How to create a cool 3D motorcycle

Digital artist Josh Flores explains how to create an accurate rendition of a Confederate Wraith motorcycle by mixing organic and hard surface modelling techniques.

Vehicle modelling can be a difficult task, but in this tutorial, I'll take you through the steps you need to build your very own Confederate Wraith B91 bike. During the course of the tutorial, you'll discover that there are different ways to build organic and hard surface models.

I'll also cover the importance of clean-up – so that the model can be used in production – as well as show you three paint methods I use to decal and colour the bike.

Typically I build a model by slowly detailing it piece by piece. The most important thing to think about when you start to model is blocking in the correct shape. Proportions and silhouetting is everything in the real world, this is why the block-in stage should be first, and should always be carried out with due care.

Once the block-in is set, tight and in the correct proportion, sculpting and detailing the model becomes a breeze. It doesn’t matter how much post-production a model goes through, if it’s the wrong size and shape, you can’t do much about it. So, in order to block in the model correctly you will need to do some research first.

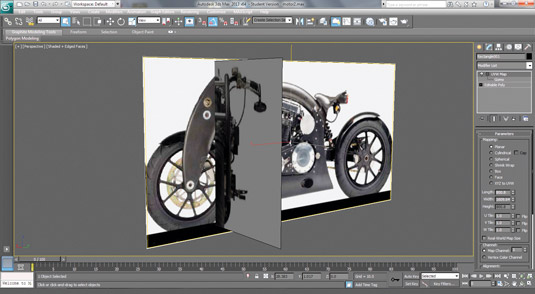

01. Create a blueprint

I collect various images of the bike from different angles and compile a front and side view by placing them in 3ds Max later. Most vehicle manufacturers and designers provide front, back and side orthographic views of the model in blueprint format.

This was not the case for the Wraith – I couldn't find a back view. It didn’t really matter though, as I simply looked for references of similar bikes and took their back views as reference.

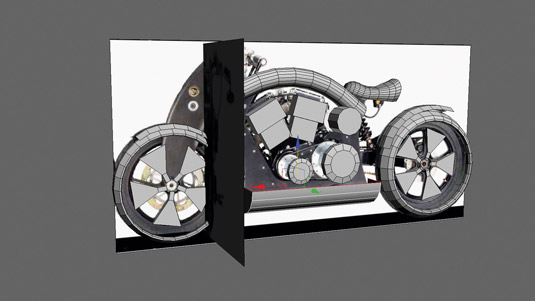

02. Block-in the model

It is fundamental that you get the proportions correct at this blocking-in stage (as we'll be moving onto the sculpting and detailing phase next, there won't be the opportunity to fix any issues).

Get the Creative Bloq Newsletter

Daily design news, reviews, how-tos and more, as picked by the editors.

First begin by blocking-in with simple primitive shapes, and also use splines for areas which have an organic flow to them. There is no detailing here, only edges and vertex have been added to match each silhouette shape.

03. Primitives and splines

My workflow revolves around using both editable poly shapes and splines to construct my objects. I tend to use splines mostly for organic shapes like the forks, because of the curvature. The bike frame and similar objects are built with a primitive cylinder.

I always find it best to start with a solid base first and begin cutting from there. The simpler you can make things, the easier they will always be to get right.

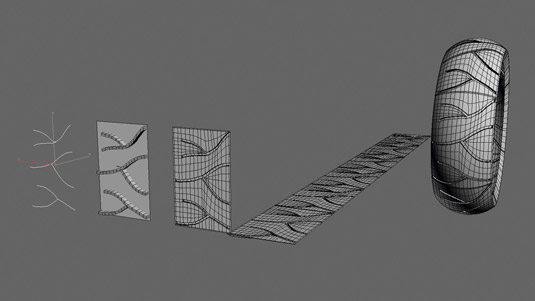

04. Organic detailing

ZBrush could be used to do the organic modelling, like sculpting the treads on the tyres, for example, but 3ds Max has some great tools that achieve the same result. Here use spline paths to build the various sizes of the twig-like shape treads.

Next use a Boolean operation to create a compound object, so that the tyre print is cut out off the plane. Finally, make sure the edges are spaced evenly so that the wrap is smooth when you use the bend modifiers.

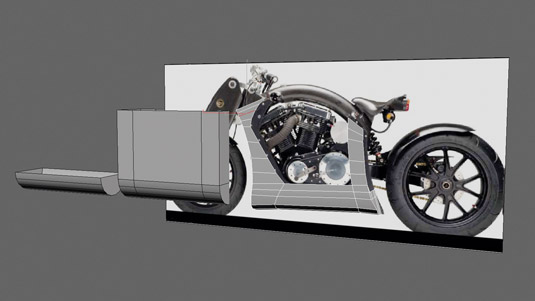

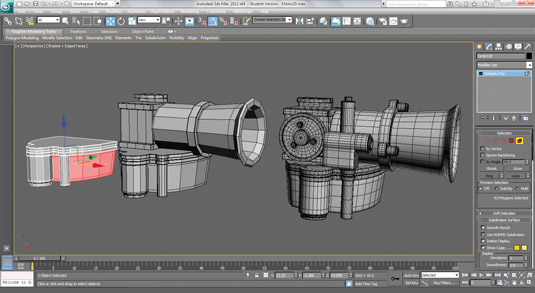

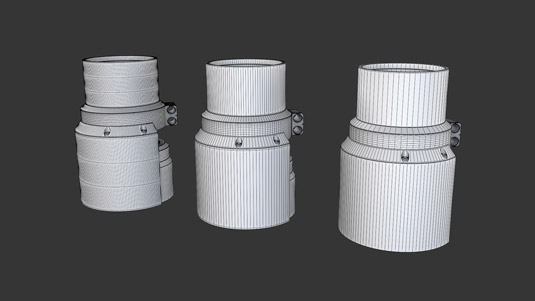

05. Hard surface flow

For certain tasks organic modelling is best, and hard surface modelling is better for others. Hard surface modelling is usually used for building more mechanical shapes with hard edges, extruded surfaces and functional details.

To create this piece of the muffler, use splines and extrude downward. To build the horn shape, use a circle and convert it to an editable poly. Lastly, create the attachments using cylinders and extruded faces.

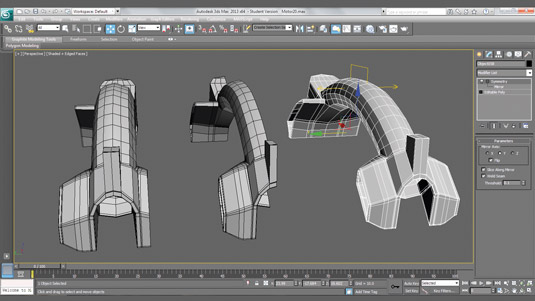

06. The symmetry modifier

It would be very time consuming to build every side of every object, and this is where the symmetry modifier can help. Before cutting the object in half and applying this modifier, make sure that your pivot point is dead centre.

Centring this makes the x, y or z axes even, to make a cut for the symmetry modifier to work. Now all that is left to do is finish detailing one side and mirror it.

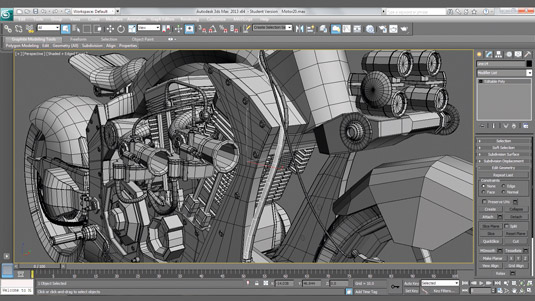

07. Add small details

Now that the bigger objects are finished and detailed, we can focus on the small details, these include bolts, rivets, cables and wires. These bolts and rivets are built in the same way as the hard surface shapes, by using primitive boxes and cylinders.

For wires and cables that wrap around the bike's motor and handles, create a spline path, with Enable To Viewport And Renderer set to On from the Rendering sub-menu.

08. Create clean topology

To finish the model, a double check on proportions and topology is needed before adding in a smooth modifier. Having a nice, clean topology flow will be helpful in keeping all the organic shapes smooth. Just the slightest uneven polygon surface can cause an ugly pinch or bump.

To edit these and move our vertex evenly along an edge, the best tool to use is the Vertex Edge Constraint found in the Editable Poly menu under Edit Geometry.

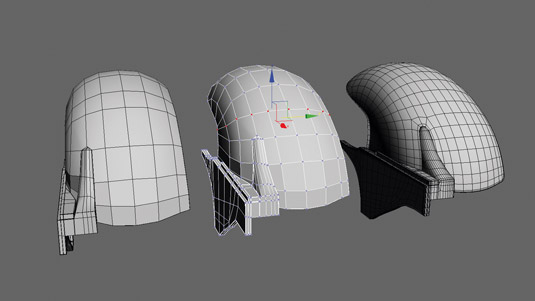

09. Collapse and clean-up

The bike is now ready to be completely smoothed out and cleaned up. To do this, apply a MeshSmooth modifier and collapse the stack to finalise the bike model. This model is a now a high-poly model, but it is not yet ready for rendering.

We want to do all we can to bring down the render time, so delete any extra geometry. Extra geometry will mostly be found around areas where locking loops are applied, such as in corners.

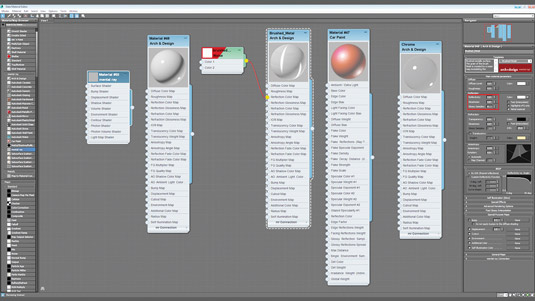

10. Mental Ray materials

Using the Slate Material Editor is a great starting off point to begin painting. What is great about using mental ray renders is its vast library of metal materials and the Arch & Design material. Use the chrome and brushed metal materials for the bike.

Plastics and car paint material would also be great to use here. The materials are good, but just a little tweaking in the Material Parameters can make them look like convincing, real-world surfaces.

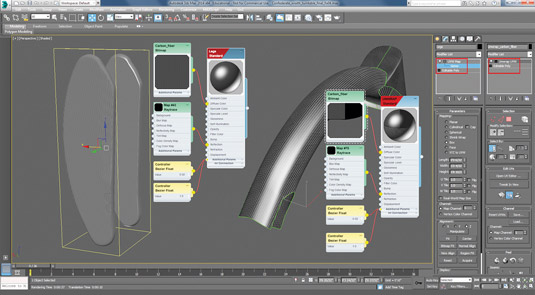

11. Use a UVW map modifier

I also like to apply textures using a UVW map modifier. For example, I apply the UVW map modifier to objects like the forks. Since the shape of the forks is flat, applying a UVW coordinate creates a map to which I can apply a carbon fibre image bitmap.

For other objects that aren't so easy to apply coordinates to, a UVW unwrap modifier could be applied. The map can now be taken into Photoshop for painting and texturing.

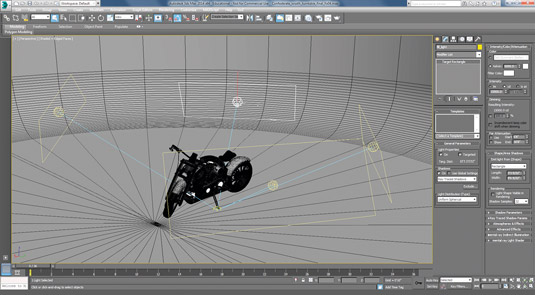

12. Setting the stage

My models are usually set around a traditional three- point light setup, but here I add more lights to direct attention to certain areas on the bike. Since we are using mental ray, I opt to use photometric lights, which does its best to replicate real-world lighting.

For the shadows, apply ray-traced shadows and for intensity, choose Kelvin scale. Not only do these two settings give nice soft shadows, but they also make the room look like it’s a cool temperature.

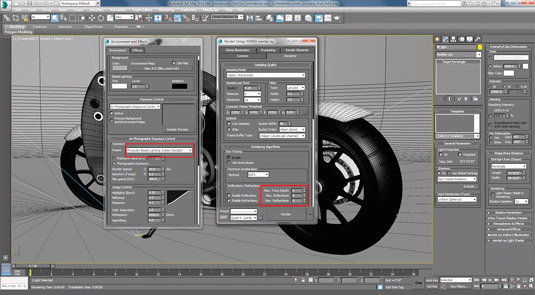

13. Final render settings

Since the bike is mostly composed of metal materials, set the glossy reflections and refractions quite high. Render time might take a little longer, but the metals will have nice reflectivity. Another setting that I experiment with to get good results is Exposure Control.

Here I can apply an HDR image to the bike's surrounding; and much like real-world cameras, I can also apply an exposure preset for image control.

14. Final composite

Now we're ready to render out the bike in HD format and also render a few passes for compositing purposes. Don't just render out of 3ds Max: Tight and wide ambient occlusion renders help to bring out the shadows on the bike.

Rendering an RGB mask channel helps in the selecting of certain parts on the bike for colour correcting or lighting. Lastly, a z-depth pass is rendered out for focus. Composite these all together and your bike image is finished.

Words: Josh Flores

Josh Flores is skilled in low and high poly modelling, and his Confederate Wraith motorcycle was built using organic modelling and hard surface skills. This article originally appeared in 3D World issue 181.

Thank you for reading 5 articles this month* Join now for unlimited access

Enjoy your first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

*Read 5 free articles per month without a subscription

Join now for unlimited access

Try first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

The Creative Bloq team is made up of a group of design fans, and has changed and evolved since Creative Bloq began back in 2012. The current website team consists of eight full-time members of staff: Editor Georgia Coggan, Deputy Editor Rosie Hilder, Ecommerce Editor Beren Neale, Senior News Editor Daniel Piper, Editor, Digital Art and 3D Ian Dean, Tech Reviews Editor Erlingur Einarsson, Ecommerce Writer Beth Nicholls and Staff Writer Natalie Fear, as well as a roster of freelancers from around the world. The ImagineFX magazine team also pitch in, ensuring that content from leading digital art publication ImagineFX is represented on Creative Bloq.