How Jurassic Park made cinematic history

From 19th-century statues to 3D-stereo depictions, our desire to walk with dinosaurs has led us to push the boundaries of art and science.

Cinematic history was made in the summer of 1993. Not only did Steven Spielberg's Jurassic Park usher in the annual summer blockbuster – with action films increasingly dependent on CGI – it also changed the way people thought about dinosaurs.

Once cinema goers had seen the terrified Lex and Tim Murphy narrowly survive a game of cat and mouse with two velociraptors, and Dr Alan Grant goad a hungry T-Rex with a flare, dinosaurs had entered the public's collective conscience as fully fleshed creatures, claiming their place amongst the greatest of movie monsters.

It would take some time before Spielberg's depiction of dinosaurs was bettered. Though informed by experts and blending the animatronic wizardry of Stan Winston and post-production stop-motion of Phil Tippett, it was the CGI skills of Dennis Muren that marked the film as a true innovator, producing the first fully realised digital creatures in cinema. But it wasn't the first time the archaic beasts had amazed people in 3D. In fact, for all its industry-changing visual technology, Jurassic Park owed a debt to a lump of Victorian concrete.

Learning from the past

In the summer of 1854 sculptor Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins unveiled 15 life-size dinosaur sculptures in London's Crystal Palace Park. His iguanodon, probably the most impressive sculpture due to its size, may resemble an over-sized lizard to the modern eye, but at the time Benjamin's Crystal Palace dinosaurs sent ripples around the world, shaping the look of fantastical movie monsters such as Ishiro Honda's Godzilla some 100 years later.

"To be fair, what the artist came up with was a perfectly reasonable model that was only found to be wrong around 20 years later," says Natural History Museum's head of the Vertebrates and Anthropology Palaeobiology Division Paul Barrett, "and then realised to be very wrong about 30 years after that." Working without the benefit of complete skeletons, Benjamin actually got a lot of the details right, like the fact that the legs are tucked underneath the body like an elephant.

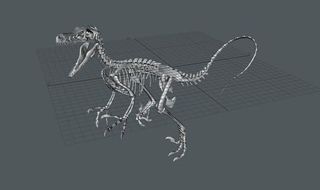

From Crystal Palace to Jurassic Park – and the next step forward to the fully CGI critters of the BBC TV series Walking with Dinosaurs in 1999 – palaeontologists have played a part in dinosaur depictions. The concrete creatures may have been set to squiffy data, but the show-stealing theropods (T-rex and velociraptor) in Spielberg's classic came with the latest theories tucked under their wings.

"Though the link with birds had been made already, Jurassic Park was one of the first times that it dictated how the animals would look," says Paul. "The result was jerkier movement and instead of a tail dragging along the floor, the theropods had a backbone held horizontally instead of upright."

Get the Creative Bloq Newsletter

Daily design news, reviews, how-tos and more, as picked by the editors.

This news just in

As of the beginning of 2014, the most up-to-date depiction of dinosaurs can be found in David Attenborough's Natural History Museum Alive 3D. Produced by Sky, it features the avuncular presenter staying in the NHM after hours as the life-challenged inmates breathe again. It's science disguised in the colourful clothes of entertainment.

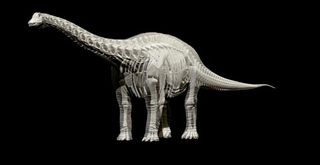

"This is the most scientifically informed film on the subject," says VFX supervisor James Prosser. "We had a world-leading expert for every creature we produced." And they produced plenty – from resurrecting the diplodocus in the main NHM hall, to animating a dodo (more svelte and nippier than previously thought) to a mastodon. It's also filmed in stereoscopic 3D at 4K resolution.

"This brings challenges for the CGI," understates James. In a nutshell, filming in 3D means depicting a greater sense of form and, "there are less cheats in stereo." Because it's 4K, "there's more resolution so the textures and the look of the creatures have to hold up against showing it in the iMax." James's team principally used Maya, with Mudbox and ZBrush for the modelling, Mari for the texturing, and some proprietary tools for the feathers and the fur.

Bedroom studios

The toolset has come a long way in the last 10 years, making a significant difference to what smaller companies can achieve on a limited budget. More than that, there are armies of dinosaur fans upgrading passionate personal illustrations into freelance jobs. The work of 3D creatives like Damir G Martin is a case in point.

"I remember creating a model of carnotaurus. I kind of evolved as a 3D artist with that dinosaur," he says. Impressed by David Krentz's design of the same dinosaur in Disney’s film Dinosaur (2000), Damir was compelled to try his hand at the little fellow. "I failed," he admits. "I failed a couple of times. I think I modelled it around 10 times before it looked cool." He's since worked on the Dino Dan children's TV show, with his work reviewed and approved by experts from the Royal Tyrrell Museum in Canada.

Manuel Bejarano is another fanboy and amateur-turned-pro: he taught himself 3D on free software OpenFX. With a glut of fossil discoveries in China, many dinosaurs are now thought to have had feathers, "but there has been a recent discovery that may change how we see dinosaurs now," says Manuel. "The duck-billed dinosaur edmontosaur found in Alberta has a fleshy crest on its head. It's important because reconstructions usually just cover the bones with skin, especially the head."

Just imagine trying to reconstruct an elephant without knowing where its trunk and ears went. "It would look like an alien," Manuel says. "That's why this discovery is so important; it opens up a world of possibilities." These possibilities include artistic licence. Not all the facts are in on dinosaurs, so artists have a role to play.

Discovery is so important; it opens up a world of possibilities

"Palaeoart is full of space for creativity," says CG character artist Vlad Konstantinov. Just take a look at two artists' representations of the same creature. "You are free to use various artistic styles or current hypotheses, you can observe modern life and use these hints in your work, or use a bit of fantasy. There’s only one main rule," he says, "and that is: 'don’t be in conflict with modern data.'"

Keep to that rule, and you could be seeing your creation spring up before you – literally, in the case of 3D printing. Manuel has already taken to printing models for customers. "Every dino has its own challenge, but the stegosaurus is particularly tricky," he says. "It has a beautiful design with all its plates along the back and spikes on the tail – it’s a lot of work rigging those plates to create different poses."

Print off the past

Raised by a palaeontologist, it seemed natural for CG artist Jet Cooper to be intrigued by dinosaurs. Today Jet works as a 3D supervisor at Propshop Pinewood Studios, and gets to create dinosaurs for a living. Other than satisfying the fan within, this is great for two reasons:

"The idea is to demonstrate the accuracy of both 3D modelling and scanning fossilised remains for 3D printing display pieces for the public to view, while expensive and rare originals are protected," explains Jet.

With damaged fossils being the norm, this solves a problem in the art of constructing ever-increasingly accurate dinosaurs for museums and films, and could save the industries money too.

"3D printing dinosaurs is simply cost effective when compared to traditional methods," says Jet. "Skeletons that are in the digital realm can be printed at any size and easily modified to produce male or female, or adolescent specimens."

Jet and his team at the Propshop have been practising what they preach for a good few years now. "We’ve adapted 3D modelling for the purpose of 3D printing to cater for the ever-demanding needs of the entertainment industry," he reveals, "and we’ve been printing a lot of what you see on the big screen over the last few years, from ships to weapons – absolutely everything!"

That's entertainment

Last year’s Walking with Dinosaurs is the last big budget film to star dinosaurs as the main characters. The film was developed from the Framestore fuelled dinosaurs of the BBC TV series of the same name.

"The first dinosaur I worked on was in early 1997 for the TV series," says Framestore's Daren Horley. "It was an arctic dwarf allosaurus, and at that point in time the project was still a bit of an experiment. No one on the team had any real experience in creature visual effects."

The series was a breakthrough in dinosaur depiction – showing the fully CG beasts and redefining what could be done – yet by today's standards, it may seem a little crude, based as it is on non-specular maps and just the one texture tile.

"Nowadays the texture tiles number a minimum of twenty 8K, probably a lot more," says Daren. "The geometry will contain displacement maps for every minute scale; the muscle simulation is at a level way beyond the technology available in the 1990s. The scrutiny and reworking, and polishing in a modern film means the asset build time will be many months. In 1997 it was two weeks!"

Daren has also indulged his love for dinosaurs in the series Dinotopia, based on artist James Gurney's book series of the same name. For this project he painted texture maps in 2D with Photoshop, projecting the images onto the geometry with Maya.

With today's pros using dedicated 3D paint apps like Mari and ZBrush, not to mention proprietary software that focuses on an element like feathers, the characters in big budget films are more prepared for a closeup. "Previously animatronic puppets took care of closeup shots, but now models can take any level of scrutiny."

Daren has gone on to create monsters for films such as 47 Ronin, but whether fondly recalling the tech limitations of the day, or creating a monster with a visible heartbeat, he still goes to work each day for the same reason.

"Seeing Jurassic Park made me realise that my destiny was in digital. The mesozoic era was familiar – a lot of the flora was the same, but the fauna was totally alien. The earth we walk on today must have been an incredible place back then," he says. "Maybe the allure is that it's all real. Five-ton, dagger-toothed, two-legged, upright predators. Scaly, feathery, and scary as hell. It's beyond anything science fiction has imagined."

This article originally appeared in 3D World issue 182.

Thank you for reading 5 articles this month* Join now for unlimited access

Enjoy your first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

*Read 5 free articles per month without a subscription

Join now for unlimited access

Try first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

Beren has worked on creative titles at Future Publishing for over 13 years. Cutting his teeth as Staff Writer on the digital art magazine ImagineFX, he moved on to edit several creative titles, and is currently the Ecommerce Editor on the most effective creative website in the world. When he's not testing and reviewing the best ergonomic office chairs, phones, laptops, TVs, monitors and various types of storage, he can be found finding and comparing the best deals on the tech that creatives value the most.

Related articles

-

-

-

-