The secrets of the interactive drama that is literally game-changing

Why Quantic Dream's Beyond: Two Souls could set a new bar for the next generation of video games.

The notion that a single killer app can be responsible for the success of a gaming platform holds less weight in this day and age, yet in the land of the games consoles a handful of development studios do still have the ability shift the balance of power. Quantic Dream is one such studio.

Founded in 1997, the Paris-based studio debuted with Omikron: The Nomad Soul, an idiosyncratic collaboration with David Bowie, and has endeavoured to blaze a unique trail ever since.

Pioneering a story-heavy style of gaming dubbed interactive drama, the studio has refined the use of performance capture in real-time rendering, most notably in its 2010 release Heavy Rain. That game redefined expectations about what could be achieved with Sony's PlayStation 3 technology, selling two million copies and bagging a shelf full of awards into the bargain.

Potential game-changer

Now, after the release of the PlayStation 4, Quantic Dream has stubbornly drawn attention back to the PS3 with the release of Beyond: Two Souls, another interactive drama and another potential game-changer. Such is the scale of ambition in terms of storytelling and graphical complexity, it could easily be mistaken for a standard- setting debut title for the next generation.

"At one point we did actually contemplate the possibility of releasing it exclusively on the PS4," admits executive producer Guillaume de Fondaumière. "However, we decided we'd like to release one last game on the PS3 before moving on, and our work on Kara [a tech demo unveiled in early 2012] gave us confidence that we could achieve our goals in terms of graphical quality."

Nevertheless, Guillaume admits that replicating what had been achieved in that seven-minute showcase within the context of an actual game and maintaining the same graphical fidelity through dozens of hours of animation was not without its challenges.

"Capturing the performance of actors over the course of one year, shooting almost every day, and then post-processing and integrating more than 50 hours of high-quality animation with real-time rendered characters and environments was one of the toughest tasks our team has ever had to complete," he reveals. "It ultimately required the flawless collaboration of a great number of departments at our studio."

Get the Creative Bloq Newsletter

Daily design news, reviews, how-tos and more, as picked by the editors.

Hollywood talents

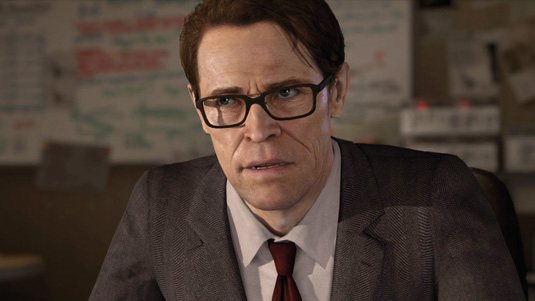

In fact, close to 200 people eventually worked on the project during its 34-month gestation, not including the 100-plus actors contributing performances to the game. These actors include Ellen Page in the role of lead character Jodie Holmes and Hollywood veteran Willem Dafoe as scientist Nathan Dawkins.

While Hollywood stars of this calibre and fame have lent their skills and faces to video games before, none have been quite as spookily replicated in-game as the actors are here. While some might take issue with the studio's claim that its use of big names was based solely on a desire to harness acting skills rather than for marketing muscle, Guillaume says that choosing to recreate their likenesses so faithfully offered practical advantages.

"Modelling the characters almost one-to-one against the real-life actors from high-precision scans meant that we had the video reference from the performance-capture sessions to look back to and compare against at all times," he explains. "It also meant that there wasn't too much cumbersome retargeting required, which always leads to quality issues or loss of subtlety in the performance."

Technical references

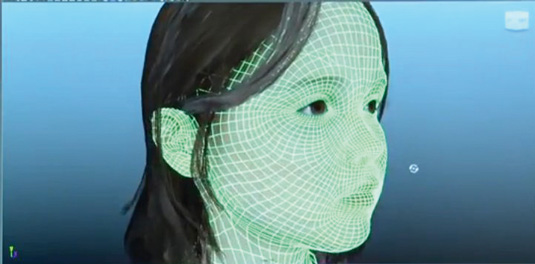

Full body scans with Artec 3D hardware provided the starting point for character models, with actors scanned in a variety of clothes and with multiple facial expressions - the latter to help later with wrinkling and skin deformations.

"For each actor, from the leads to passers-by, we worked with around 500 technical reference photos of body, head, eyes, hair, fine details, clothing and so on, all with a specific light setup," says art director Christophe Brusseaux. "We also manually took a lot of anatomical measurements, to ensure we preserved the proportions for each actor as much as possible in-game."

While motion capture has long been a staple in the games industry, with several larger developers and publishers even running their own facilities, Quantic Dream is particularly experienced at both directing actors and accurately capturing their performances. The studio established its first capture stage back in 2000, and has relied on it for every title developed since, as well as for cinematics created in 2004 for French 'digital backlot' movie Immortal.

"Additionally, we hired some new talent with experience working on mocap shoots for American films including The Polar Express and Spider-Man,” says Guillaume. He stresses, however, that there are some key differences between performance capture for game and for film.

"A feature film is a couple hours long, so there's not usually more than two hours of linear animation to create, whereas for Beyond: Two Souls we had to generate more than 50 hours. Our budget for post-animation was also probably 10 to 15 times smaller than that of something like Avatar, so we had to come up with original solutions that would enable us to go almost straight from the capture stage to our real-time engine with a reasonable level of quality."

We adhered very closely to the motion capture, especially for the 'performance' parts

"We adhered very closely to the motion capture, especially for the 'performance' parts," adds animation director Kenn McDonald. "When you go to the expense and trouble to bring in actors of the calibre we had here, you don't editorialise. I'm not going to second guess Willem Dafoe's acting choices! So our job as animators was to get those performances up on the screen in the context of the game as faithfully as possible. Sometimes the physical aspects of a performance required some adjustment, but we never changed the intent or the facial performance or dialogue."

World-class performances

McDonald says they split the animation work into two categories, 'Motion Kit' for standard gameplay actions such as walking, running and climbing, and then 'everything else', which included conversations, emotive scenes, complicated one-off physical actions, combat and so on - though the delineation was blurred somewhat, with performance pieces utilised multiple times included in the Motion Kit (Mokit), and one-off 'standard' actions placed in the performance category.

The animation team was then split into three, with four animators focusing on Motion Kit work, 14 mostly responsible for body performance animation, and then up to five concentrating on facial performances and dialogue.

"In the case of the 'Mokit', the animators frequently reworked the motion capture to make sure the actions would work well as cycles and transitions, but always took care to respect the motion capture and use it as the foundation," says McDonald.

"With the performance scenes we tried to stick more closely to the original data, but still spent time refining the motion based on video reference for the set, with body animators also doing all of the hand animation. The facial animators were also responsible for animating the characters' eyes and ensuring all of the eyelines were correct."

For the facial work, the studio employs a straightforward Direct-Drive method for applying the motion capture to the rigs, with a corresponding animation node for each marker on the actor's face. "The animators have offset layers for each of these controls to allow for non-destructive animation over the top of the mocap," says McDonald.

"We don’t have any blendshapes or specific deformers for facial work, rather it's based on bone translations. There were also auxiliary joints that were driven by the main controls to help maintain volume and create mouth shapes. Great attention was placed on how the control nodes were weighted to the skin surface to make the faces feel solid and as real as possible."

McDonald notes that while Direct-Drive rigs have a tendency to feel less solid and so inevitably require extra attention, the payoff is that they replicate all the 'fleshiness' of the captured face for free. "It's effective for characters based on scans and capture data from real people, in our case we were fortunate enough to be working with world-class actors."

Dynamically animated elements also contribute greatly to the sense of realism with the character in Beyond: Two Souls. Havok Cloth was chosen to handle these real-time dynamics. "It's a layer over Maya and not very user-friendly, but we have developed a very helpful PS3 Debug menu, which gives us rapid feedback and greatly improves this iterative process," says Brusseaux.

The system allows the artists to call up specific physics states for cloth meshes and hair during any scene. "When a character walks, runs, sleeps, sits down, jumps, or falls there's a corresponding physics state," says Brusseaux. "But each state obviously only works with one specific mesh, and we have 60 variations of the main character alone."

High-fidelity rendering

Underpinning all the skilful translation of high-quality acting into a real-time, interactive game world is a brand-new engine developed in-house by Quantic Dream. This allows for around twice the number of polygons and more complete use of the capture data (Quantic previously estimated that only 50 to 60 per cent of the recorded performance data was utilised in its previous title, Heavy Rain, for which the audio was also recorded separately).

"After Heavy Rain we really felt our engine had reached its limits on the PS3," says chief technology officer Damien Castelltort. "Unlike Heavy Rain's forward rendering engine, Beyond's offers full high-definition rendering, something that's really not that common on this current console generation."

Castelltort says that they moved a lot of processing over to the PS3's Synergistic Processing Unit in order to reach the performance targets they needed to deliver the desired graphical fidelity for Beyond: Two Souls: "All post-processing, such as depth of field, motion blur, bloom, and stars are now done on the SPU. This then allows us to remove some processing from the RSX GPU and to rework our shading model to obtain something more realistic. We call these our physically based shaders - they allow us to obtain a better lighting on the specular component of the materials."

In fact the shaders used in the game, including a completely reworked skin shader, were created to approximate the more ambitious shading model created for the studio's PlayStation 4 technology demo, The Dark Sorcerer.

"We also had to massively improve our texture streaming system to sustain everything that is happening on screen at any given moment," adds Castelltort. "The main characters use about 25Mb of textures each when seen up close, and sometimes there are several of them on the screen at the same time, while most of the sets use about 100/150Mb of VRAM in their highest-quality setting on top of that. The system has to balance it all to keep the visual quality at its best."

Stepping up the game

Given how far Quantic Dream has been able to advance PS3 graphical technology with the creation of Beyond: Two Souls, many are eager to discover what the studio has planned for Sony's next-gen console. Guillaume is cagey, but does confirm that the Dark Sorcerer prototype gives a firm indication of the technical advances and techniques they’re currently working on with the PS4.

"Some of the things we expect to be pioneering include more realistic skin shaders, improved dynamic lighting, complex cloth and hair sim, plus high-end performance capture and facial expressions," he reveals.

The tech in The Dark Sorcerer only hints at what the studio will be able to deliver later on: "When we created The Casting tech demo at the beginning of the PS3 cycle, we couldn’t imagine that Heavy Rain, our Kara demo and Beyond could push the limits of what is possible on that console so far. Who knows what we’re going to achieve on PS4?"

Words: Mark Ramshaw

This article originally appeared in 3D World issue 177.

Thank you for reading 5 articles this month* Join now for unlimited access

Enjoy your first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

*Read 5 free articles per month without a subscription

Join now for unlimited access

Try first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

The Creative Bloq team is made up of a group of design fans, and has changed and evolved since Creative Bloq began back in 2012. The current website team consists of eight full-time members of staff: Editor Georgia Coggan, Deputy Editor Rosie Hilder, Ecommerce Editor Beren Neale, Senior News Editor Daniel Piper, Editor, Digital Art and 3D Ian Dean, Tech Reviews Editor Erlingur Einarsson, Ecommerce Writer Beth Nicholls and Staff Writer Natalie Fear, as well as a roster of freelancers from around the world. The ImagineFX magazine team also pitch in, ensuring that content from leading digital art publication ImagineFX is represented on Creative Bloq.