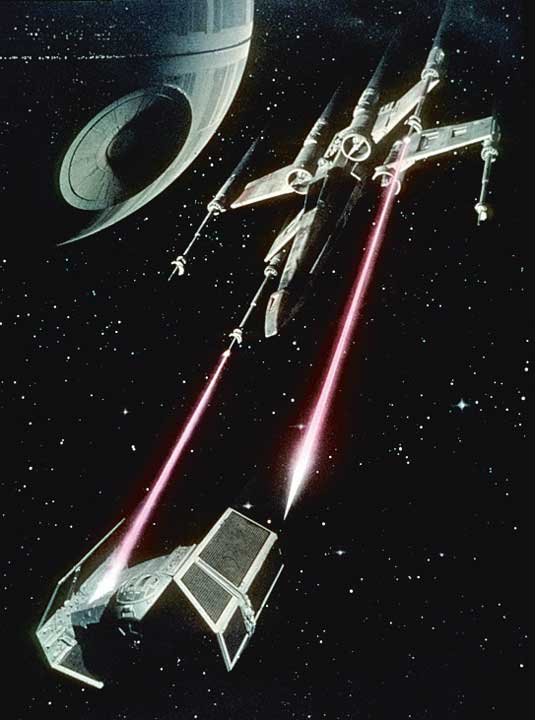

Secrets of the VFX studio behind Star Wars

As the world gears up for the new Star Wars film, we chat to the VFX wizards at ILM about 40 years of magical effects.

One of the biggest 3D movies of 2015, the seventh Star Wars film is scheduled for release this Thursday, and it's sure to be packed with amazing effects, courtesy of Industrial Light & Magic (ILM). It's a fitting end to a year in which the studio has been celebrating an astonishing 40 years in the business.

ILM began with a handful of people hired by George Lucas to create visual effects for the first Star Wars, which was released in 1977. Today, ILM is a thriving global studio with 1,200 people in San Francisco, Singapore, Vancouver and London.

Of course, the studio has much more to its credit than Star Wars. Films with effects created at ILM have won 16 Oscars, and received 33 Oscar nominations for best VFX. And, of the top 10 all-time worldwide box office hits, ILM has worked on half of them Avatar, Titanic, The Avengers, Iron Man 3, and Transformers: Dark of the Moon.

Equally important, the artistry in VFX for those films and many others can be traced back to inventions and innovations created by people at ILM during the past 40 years, and to the early application of CG techniques for production filmmaking.

"I think there is really something valid about the influence we've had on films," says senior visual effects supervisor Dennis Muren. "The techniques we've brought to filmmaking have opened up the medium to telling stories that couldn't have been told before. I think you see it all the way through."

1970s: the beginning

When Dennis Muren joined ILM in April 1976, he witnessed the studio's first innovation in visual effects. "It was before any shooting had been done [on Star Wars]," he says. "They were still building the shop. I'd never seen anything like it. Everyone was so young – my age and younger – and everything was under one roof.

"The approach John [Dykstra] had taken with motion control was to break everything into separate elements, each shot separately programmed with motion control gear, so they all had their own flight path. Then we'd composite them together. It was so complicated that it was great to have everything in one place. It was very unusual for a Hollywood film."

Get the Creative Bloq Newsletter

Daily design news, reviews, how-tos and more, as picked by the editors.

The main challenge back then was ensuring everything was precise. "The film had to go through perfectly without any shaking and only a couple of places could fix gear to be that precise," Dennis says. "Models had to be made to precision. Explosions had to break apart realistically. It was a very linear process and if something didn't work we had to do that part again, often from scratch. We needed a lot of physical space and some equipment was literally dangerous."

In addition to bringing the VFX process all under one roof, Dennis exalts the in-house art department. "We've always had an art department," he explains. "Most studios would bring someone in, or expected the director or studios to provide shot design. To us, the art department seemed as necessary as a camera department.

"We have ideas a director or producer might not know are possible. So it gave us a way to get in early and that has been great. Now, not all shows that come in need [our shot designs], but every show still goes through our art department for the studio to consider our ideas before we start the show."

1980s: enter computer graphics

The advent of CG as a serious production tool transformed the whole industry, and that happened largely at ILM," says CCO John Knoll. "The big turning points were the Stained Glass Man [in Young Sherlock Holmes] - that was Lucasfilm's computer division - The Abyss, the first film with ILM's computer graphics; T2, which had a central character executed in CG; and Jurassic Park, which shocked the industry and marked the end of stop motion as a technique for doing creature work."

ILM hired Scott Farrar to shoot models at ILM for the 1982 film Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan. Little did Scott know that he'd also shoot the first entirely CG sequence in a film.

"The only way to photograph the CG effect was to set up a camera with an intervalometer to control the camera shutter," says Scott, who is now a senior VFX supervisor. "We put the camera on a tripod in front of the monitor and shot all night."

To shoot the star field, effects supervisor Jim Veilleux and Scott photographed a camera flying through a 3D array of stars at Evans & Sutherland, again using a camera on a tripod in front of the monitor. "I had a crew of about 60," Scott says. "On the last Transformers, I had between 300 and 400. The difference is staggering."

In 1985, the first photorealistic CG character, a knight made from stained glass, fell from a church window in The Young Sherlock Holmes and made film history. Dennis Muren was the VFX supervisor and received an Oscar nomination for that film.

In 1988, Doug Smythe and ILM's CG department worked with Tom Brigham to create the first morphing system for Willow, resulting in technical achievement award and another ILM VFX nomination.

In 1989, artists first applied a system developed at ILM for wire removal and for removing dirt and damage artifacts from film to help create Back to the Future II. "Bit by bit, we tried new things in movies," Scott says. "That's what ILM has always done – experimented. You can point to so many movies, so many little steps and advances that moved us forward."

1989 also brought to the screen James Cameron's The Abyss in which a transparent CG pseudopod made faces at Mary Elizabeth Mastrantonio. To help make that possible, John Knoll did what was probably the first set survey with CG in mind.

"It was all so new," reflects John. "I went along for the plate shoot, I figured that someone would need to measure where the camera was relative to landmarks on the set so we could match our CG cameras. I measured the set with a tape measure and drew where the camera was on Xeroxed floor plans.

"Then, as the pseudopod was reflective, I brought in a still camera and photographed full 360s around the set to stitch into reflection environments. We were making it up as we went along. Many of the procedures' basics are still the same."

The Abyss was a turning point for Dennis Muren: "After The Abyss, I thought 'I have to know this because I have to control it, I had a million things to learn and I took a year to study at my own pace. I wanted to get CG into production. Not just five shots."

1990s: CG gets serious

The T-1000 character from Terminator 2 that shape shifts from human form into liquid metal was the first CG character on film to have natural human motion, a widely acknowledged VFX breakthrough. But the film was also the first to use camera-projected plates for matte paintings.

"We developed it for the shots when the T2 [the T-1000] pushes through the bars of the jail," John says. "The idea is to take a live-action plate, project it onto CG geometry, and then when you warp the geometry, the image goes with it.

"We used it for matte paintings for the first time for Hook [in 1991]. We created Neverland as traditional paintings on glass, but then matched the camera and the basic shape of the island in CG with simple representative geometry, projected onto that geometry, and flew a camera toward it.

"The whole painting moved in perspective in a way we had never seen with 2D matte paintings. It was revolutionary. We used it for Mission Impossible [1996], and pretty soon itbecame an industry standard."

The 1993 film Jurassic Park followed shortly after T2, and signalled the real beginning of CG characters in films. "Those of us in the model shop were aware that there was only one miniature set used in Jurassic Park," says John Goodson, digital artist and model maker. "The Ford Explorer pushes over the wall. Usually, we did a significant amount of stuff. We thought, 'Wow. Something is changing.'"

With T2 and Jurassic Park, ILM had made CG an essential part of the films and showed the industry that CG was production ready. "We were no longer limited by materials, models, wires, gravity, physics," Dennis says. "We were making shots we could imagine. It was incredibly liberating. No one knew… that is, until they saw T2 and Jurassic. We could have gone ten years longer without knowing. But that nut was cracked here because we had filmmakers and scientists. Then the trick came in making it look real, not artificial.

The 1995 film Jumanji put CG hair and fur to the test, and resulted in an Academy technical achievement award. Casper, a second film that year, put a CG character into a starring role alongside actors.

"Suddenly, between Jurassic Park and Casper we had to quadruple the size of the animation department," Dennis says. "We couldn't find another 50 people who knew CG. It was one of several huge spurts where we had to get people in and train them in esoteric areas and give them schooling in the tools we have and the quality we expect."

In the 1990s, artists at ILM won Oscars for Terminator 2, Jurassic Park, and Forrest Gump, and received nine Academy Award nominations.

One of those nominations was for Backdraft, which marked the first use of the ILM Trilinear High Resolution CCD Digital Input Scanning system developed in partnership with Kodak. It scanned its last film in 1996: Mission Impossible. Backdraft was also the first film with ILM's CG fire. CG water flowed into the production line for the 1998 film Deep Impact.

"We learned how to make a wave with white caps that left little trails," Scott says. "We improved on that with Perfect Storm [in 2000] and those two films moved CG water forward. Now, we have the relationship with Stanford researchers for Physbam to do physical representations of natural things – dust, fire, water. But water is still hard."

2000s: the digital age

According to Dennis: "The industry exploded in 2000. It started with Phantom Menace [1999]. With that and Lord of the Rings [created at Weta Digital], CG visual effects became a way to make movies. Greenscreen or bluescreen, directors could imagine anything and get what they wanted. Audiences had never seen stories like that outside stop motion or cartoons. So, we needed to rise up to that scale. We had 1,200 people working on those prequels. It was massive."

With Episode I: The Phantom Menace, filmmaking became digital. "We've made great, big, important developments over the years, but there were also significant smaller innovations," says John Knoll, who was a VFX supervisor on EPI along with Dennis, Scott Squires, Scott Farrar and Barry Armour.

"For example, up until EPI, our matchmoving tools were largely manual for the most part. People were lining up things by eye, setting keyframes, and seeing where they slipped. Tracking features and using the camera to back solve happened with EPI. We hardly do a shot now without that being the first step."

Today the biggest challenge is differentiation and budgets. "There's so much on the screen now compared to 30 or 20 years ago, that a lot of the work looks the same," Dennis says. "The biggest problem is how to make it look different. Make it fit within the film and not stand out. That's the feeling I have. The work is overused.

"Studios think if you put in more effects, you'll make more money and in some cases, they're right. The problem is how to keep the quality of the imagery up, the price down and meet the deadlines.

"We have to compete with the financial realities of competing with overseas companies that pay less and get refunds and tax incentives. That's almost unsolvable by staying in California. So, we have the four studios. We need that."

Having a global presence and a capacity in tax-incented countries has allowed the studio to stay competitive. So, too, have the efforts of the R&D teams and artists who look for ways to make the process more efficient.

"The world of rebates is really hard," Scott says. "That's one reason why I'm trying to refine the tools, make them easier, quicker and moreefficient for artists to use."

"We're the last of the big American effects companies left," John says. "That's partly because we've gone international. And because we've always put a high premium on hiring the most talented people we can. Extremely experienced, talented people do things right the first time. That's how we get price competitive."

We can't wait to see the amazing film sequences the ILM artists will come up with over the next 40 years.

Liked this? Read these!

Thank you for reading 5 articles this month* Join now for unlimited access

Enjoy your first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

*Read 5 free articles per month without a subscription

Join now for unlimited access

Try first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

The Creative Bloq team is made up of a group of design fans, and has changed and evolved since Creative Bloq began back in 2012. The current website team consists of eight full-time members of staff: Editor Georgia Coggan, Deputy Editor Rosie Hilder, Ecommerce Editor Beren Neale, Senior News Editor Daniel Piper, Editor, Digital Art and 3D Ian Dean, Tech Reviews Editor Erlingur Einarsson, Ecommerce Writer Beth Nicholls and Staff Writer Natalie Fear, as well as a roster of freelancers from around the world. The ImagineFX magazine team also pitch in, ensuring that content from leading digital art publication ImagineFX is represented on Creative Bloq.