"We wanted to talk about AI and its relationship to art" – how we made 2025’s VES Student Award-winning animation Pittura

The annual Visual Effects Society Awards, announced on 11 February, celebrate the best VFX of the past year in film, TV, games, commercial and beyond. But one of its highlights is the award for Outstanding Visual Effects in a Student Project. Sponsored by Autodesk since its inception, the award throws a large spotlight on the stars of the future and does a good job of making the best 3D software and the best animation software accessible.

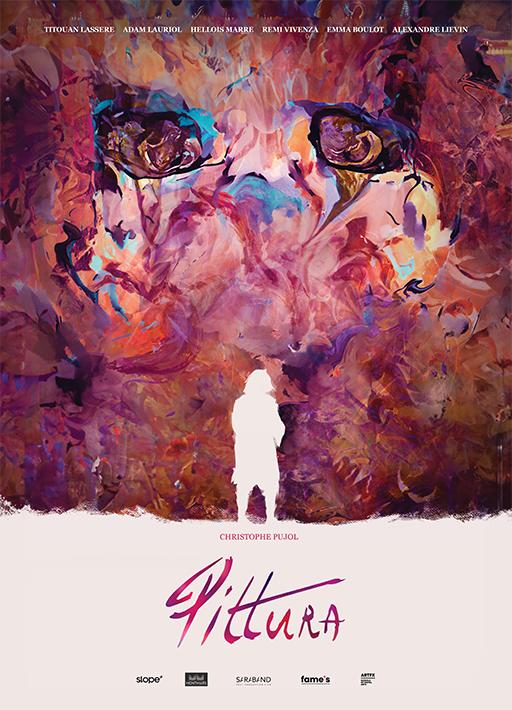

This year’s winners are the team behind Pittura, an ambitious and emotive short film exploring the relationship between humans and AI through the lens of art. Set in an alternative Renaissance period, Pittura brings together a talented painter fighting Parkinson’s disease and a robot striving towards a new level of personal expression. The effects work includes scenes that are sometimes epic, sometimes intimate and small.

Pittura was produced by a student team from ArtFX School of Digital Arts in France (the same school that also produced last year’s winner) – Emma Boulot, Titouan Lassere, Adam Lauriol, Alexandre Lievin, Hellois Marre and Rémi Vivenza. As part of our How We Made series, we asked Titouan to tell us about the development and production of Pittura, and how it feels to have scooped a VES Award.

Visit the VES Awards website to see more, but read on below to discover how these talented students made Pittura.

SPOILER ALERT: This interview includes a mild spoiler. We recommend watching the film first

CB: How did you develop the concept for the film of traditional art meeting AI?

Titouan Lassere: We started writing scenarios with the idea of a robot interacting with art, particularly painting, but tackling different themes and genres. It was only after many drafts that we realised that what we wanted to talk about was AI itself and its relationship to art. However, right from the start of the writing process, we had the idea of creating a memorable and original robot, detailed and complex, and a big city marked by the influence of art even in its streets.

CB: How important was pre-production for this project, and did you use any new software or workflows?

TL: Pre-production had to be done fairly quickly, due to time constraints, but it enabled us to test and experiment with techniques essential to our project, which redefined even the robot's design. We also spent a lot of time thinking about the film's different moods, as we wanted to create strong, evocative atmospheres. Adam did a lot of concept art to help define the colour script.

CB: What were the artistic influences that shaped the style of Pittura?

TL: There have been many influences on the development of Pittura, the main inspiration for the robot was Alita Battle Angel, and the city was inspired by Italian cities such as Venice, as well as Star Wars' Naboo. One of our more unexpected inspirations was Alejandro Jodorowsky, particularly his Dune project. We really wanted to reproduce his creative freedom in our colours for the last sequence, as well as the robot's paintwork.

CB: How did you balance the needs of the storytelling with the desire to push the technical execution?

TL: We first pushed our storyline around our theme before we even started designing anything, so that we could create our film according to what we wanted to tell. We developed all our art direction with the aim of bringing art face to face with our robot.

CB: What VFX techniques and software did you use?

TL: We decided to render on Houdini with Autodesk Arnold because we had a lot of elements directly on Houdini, like the procedural city, or the painting effects for example. [Read our best rendering software guide for more details.)

Despite our many shots, you'd think rendering would be particularly time-consuming, but we had mainly still images to render indoors, which meant we could render without worrying too much about optimisation.

We also used ZBrush and Autodesk Maya extensively to create the robot, one to model the outer shell of the robot and the other for the harder-surfaced interior. Autodesk Maya was particularly useful for the rig, and we then exported our animations to Alembic to render them in our Houdini scenes.

CB: Did you need to create a unique pipeline or work in a new way?

TL: As we were in a production situation, our class had two ITs (Elouan Rogliano and Angèle Sionneau) who were in charge of creating a pipeline, which enabled us to work properly with professional tools, to be monitored by our superiors and to render our farm without a hitch.

CB: What was the most complex shot you created?

TL: The most complicated shot in our film is probably the end shot, with the contact between the robot and the actor. Giving that feeling is always a tricky thing to approach. On top of that, this shot brought together all the elements: keying, lighting, the robot, paint FX… Being the last shot, we had no room for error.

To pull it off, there was no miracle cure or revolutionary technique, but above all meticulousness and preparation upstream on the shooting. The compositing of this shot had to be done with a lot of time to recover all the details of the actor's arm and make the contact credible.

CB: Were there any unique or experimental techniques you used for this film?

TL: The most experimental technique we used was to animate our robot's face. As we had no animators, we had to improvise. We used Live Link, which lets you motion-capture a face on an Apple device and transmit this data to Unreal Engine on a MetaHuman Character. We then exported the character's facial rig, and after cleaning it up, we bound it to our robot's face. This enabled us to play out all the robot's reactions ourselves. [Read how River End Games made use of MetaHuman Character too.]

CB: What lessons did you learn from this project?

TL: This project has taught us a lot, both humanly and artistically. Communication between all the members was essential, and we also saw the importance of being pragmatic and going for the essential. We had no time to fall behind. Films always need to be released and we always want to keep pushing them, so there are obviously things in our short film like FX, animation, compositing, and even shots that had to be cut out of feasibility.

CB: Finally, how does it feel to be a VES winner?

TL: Honestly, it's quite incredible. Even if we had created our group with the desire to win them, it was still an impossible dream, we were wrong. When we found out we'd won, it took us a long time to realise it, right up to the moment of the prize-giving. That's when you realise how lucky you are to work in this industry. To be surrounded by so many passionate, caring people... it's a magical feeling.

Daily design news, reviews, how-tos and more, as picked by the editors.

Richard is an editor and journalist covering technology, photography, design and illustration. He was previously editor at the magazines 3D World, Mobile Computer User and Practical Web Design, as well as deputy editor at Mac Format and commissioning editor at Imagine FX. He is the author of Simply Mac OS X.

- Ian DeanEditor, Digital Arts & 3D

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.