The making of Transformers

They’re 30-foot-high shapeshifters. They’re made out of thousands of moving parts. And they’re out to beat the living cogs out of one another. Transformers might have posed something of a problem for an average VFX studio. Fortunately, ILM is anything but average...

When Industrial Light & Magic began working on Michael Bay’s Transformers, the VFX crew thought they would be modelling three or four hero robots that might do 14 transformations. One year later, the team had assembled 60,217 vehicle parts and over 12.5 million polygons into 14 awesome automatons that smash each other, flip cars in the air, crash into buildings and generally cause enough mayhem to make even the most jaded moviegoer feel like a 10-year-old again.

To add tyre treads, dirt, scratches, colour and other textures, painters applied 34,215 texture maps to the parts. Animators and character developers transformed the robots 48 times, moving digital headlights, bumpers, engines, tailpipes, doors, gaskets, bolts, tyres, and other pieces to and from CG jets, cars, helicopters, trucks and other vehicles.

The animators and character technical directors crafted each transformation by hand, manipulating the machines by using 144,341 rigging nodes, and sent them into battle. If you haven’t already guessed, these aren’t the lovingly remembered TV cartoon robots. They’re 21st-century, giant, badass, big-screen fighting machines.

VFX supervisor Scott Farrar has a toy Optimus Prime on his desk at ILM, one of the original Autobots. It has 51 parts; he can hold it in his hand. The Optimus Prime that ILM created for Transformers has 10,108 parts and stands 28 feet tall.

Things have changed since Hasbro and Takara introduced the first Transformers toys in 1984. Since then, the robot aliens from the planet Cybertron that can disguise themselves by transforming into different types of vehicles have starred in comic books, video games, a television series, and an animated film.

But, until now, the huge robots have never fought their war on earth in a live-action film.

The movie stars Shia LaBeouf and Megan Fox as Sam and Mikaela, the two kids the Autobots protect, and who become caught up in the action when Sam buys a secondhand Chevy Camaro, which turns out to be the Autobot Bumblebee in disguise. (In a nod to the original cartoons, Sam skips past a Volkswagen Beetle – Bumblebee’s original form – when picking out the car.)

Get the Creative Bloq Newsletter

Daily design news, reviews, how-tos and more, as picked by the editors.

All told, ILM created around 450 shots for the film, with Digital Domain supplying another 95, including a transforming ‘Nokiabot’, a digital Mountain Dew machine and an Xbox, and contributed to the flashback and desert sequences.

Interested in animation but not sure where to begin? Check out our latest guide on how to get started in animation.

Digital transformations

However, this is very much Industrial Light & Magic’s show. ILM built and transformed all the hero robots, and built CG cars and military vehicles for the transformations.

The Autobots include Ratchet, Jazz, Bumblebee – who appears as both a 1974 and 2007 Camaro – Ironhide, and Optimus Prime. The Decepticons are Bonecrusher, Starscream, Megatron, Brawl, Barricade, Blackout, Soundbyte and Scorponok. Although a real ‘puppet’ of Bumblebee appears standing fairly still in some close-ups, all the running, jumping, fighting and transforming robots are digital.

Before production began, pre-viz artists worked with Bay to develop the fighting sequences and at ILM, animation supervisor Scott Benza worked with the director to develop the robots’ characteristics. In part, this simply involved archive research. But Benza also asked Bay to pick reference characters from movies to help establish each robot’s personality, especially the Autobots.

For example, “[Bay] picked Michael J Fox in Back to the Future as Bumblebee,” Benza says, “and Liam Neeson as Optimus Prime, the leader, who is soft-spoken but has a big presence. One of the first things I was surprised to see is that Optimus Prime has a completely articulating face and a speaking role. In the cartoon series, he had a battle mask that he spoke through, but Michael felt it was important for this character to connect with Sam and with the audience. To care about him and have him deliver an emotional performance, we needed to see his entire face.”

To create facial expressions, the modelling team, led by Dave Fogler, created sliding pieces for the cheeks and jaws, multi-segmented parts for the lips, and a turbine system for the eyes that turned to simulate pupils dilating. Optimus Prime had around 200 facial parts, and the animators could move each one.

The Transformers’ physical performances were even harder to nail than their facial expressions. “We had to find a balance between selling the weight of these heavy characters and athleticism,” says Benza. “Michael never wanted to see these guys as lumbering robots. He wanted them to be agile, not limited by their weight. It was always a problem. In animation, you need to slow movement to get [the convincing impression of] weight.”

Making progress but coding issues getting you down? Find out how to debug web animations.

Athletic martial arts move

Working from Bay’s animatics, Benza motion-captured fight scenes and used those along with footage of a variety of stunts as reference to create some shots of robots fighting. The results were promising, but Bay wanted more of a martial arts feel.

“He wanted the action to be fast, so he shot reference of stunt guys doing the spins, kicks and the martial arts actions he wanted,” says Paul Kavanagh, one of five animation leads on the show. “We got that footage and knew exactly what he required. But the action Michael wanted was performed by a 160-pound martial arts guy, and we were animating 6,000-pound robots!”

To bring the animation back into the realms of plausibility, the animators added extra frames to the reference footage of the stunt actors to slow their movements. “We could animate one-to-one to the reference, then go into the animation curve and stretch it out until it looked right to get a little more weight,” says Kavanagh.

On other occasions, the team kept the same frame rate, but added an extra action in the middle of a shot.

The animators also discovered that the closer the robots were to the camera, the faster the movements they could get away with. When their entire bodies were visible, the robot had to slow down. For emphasis, the animators even moved the robots from real time to slow motion within a shot.

“Michael had an amazing eye,” says Kavanagh. “He was always pushing us to get more and more action into each shot; to be more and more creative. We animated things over and over again until he’d say, ‘That’s how I saw it.’ I can’t think of any shots he didn’t turn up to 11 on the cool factor scale. We were psyched. We knew we were doing something special.”

Fitting in

When the modellers were building the robots and the vehicles, they did so without regard to the transformation. The CG vehicles had to match real vehicles and the robots had to match the approved concept art. “There’s not a lot of logic in how the parts function in the robots,” says Fogler. “Trying to reconcile the robot artwork to the car was pretty much impossible because the robots were so abstract in their shapes. We left it to the animators to work out the transformations. It was a leap of faith, but it worked.”

As a result, the animators worked closely with TDs to do the transformations, each one hand-animated from scratch for the camera view. Kavanagh collaborated with character TD Keiji Yamaguchi on one of the first transformations, where Barricade changed from his robot form into a police cruiser.

‘We had only the model of the car and the model of the robot,” says Kavanagh. “We didn’t have an in-between model. But it turned out not to be as complicated as we thought it would be.”

To make it possible for the animators and TDs to control creatures made from thousands of parts, ILM developed a dynamic rig. “We could select any piece of hi-res geometry or any group of pieces, create an animation controller, and choose where to put the pivots,” says Kelly.

When he animated Bonecrusher’s face smashing to pieces, he did so by selecting various parts and creating transformation controls. “We could connect parts from anywhere on the body and give them a unified pivot point,” he says. “We could move anything on these guys anywhere at any time. It was the most liberating experience.”

To create the transformations, the animators would start by animating the Transformers in one of their extreme forms: usually the robot, but sometimes the vehicle. Next, they’d fold the robot into the vehicle, doing whatever they needed to do to get it to fit. “Sometimes we had to break legs or shoulders and push arms through the chest to get the robot in the car,” says Kavanagh.

The last stage of the whole process was to animate the transformed robot standing up and moving toward the camera.

“Say you have Optimus Prime moving down the highway in his truck form and he needs to transform,” says Kelly. “We’d animate the truck as it slams on its brakes and starts skidding, and animate the robot all folded up in a position similar to the truck, and then animate the robot standing up and running away.” Once the animators received a sign-off on the animation, they then gave the pieces to Yamaguchi, or another creature TD.

Transformation super-ninja

All of the TDs’ work took place during the seconds when the robot is getting up out of the hunched position. “Keiji was the transformation super-ninja,” says Kelly. “The stuff he did was crazily complex and really intense. He used our timing and motion, but he’s the one who cut the robot into pieces and figured out how to get the pieces into the pose.”

Although he had animatics to start from, he always drew the transformation before he began animating. “The rhythm was very important for the transformations,” he says. “Also the silhouette. I wanted something very stylish, like Japanese animation or Hong Kong fighting. I also thought of gymnastics, when the gymnasts flip in the air and come down perfectly on the balance bar.”

To ease the process, Yamaguchi looked for familiar, recognisable parts in the designs – a window in Optimus Prime’s chest, for example – and moved them from the truck to the robot. He hid the small parts in the back. “I’d sketch each moving part and arrange them like orchestration for music,” he says. Once he had animated the main ‘performance’, he might use procedural animation for some of the hoses and other dangling parts, but this was a trick he used sparingly. “Simulation doesn’t have a rhythm,” he says.

“This was an action movie. It needed to be strong and vigorous.”

All in all, Yamaguchi’s longest transformation was 300 frames; the fastest was of Megatron transforming into a jet. He also transformed Bonecrusher from an army truck, Starscream from a fighter jet in flight, Optimus Prime, Jazz and Blackout.

Kavanagh also animated transformations, including Bumblebee transforming from a 74 Camaro, Blackout transforming from a helicopter, and the first Barricade transformation. “At first, the TDs had to put controllers on the geometry, but once we started using the dynamic rigging tools, the workflow got easier,” he says.

The animators also used the dynamic rigs to add secondary motion, to fix intersections which had occurred between the thousands of parts, and to move pieces that blocked the camera. “It was a key to getting this movie to work,” says Kavanagh.

During the past few years, like many other digital animation studios, ILM has been perfecting its character and creature tools; hard-surface models, on the other hand, have received much less attention. “The hard-surface shows were seen as being not as difficult as creature shows, with their issues of skin and hair, but Transformers proved to be extremely challenging,” says Russell Earl, associate visual effects supervisor. The pain was partly self-inflicted, however. “One of the early shots we finished was of the helicopter transforming into a robot. We saw that and said, ‘We have to do more of this.’ I don’t want to say we made it difficult for ourselves – but we did set the bar high early on.”

As a result, ILM had to solve problems ranging from rigging characters with thousands of parts, to lighting shots with thousands of reflecting surfaces, to managing the level of detail sufficiently to make rendering the shots feasible. “We’ve never done a hard-body show at this level before,” says Farrar.

Fact file

- Lead VFX Studio: Industrial Light & Magic

- Estimated budget: $150 million

- Project duration: One year

- Team size: Peaked at 350

- Software used: Maya, Zeno, mental ray, RenderMan, Photoshop, Shake, in-house tools

With Transformers, Industrial Light & Magic pushed the limits of what can be achieved in computer animation, but find out how they took the second film to another level in our second Transformers article: The making of Transformers: Revenge of the Fallen.

Now check out ILM's step-by-step guide showing how rigs, match move and live-action footage were used to make the Transformers come alive.

IN FOCUS: How rigs, match move and live-action footage were used to make the Transformers come alive

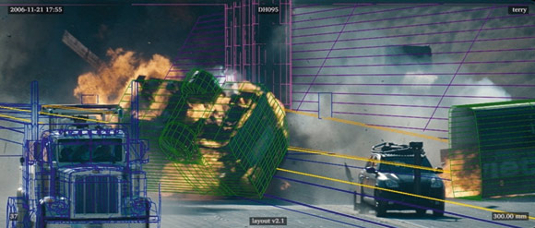

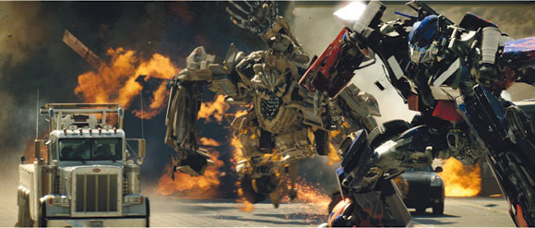

1) This is the original live-action footage. Director Michael Bay shot much of the destruction in Transformers on camera, including the exploding vehicles in this shot. During this sequence, the Decepticon Bonecrusher has just flipped the flaming car and is confronting the Autobot leader Optimus Prime.

2) In order to be able to place digital robots into a previously filmed shot, ILM’s camera tracking and match-moving department determine exactly where the real vehicles are in 3D space and how the live-action camera moved through the sequence. None of these vehicles transform in this shot.

3) Modellers created Bonecrusher using 2,980 pieces of geometry and 855,483 polygons. The total length of these pieces, if lined up side by side, would be 2,252 feet and their total volume would be 4,430 cubic feet. Bonecrusher can transform into a Buffalo minesweeping vehicle, although he doesn’t in this shot.

4) Animators created the performances for Bonecrusher in the background and Optimus Prime in the foreground. To move Bonecrusher’s rigid metal parts, animators used 7,824 rigging nodes; for Optimus Prime, they had 27,744 nodes. A dynamic rig allowed animators to group any of the pieces and assign pivot points to the group.

5) The animated robots are then placed into the plate. Animators manipulated the robot pieces to create the most interesting shots from the camera’s viewpoint. For slow-motion shots, animators used a retiming curve that allowed them to retime the live-action plate and the camera match move and then attach the characters to the curve.

6) To create the final shot, compositors integrated the fully rendered and lit robots into the plate. ILM relied on RenderMan and mental ray for rendering using environment maps created from photographs taken on site during filming, and raytracing to create reflections on the hard-surface models.

Now check out some fun facts about Megatron and Optimus Prime, and read some awesome Transformer statistics supplied by ILM, by clicking Next

Thank you for reading 5 articles this month* Join now for unlimited access

Enjoy your first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

*Read 5 free articles per month without a subscription

Join now for unlimited access

Try first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

The Creative Bloq team is made up of a group of design fans, and has changed and evolved since Creative Bloq began back in 2012. The current website team consists of eight full-time members of staff: Editor Georgia Coggan, Deputy Editor Rosie Hilder, Ecommerce Editor Beren Neale, Senior News Editor Daniel Piper, Editor, Digital Art and 3D Ian Dean, Tech Reviews Editor Erlingur Einarsson, Ecommerce Writer Beth Nicholls and Staff Writer Natalie Fear, as well as a roster of freelancers from around the world. The ImagineFX magazine team also pitch in, ensuring that content from leading digital art publication ImagineFX is represented on Creative Bloq.