

Patrick Blenkarn and Milton Lim created live collaboration game asses.masses with no previous coding experience.

Visit the asses.masses website to find out about upcoming performances. The next shows are:

- 2025.03.29 | PAMCUT + Risk/Reward, Portland, USA (EN)

- 2025.04.05 | Bradford UK City of Culture, Bradford, UK (EN)

- 2025.04.12-13 | Battersea Arts Centre + London Games Festival, London, UK (EN)

- 2025.05.18 | auawirleben, Bern, CH (EN)

- 2025.05.24 | The Theatre Centre, CA (EN)

- 2025.05.25 | The Theatre Centre, CA (ES)

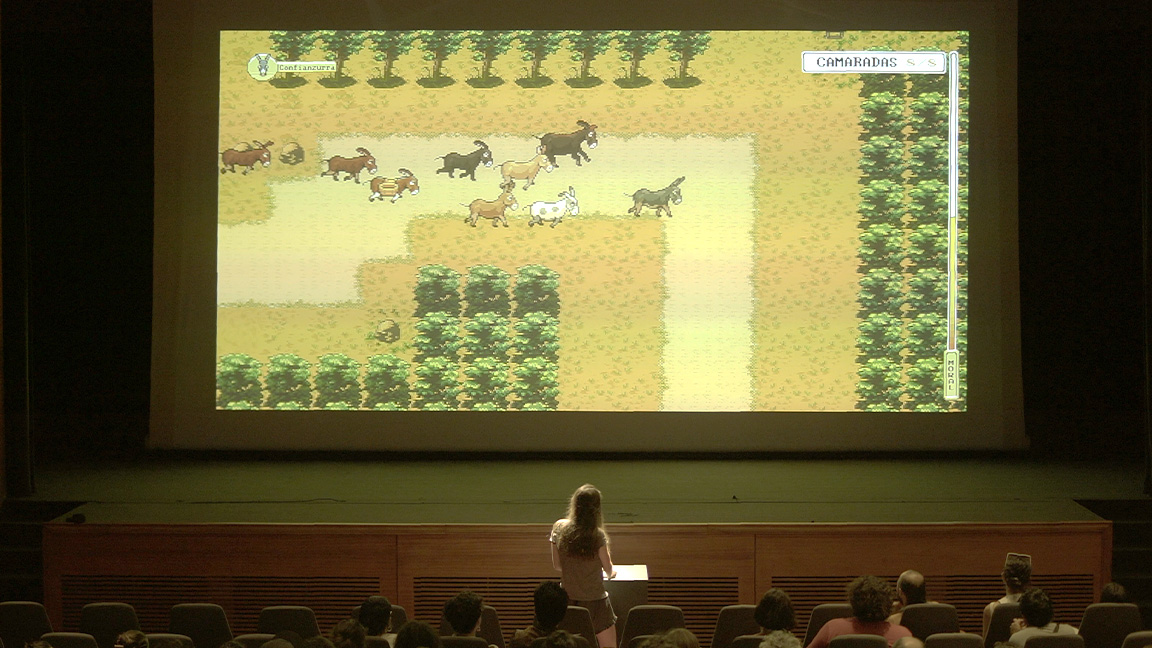

Patrick Blenkarn describes what happens in a performance of asses.masses, the collectively played video game designed by him and fellow Canadian Milton Lim. It begins with the audience being handed popcorn, which is the first sign this isn’t a typical type of theatre. Then the lights go down, and a spotlight comes up on a single game controller.

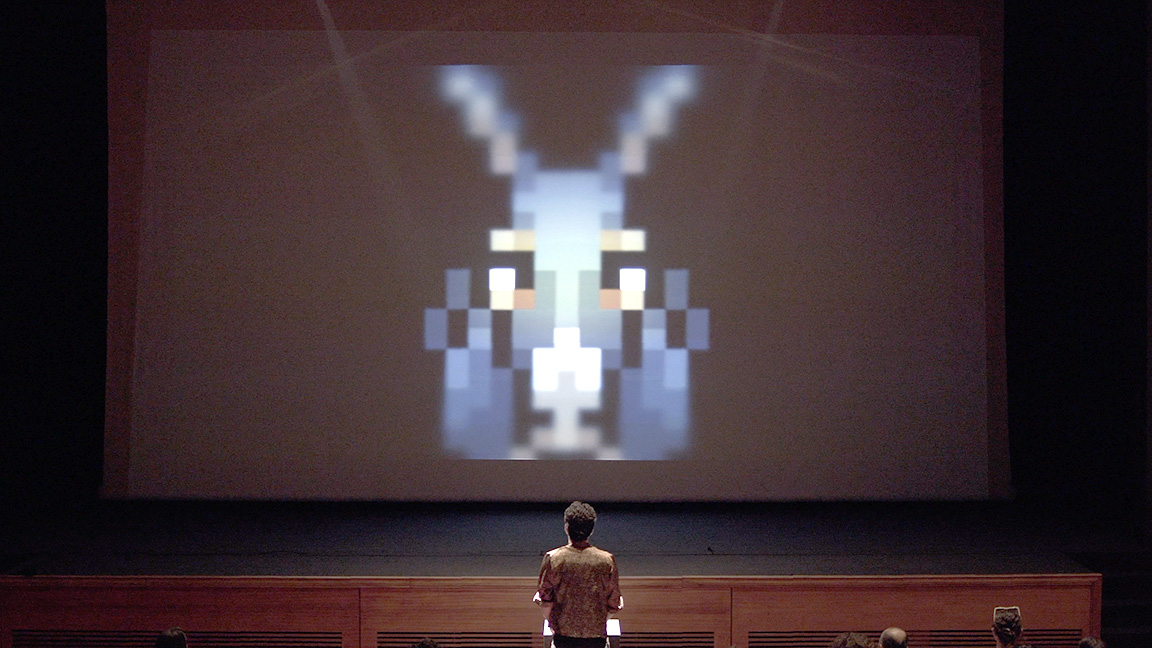

From then on, Patrick says, it’s entirely up to the audience to decide what happens next. “When the audience self-elects – somehow, at some point – a person to step out of that crowd and pick up the controller, the game starts. And what ensues is an eight-ish hour adventure of a herd of donkeys trying to get their jobs back from a world that is more interested in machines.”

Once upon a time, the donkeys ploughed the fields and pulled carts of coal, but those days are no more thanks to the march of technology – much like how AI and other systems are threatening to make some human jobs redundant. “There is a very deliberate parallel that we wanted to make,” says Milton.

But the game’s narrative covers various different angles. “We have many different perspectives on being pro-technology, anti-technology, being for the herd, for the individual. And we wanted to do that because it's not one player playing this video game: we wanted to encourage the fact that there's going to be multiple perspectives in the room.”

With interactive events and art installations, such as the Unreal Engine powered Frameless proving there's a gap for in-person interactive spaces, asses.masses is a creative approach the idea, one that adds a sense of theatre and community into the mix.

It's a game about building a community

Although only one person has their hands on the controller at any one time, asses.masses is designed to be a collaborative experience, says Patrick, and groups quickly self-organise so it becomes natural for people to take turns at being in control. He says, “At the beginning there is a kind of quiz, and in this first 10 minutes, the audience really learns that they're going to need to talk out loud with the person up there.”

This sets the tone for what’s to follow. “For example, a question will all of a sudden be in German or Spanish, and so the person [in the audience] who has that superpower of speaking one of those languages all of a sudden is like, ‘I have to speak, I have to help the group, because I have the knowledge’.”

Daily design news, reviews, how-tos and more, as picked by the editors.

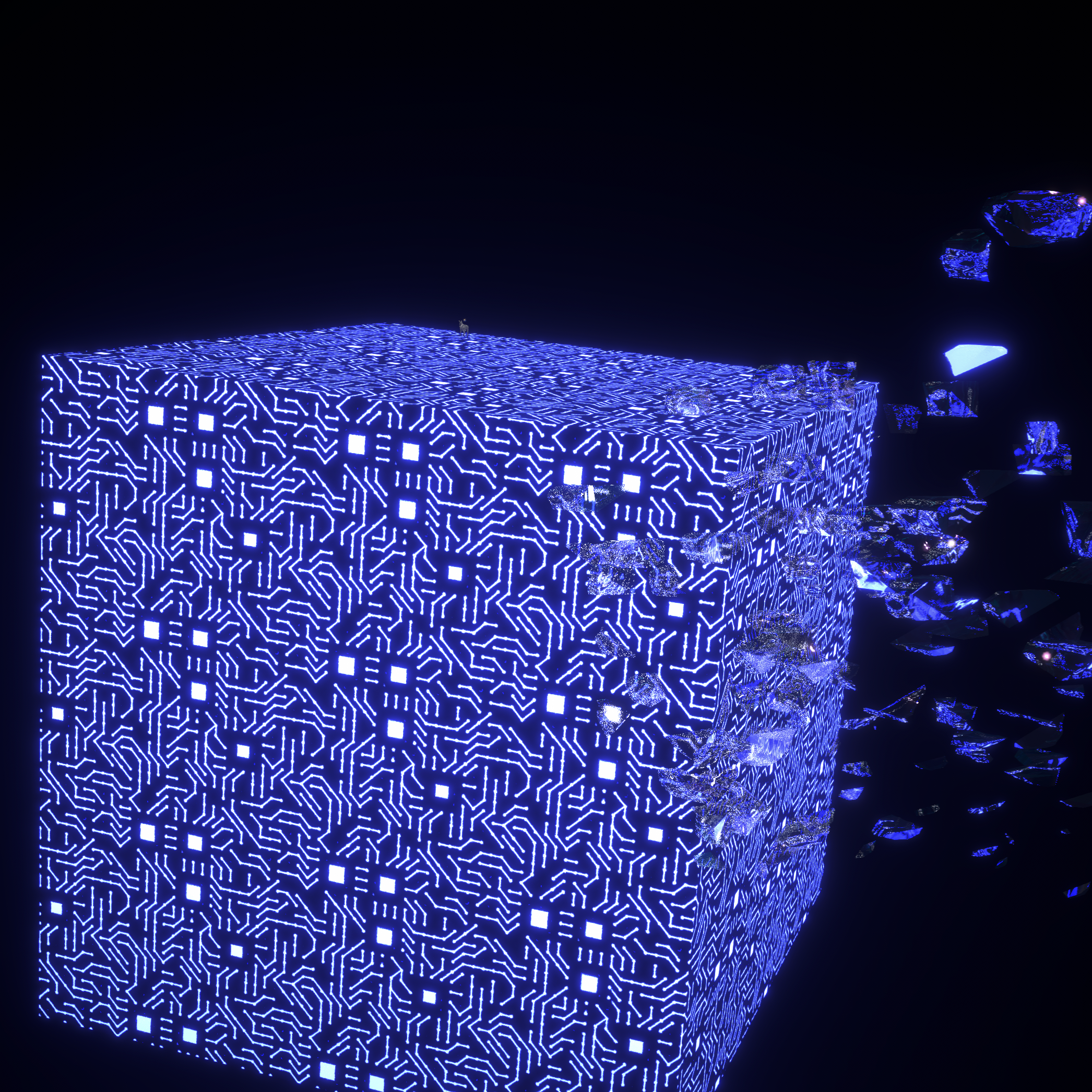

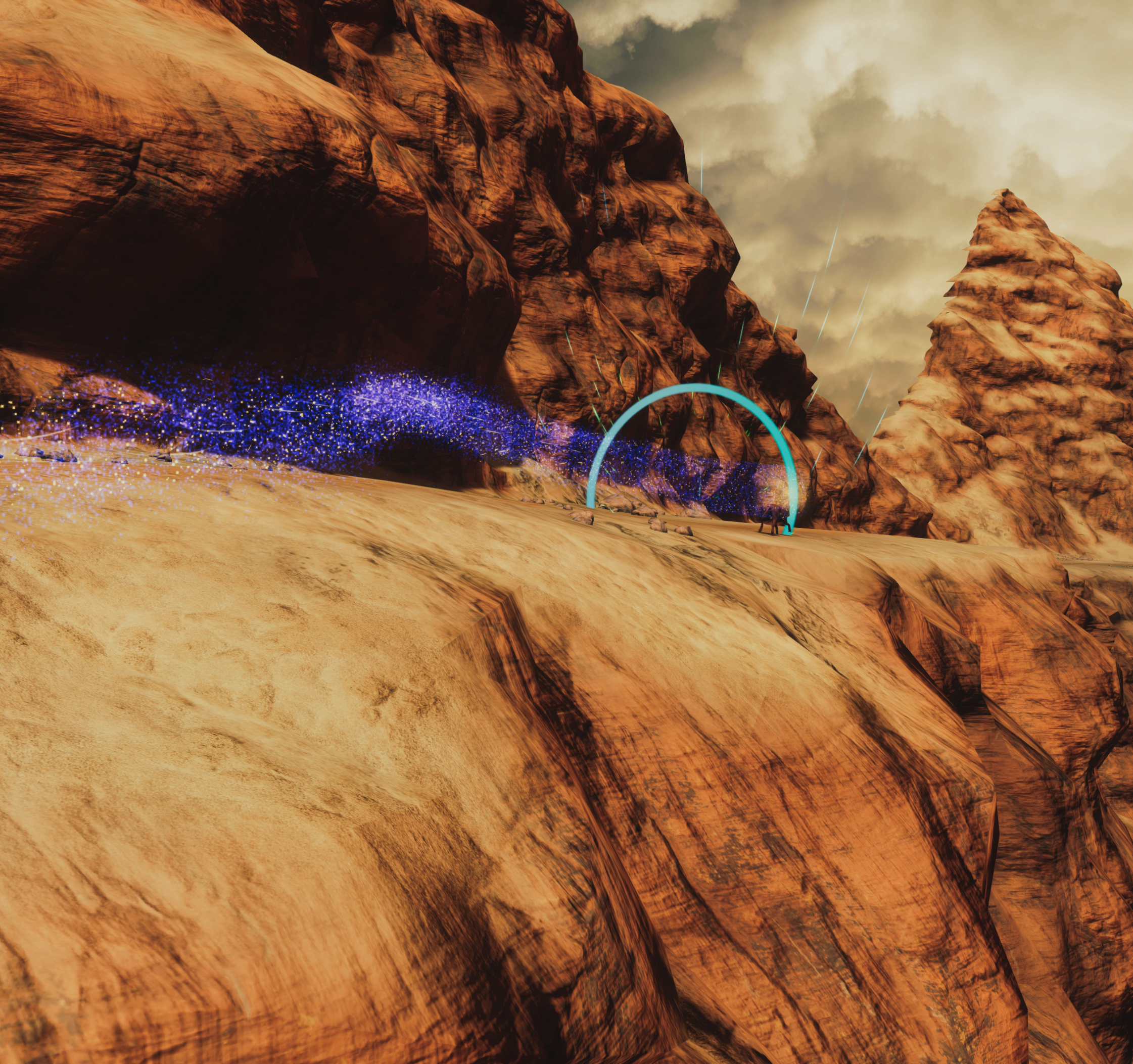

The game itself is split into ten episodes that are played over seven–to-eight hours, with regular breaks for food. Along the way, the game evolves through various different genres, like RPGs, racing games and platformers, with the material world being represented in 2D, while segments set in the astral plane are in 3D. Each episode focuses on a different topic and a different donkey protagonist.

“In episode six, there's a particular thing about family and motherhood, in episode nine, there's a thing about ambition, and in episode three, there's a thing about isolation and curiosity and play,” explains Patrick. “And each of these donkeys give us a [different] perspective.”

Both Patrick and Milton come from an arts and theatre background, and they previously collaborated on the collectible trading card game and live art performance project culturecapital. But neither had any programming experience, so creating asses.masses in Unity involved a steep learning curve.

“We learned how to make video games in the process,” says Milton. “I will say first and foremost, kudos to Patrick, who became the programmer of the whole show and learned from scratch how to code.” Patrick adds that the COVID pandemic happened during the early stages of the project, which “put everything into 200% overdrive” and allowed him to focus solely on programming, since his other work suddenly disappeared.

The process involved long hours of crunching through YouTube tutorials and learning node-based programming from scratch, but it helped that the pair were already proficient in Photoshop and Illustrator. “Over time, we learned how to do music and pixel art, and put all these things together to make the first version of asses.masses, which for two years was only episode one,” says Milton. “It was ironically the most amount of labour one could imagine to try and make this show about labour.”

From a practical perspective, Patrick says it was extremely difficult to find Unity plug-ins that matched the pair’s exact needs when it came to things like creating dialogue. “A lot of them are not designed to handle sequences of actions,” notes Patrick. “We're theatre people. It needs to go: lights on, pause, this thing happens, this other thing happens, you get control, and so on.”

The team experimented with game development software and tools like ink and Twine for branching dialogue, but they were frustrated with the limited interfaces. “We had a team of writers – Milton, myself and Laurel [Green] – and you needed to be able to see everything all at the same time,” says Patrick. “We wanted to be able to have images and prototypes and animatics and stuff like that next to lines. Writing for us is inseparable from the game design, inseparable from the environment design: it's just all got to be in the same room.”

The solution was Miro, a virtual workspace that enabled the team to plan out the dialogue and visuals of each episode in meticulous detail, putting everything on one enormous worksheet. In fact it got a little too big, in the end. “It doesn't open on iPads anymore,” smiles Patrick. “They can't handle it.”

The team’s ambition grew over time. “As we got more technically capable, we started to build more complicated games,” recalls Patrick. “We started to look less at narrative games and more at games like Mario Party, trying to figure out, ‘What is a good game to watch, as opposed to a good game to play?’ Our example often is that Overcooked is really fun to play, but it's chaos to watch. It's really hard to figure out who's doing what.” The team did a series of tests where they invited the public to play games like Resident Evil, Goat Simulator and The Legend of Zelda to try to understand what types of games could “fill a room with emotion”, says Patrick.

Gradually, over the course of the past few years, Milton and Patrick have added more episodes to asses.masses to bring the total number up to ten, and the pair have worked with a number of writers, artists, programmers and translators to expand the project and bring it to theatres around the world, in places like Mexico, Germany, Italy and Argentina.

The plan is to continue touring the game for the foreseeable future. “We've been asked many times if we'd ever package it and release it on Steam,” says Milton, but the pair have no plans for that right now. “For us, it's important to still uphold the integrity of the artistic gesture, which is in a space, in a community.”

And their next project could be completely different. “We're not interested in just doing the same thing over and over again,” says Patrick. But perhaps asses.masses will inspire artists to create similar social games in the future. “We hope other people see it and feel like: ‘I can make a game. They did’.”

If you're inspired by the duo's journey, then read up on the best software for game development as well as the kind of tech you need, such as a recommended drawing tablet and perhaps even upgrade to a new laptop for game development. Maybe you can bring your idea to life too.

Lewis Packwood has been writing about video games professionally since 2013, and his work has appeared in The Guardian, Retro Gamer, EDGE, Eurogamer, Wireframe, Rock Paper Shotgun, Kotaku, PC Gamer and Time Extension, among others. He is also the author of Curious Video Game Machines: A Compendium of Rare and Unusual Consoles, Computers and Coin-Ops (White Owl, 2023).

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.