Between heaven and earth: behind the scenes of Elysium

VFX studio Image Engine reveals how it crafted heaven and earth for the sci-fi blockbuster.

It's been four years since VFX industry poster boy turned directorial wünderkind Neill Blomkamp showed his mainstream mettle with District-9, a science fiction action movie so riotous, intelligent and original it left many heralding him as the new James Cameron. Pretty impressive, given that a mere three years before that he was just gaining fame for turning a Citroën into a dancing robot.

Now comes his sophomore effort, another futuristic tale with a strong socio-political subtext and effects courtesy of Image Engine, but this time with a budget estimated (at $98 million) to be three times that of its predecessor.

Given the director's close working relationship with Image Engine, and the fact District-9 actually signalled its entry into the world of high-end film effects, it's not so surprising that some people assume Blomkamp has a stake in the studio.

"The simple fact is that we both live in the same town and like working with each other," says Andrew Chapman, second unit supervisor and then associate visual effects supervisor on Elysium. "Peter Muzyers (visual effects supervisor for the production) started talking with Neil about Elysium during District-9. I think Image Engine was the obvioius choice for us to pursue for this project."

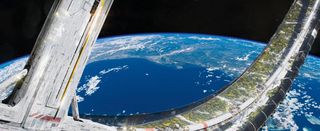

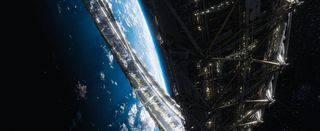

As with District-9, Weta Workshop also contributed to the project. Not only were they involved in crafting the physical props but also providing designs for many assets that would ultimately be created digitally. Blomkamp also brought in legendary design Syd Mead in to help with the design of the movie's titular environment: a spoked torus spacestation orbiting the Earth, that provides home to the privileged few, while the rest of humanity lives in squalor on the ruined planet below.

Nevertheless, Chapman admits the design still needed much work by the time principal photography began. "The problem was the sheer scale of design work required. A ring hovering in the sky is pretty straightforward, but once you get into shots with vehicles flying over the rim and descending onto the surface, you find you need to design down and down."

Chapman says they continued chipping away at the Elysium ring throughout the shoot, and then really began to push things forward once they had the director's full attention. "Visual effects supervisor Peter Muyzers set up an in-house art department at Image Engine to take on the monumental design challenge.

The ring really was a monumental design exercise

"We ended up with some things taken from Syd, others from Weta, some directly from Neill, and then the rest from our concept artists Kent Matheson, Mitchell Stuart, and Ravi Bansal. It really was a monumental design exercise. We needed to make sure it was just right before we could even start constructing it. If we had gone off prematurely on the wrong path it would have been such a huge build to modify."

Chapman says the scale of the ring - 125 kilometre circumference - was defined by Neill's idea of how many people would be living there and how much land each member of this elite class would likely have: "We looked at photo reference of crazy mansions of the super-rich to get an idea of space, and then worked out the scale from that.

"We did technical previz - one of our guys was really geeking out about its distance from earth and required orbit - but the overall driver was aesthetic, with the aim to have it in the sky four-to-six times the size of the moon. We were also particularly mindful that you needed to be able to relate to humans having built this thing. We didn't want it so large that people couldn't connect the dots."

The aim was to have it in the sky four-to-six times the size of the moon

Chapman says they looked at real world mansions when designing their own to scatter across the ring world. "We didn't go so far as to utilise photogrammetry, but they were a big influence. It's difficult to say how many unique buildings we ultimately created, as we used a modular system. It wasn't anything like a CityEngine type approach, as we still needed manual control, but our helper tools did allow us to procedurally scatter elements, and to grab the garage from one and the east wing of another to make something new, for example."

Heavy scenes

The more demanding scenes of the Elysium ring ultimately ended up containing more than three trillion polygons. To make the modelling of such a complex environment feasible, Image Engine made smart use of instancing. One fifth of the ring was done as a complete build, and then instanced around the inner circumference. A few further modifications were added in to ensure that viewers wouldn't be able to spot any repeat of the designs or paterns that were used in the construction.

"As the design progressed we also decided to partner up with San Rafael-based Whiskytree, so that we could focus on the hard surface work and have them provide the terrain dressing," explains Chapman. "They effectively became like our inner surface environment department, building bespoke layouts as well as performing the same sort of instancing tricks over the top."

One key difference between Elysium and District-9 is that on this project Image Engine managed the effects for the show from a central hub with Shawn Walsh as overall VFX producer. In addition to handling around 70 per cent of the 1,000 shots (822 of which made to the final cut), the studio also selected and supervised several other vendors including Method, MPC, Embassy VFX, ILM and the aforementioned Whiskytree.

"We recognised that the main thing Image Engine could bring to this project was our close collaboration with Neill and the ability to manage the project, and if that meant some of the work had to go outside - we recognised that as a necessary part of taking on something so big," says Chapman.

With the Elysium ring by and large a digitally created affair, Blomkamp contrasts this pristine environment with far grittier and more naturalistic scenes down on planet Earth. "The genius move Neill had was finding locations that gave him what he needed right in-camera," says Chapman. "After shooting on sound stages and in nice mansions around Vancouver production relocated to Mexico City, shooting in favelas and what turned out to be the world's second largest landfill site. It was a pretty depressing environment, and after a toxicity report they even had to ship in clean dirt, but it was worth it because right off the bat the plate photography looked amazing."

The genius move Neill had was finding locations that gave him what he needed right in-camera

Image Engine was tasked with turning this into a horrific vision of a future Los Angeles, adding in a modified version of the real city's skyline. Access to official plans for all approved building work

in LA for the next couple of decades helped lend these enhancements an air of authenticity. "Neill also modelled one of the new buildings himself, using Lightwave," says Chapman. "It was interesting to have a director building a model for us, but with his background he simply found it quicker and easier to do it by hand."

Slim droid design

While environment work is fresh territory for Image Engine, the studio was able to tap into its creature expertise for the creation of the various types of droids that populate the movie. As with the aliens in District-9, these were created using quite a complicated hybrid capture/ animation approach.

Stunt performers wore marker-covered grey suits on set, with witness cameras in addition to the main one on hand to over all the angles. In post, the Image Engine artists then performed a first pass by manually matched model animation to the original performances. These roughs would either then be approved or notes would be given on how to finesse or deviate from the original performances.

Chapman reveals that they started to investigate writing tools to automate the whole tracking process, but found that the animators would turn shots around so quickly - typically within a couple of days - that the R&D effort was deemed unnecessary. "And besides," he notes, "there was inevitably always a need for some additional animation work, even with detailed tracking data to hand."

Chapman says their hybrid approach was ideal for a number of reasons. "Obviously it gave us great reference for lighting and performance, but it also meant that they could edit scenes ahead of the visual effects process, which in turn meant that once we began work on a shot there was a clear path to getting approval and our work was unlikely to end up on the cutting room floor. Neill even went so far as doing more takes if stunt guys didn't hit their marks. They wondered why, given that we were going to be replacing them, but it was important to get as much as possible in camera as the basis for our work."

While painting out the performance reference had been quite an arduous task on District-9, the design of the droids covered up the performers on the live plates. Or at least that was the intention. "Unfortunately when they went through a redesign we ate into their profile a bit more," says Chapman. "Neill wanted them less like American football players and more Special Forces soldiers, so we added more gadgetry and slimmed them down a bit.

"The problem was that we hadn't expected painting to be an issue, so we hadn't shot many clean plates. But then, even when you do have plates to work with it's really only a helper, it's not like you can just slot stuff right in."

As with the Elysium ring, the aim with the droid designs was to give them functionality and plausibility. Car panelling and military hardware provided some reference, while the springs at base of the droids' backs directly mirrors those used on motorcycles. "All the pistons and fine detailing actually matches to real-world reference,” says Chapman. "Even though you're dealing with a big walking, talking droid, all the building blocks are designed to look and feel familiar."

All the pistons and fine detailing actually matches to real-world reference

Getting a model that looked workable while still matching up hard surface geometry to human performances was certainly something of a challenge, admits Chapman. "One simple trick we used to fit the stunt performers with chest packs to constrain their arms. And then, because the droids are composed of so many intricate pieces of geometry, we were able to push things around a little bit to avoid intersections. The final model was incredibly complex.

"If you tried looking at a wire-frame you'd just see a solid blue shape. Every single element went through so much scrutiny, with a lot of time spent on every single scratch, piece of paintwork and decal - it was crazy."

Such attention to detail has paid off, providing Elysium with a perfectly photoreal army of digital soldiers and incredible landscape shots.

Words: Mark Ramshaw

This article originally appeared in 3D World issue 174.

Liked this? Read these!

- Create a perfect mood board with these pro tips

- The best 3D movies of 2013

- Download free textures: high resolution and ready to use now

Thank you for reading 5 articles this month* Join now for unlimited access

Enjoy your first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

*Read 5 free articles per month without a subscription

Join now for unlimited access

Try first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

Get the Creative Bloq Newsletter

Daily design news, reviews, how-tos and more, as picked by the editors.

The Creative Bloq team is made up of a group of design fans, and has changed and evolved since Creative Bloq began back in 2012. The current website team consists of eight full-time members of staff: Editor Georgia Coggan, Deputy Editor Rosie Hilder, Ecommerce Editor Beren Neale, Senior News Editor Daniel Piper, Editor, Digital Art and 3D Ian Dean, Tech Reviews Editor Erlingur Einarsson and Ecommerce Writer Beth Nicholls and Staff Writer Natalie Fear, as well as a roster of freelancers from around the world. The 3D World and ImagineFX magazine teams also pitch in, ensuring that content from 3D World and ImagineFX is represented on Creative Bloq.