Create powerful artistic compositions: 21 pro tips

Create stronger artistic compositions using techniques ranging from the Golden Ratio to implied lines.

Strong artistic compositions are vital to the success of a piece of art. The composition of a piece is what captures a viewer's eye and holds their attention once they take a closer look.

Artistic composition can totally change the mood of a piece of art, changing it from vibrant energy to solemn contemplation. But how does this happen? Why do some seemingly beautifully rendered pictures fail to hold up whereas others captivate viewers?

Many rules dictate what makes a good composition, for example the Golden Ratio, the Golden Spiral and the Rule of Thirds. However, it is crucial we don't approach these theories as unbreakable rules but see them as suggestions, or optional templates.

We'll discuss some of these techniques throughout this article, explain why they are successful and how you can use that knowledge to make a better image.

To begin, all you really need to know is this: a good composition is nothing more than a pleasing arrangement of shapes, colours and tones. That's simple enough really. Chances are, most of you can make a good composition with your eyes closed.

Click on the icon at the top-right of the image to enlarge it.

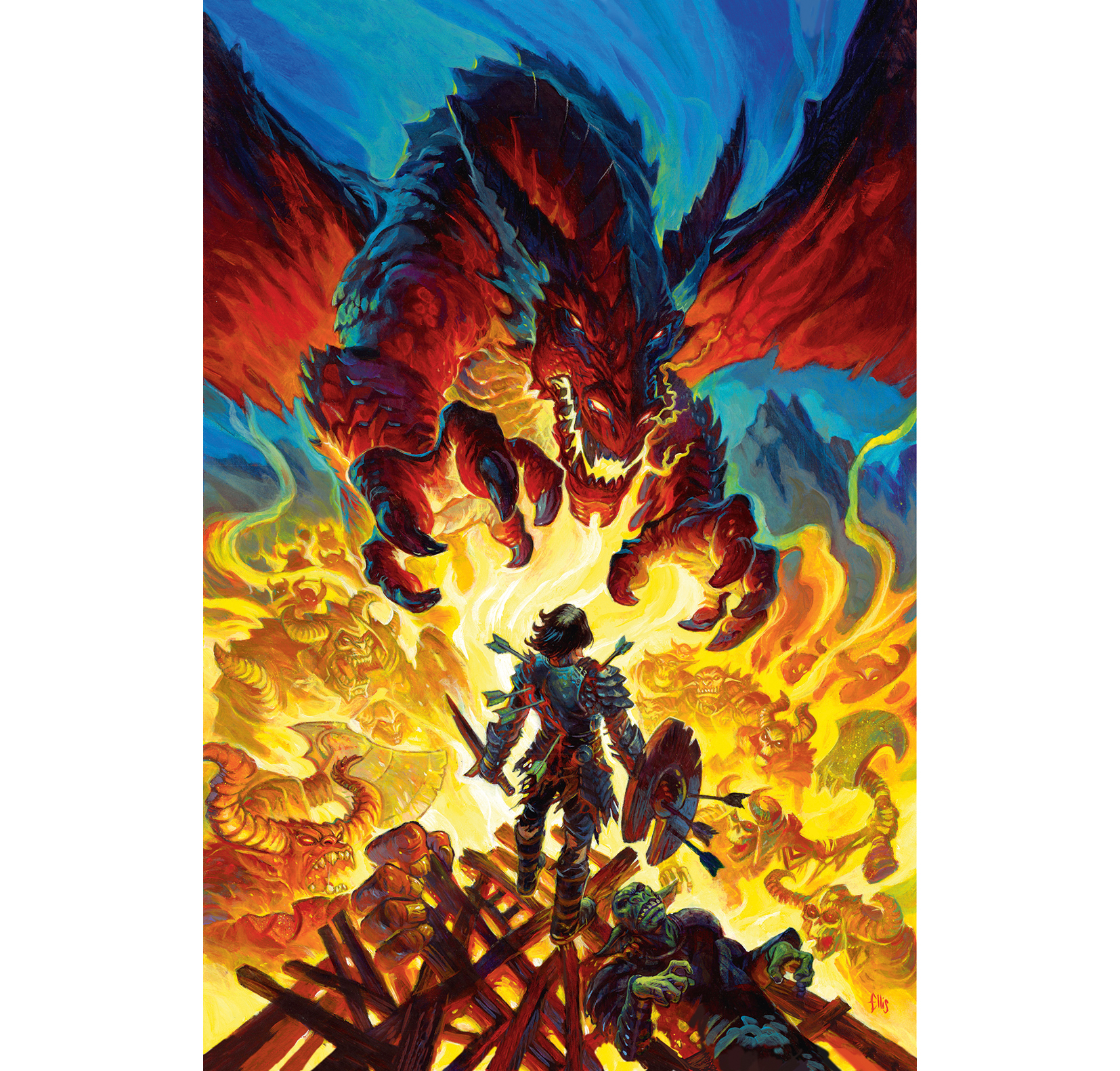

01. Tell the story

Whether it’s a professional brief or notes for a personal piece, the first step is to think about the story. Which elements are crucial to telling the story, which are secondary, and which add tertiary support? This is how you figure out the hierarchy of elements in your piece. Here, the confrontation between the warrior and the dragon should be paramount, but the secondary elements, such as the wrecked wooden platform, need to support the central narrative of the piece.

02. Create relationships

As simple as this image is, it already has a sense of motion, and depth. How?

Through relationships. Causing a disparity between the shapes has given the viewer a means by which they can compare those shapes. "This one is bigger, that one is lighter." The grey square appears to be moving and receding only when compared to the black square.

The process of comparing these shapes requires that the viewer moves their eyes repeatedly around the canvas, and therein lies the true goal of a great composition: controlling that eye movement.

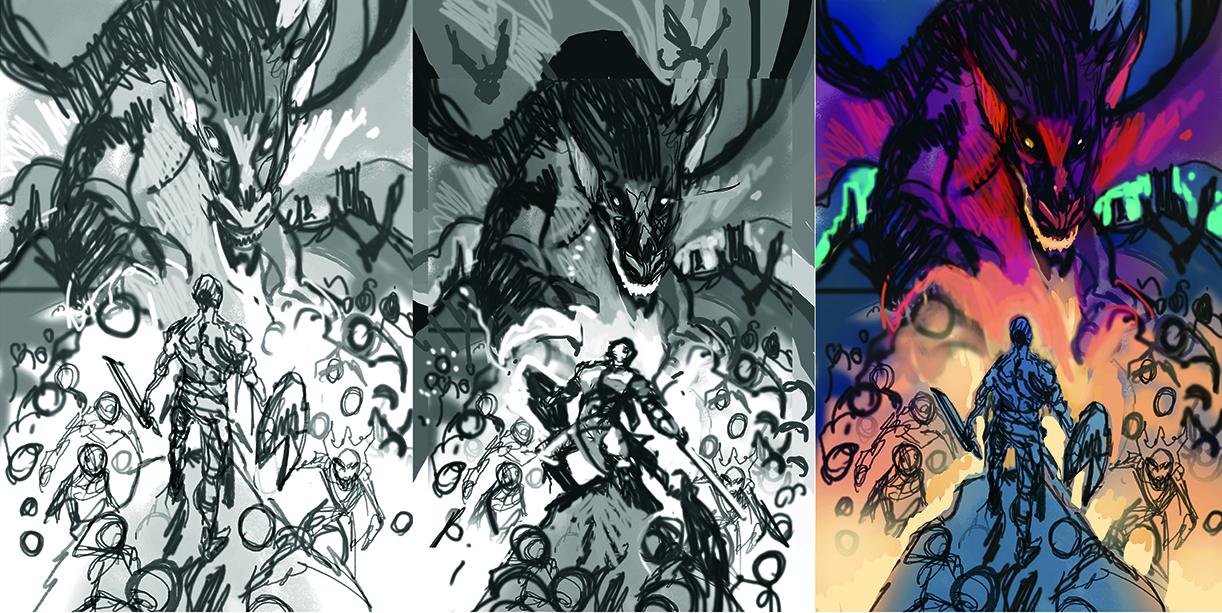

03. Think in thumbnails

Start with thumbnails that are the same size ratio and orientation as your final image. If the thumbnails are at the wrong dimensions, you'll end up with all your balances off-kilter, and have to rework your design. During this early stage it's important to solve many of the design problems before even thinking about the final image. The delicate balancing of elements can lead to a strong image, while a slight misplacement can change or alter the impact of the image you’re creating.

04. Know shape matters

Plan for the outside shape of the image. This is a personal piece, therefore the size was able to be set. Commissioned pieces don't allow for this luxury and the artist has to react to the dimensions provided. Everything in your image needs to relate to the border dimensions. That’s why the canvas size is crucial. It creates the framing device for the image – the shape that the viewer will be looking through. Once the outer dimensions are established, the design can be approached from a few different directions.

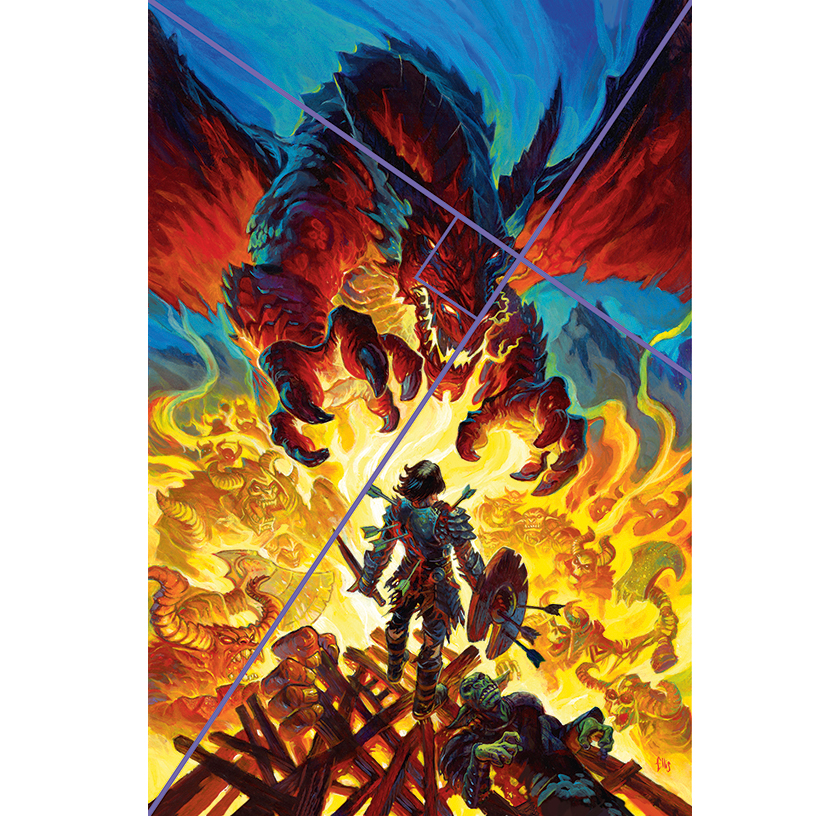

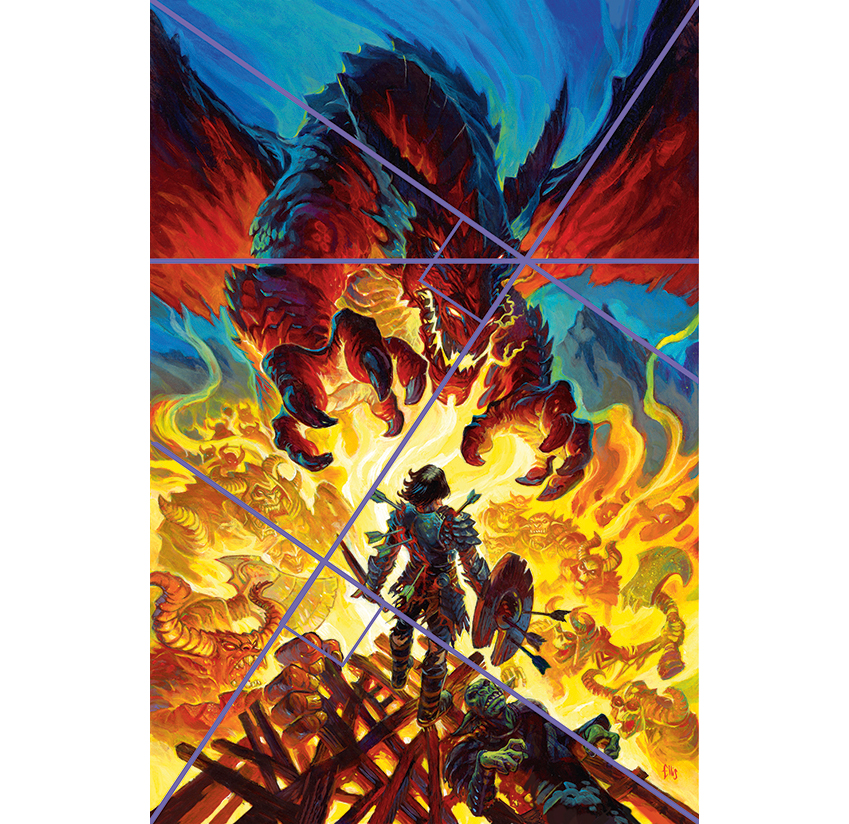

05. Develop dynamic symmetry

Great compositions use geometry. Here’s an example of how dynamic symmetry helps to take this piece to a deeper compositional level…

a) Line art

Using the initial sketch, draw a line from the top right corner to the lower left corner. Then, from the top left corner draw a line at right angles to the first line. This is the primary point of interest, and where you'll paint the dragon’s eye.

b) Identify edges

Draw a line straight across at the primary point to establish the dragon’s eyeline. Then place a line from the bottom right corner at a right angle to the original line. These help to establish important elements like the edge of the platform, the orc’s side and the dragon’s wing.

c) Check placement of elements

Next, repeat these steps, starting at the top-left corner. Using these guides, locate the edge of the platform, the left wing and the warrior’s hands. This enables you to see that the warrior is right in the middle of the diamond shape. The dragon’s head, shifted right, is now in the upper diamond

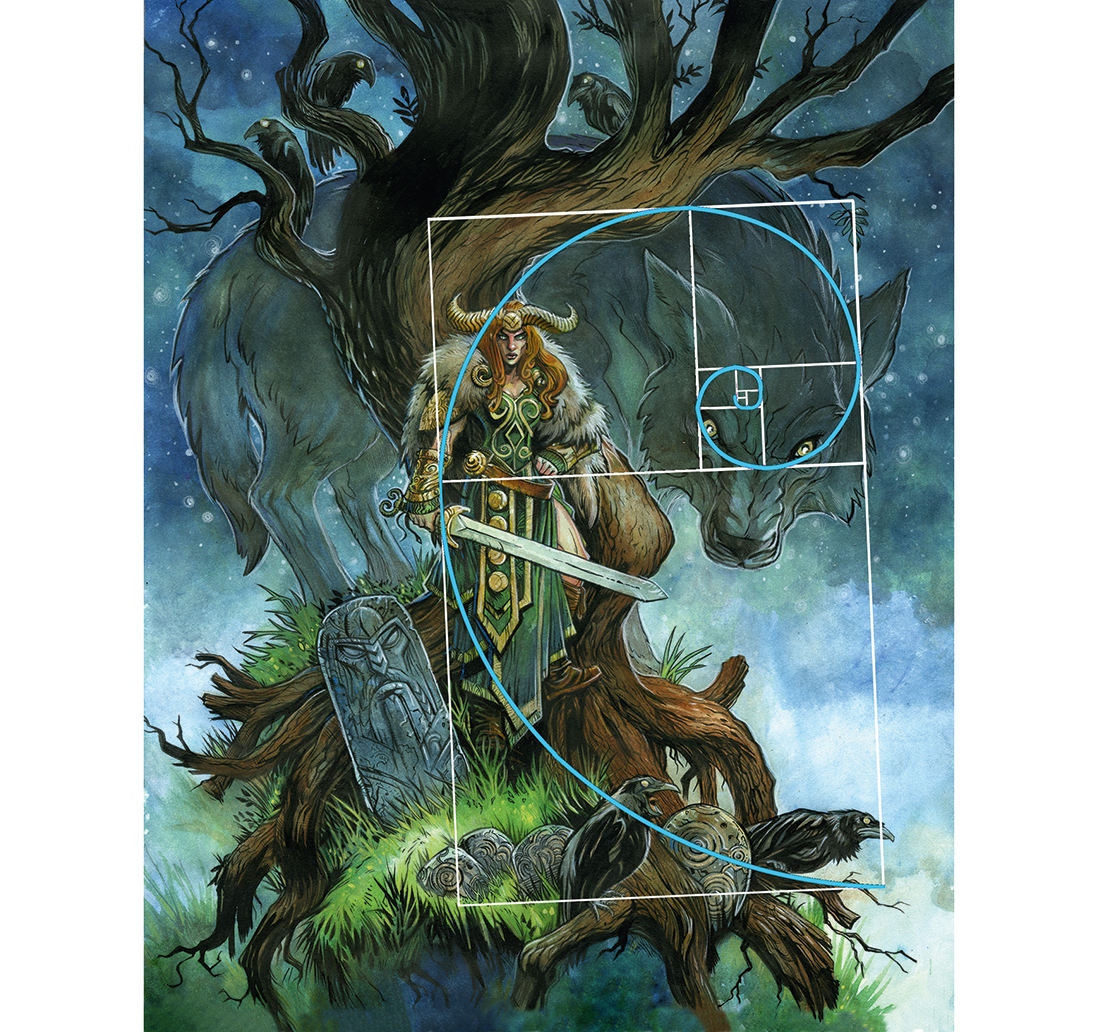

06. Apply the Golden Ratio

Sometimes, dynamic symmetry doesn't feel right for a piece and this is where The Golden Ratio is most useful. This Greek mathematical equation expresses itself as a spiral. Many of the most famous pieces of art use this ratio to decide on the placement of elements and as a natural way to lead the eye across an image. It’s so embedded in our natural world and our humanity that we often use the ratio without realising it.

They believed that all things, both tangible and intangible, have a perfect state of being that define them. They also felt that one should always strive toward achieving this ideal state, be it in mathematics, one's physique, politics or aesthetics.

Greek mathematicians, after repeatedly seeing similar proportions in nature and geometry, developed a mathematical formula for what they considered an ideal rectangle: a rectangle whose sides are at a 1:1.62 ratio.

They felt that all objects whose proportions exhibited this were more pleasing, whether a building, a face or a work of art. To this day, books and even credit cards still conform to this ideal.

In the case of the image above, the spiral has been used to create a harmony for the elements of interest, such as the wolf’s eyes, Morrigan, the tree and the ravens.

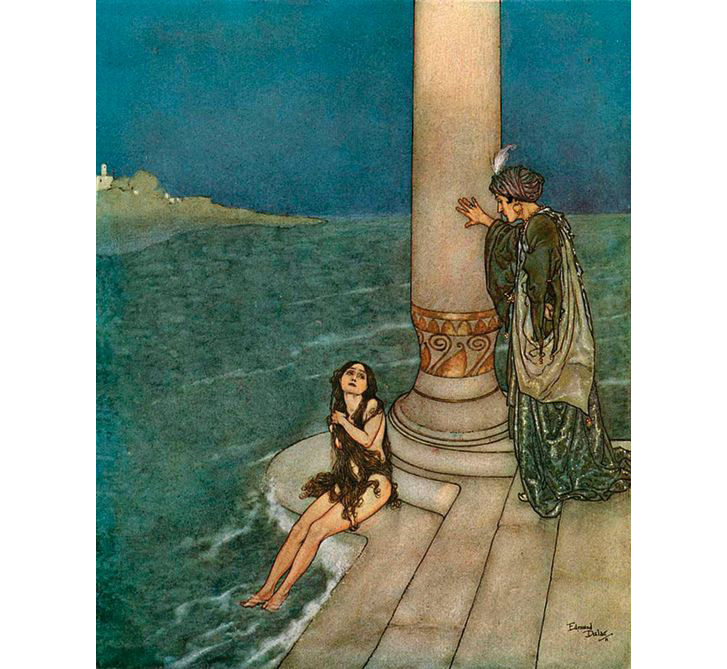

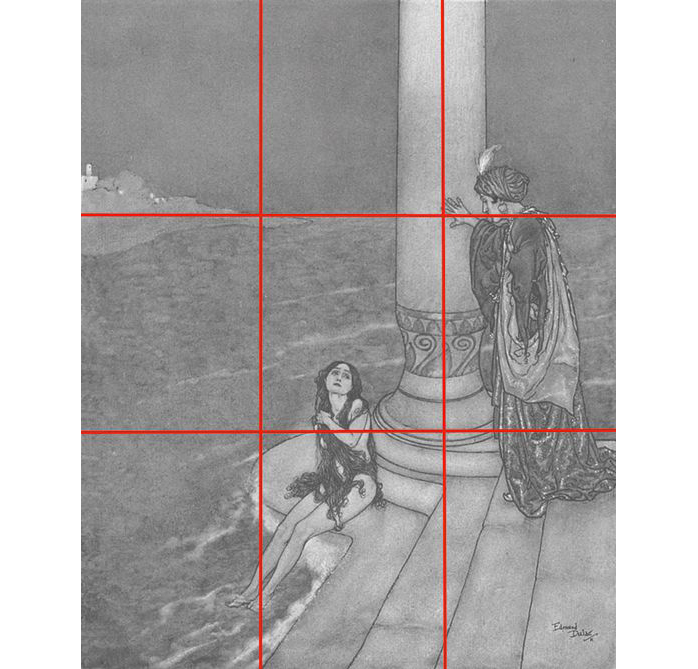

07. Channel The Rule of Thirds

This states that if you divide any composition into thirds, vertically and horizontally, then place the key elements of your image either along these lines or at the junctions of them. You'll achieve a more pleasing arrangement. But does it work?

Let's look at Edmund Dulac's painting, The Little Mermaid: The Prince Asked Who She Was (above). Dulac was great at using empty space to his advantage, partly because he tended to abide by the Rule of Thirds.

Here Dulac has placed the column and the horizon line perfectly along a line of thirds. But what if he didn't?

With the column and horizon line in the centre of the image, the result is less successful. The column dominates the image, stealing focus away from the figures.

The viewer's eye is now glued to this strong shape that bisects the canvas, instead of wandering around the image like it originally did.

08. Learn how the rules work

The Rule of Thirds works because it demands that the artist makes one element more dominant than another. This dominance creates an imbalance, and an imbalance of any sort will always attract the viewer's eye.

Bisecting an image perfectly in half creates the least amount of interest, because everything is equally balanced.

Making one area of your composition more dominant creates tension, and therefore adds interest. It also makes your eyes move around the canvas more to compare all of these relationships.

The fact that the composition is divided into precise thirds is really of minimal significance. You could divide a composition in fourths, fifths or even tenths. So long as there's some sort of imbalance, the composition will exhibit tension. As you'll soon see, this concept of imbalance applies to many aspects of composition, including value and colour.

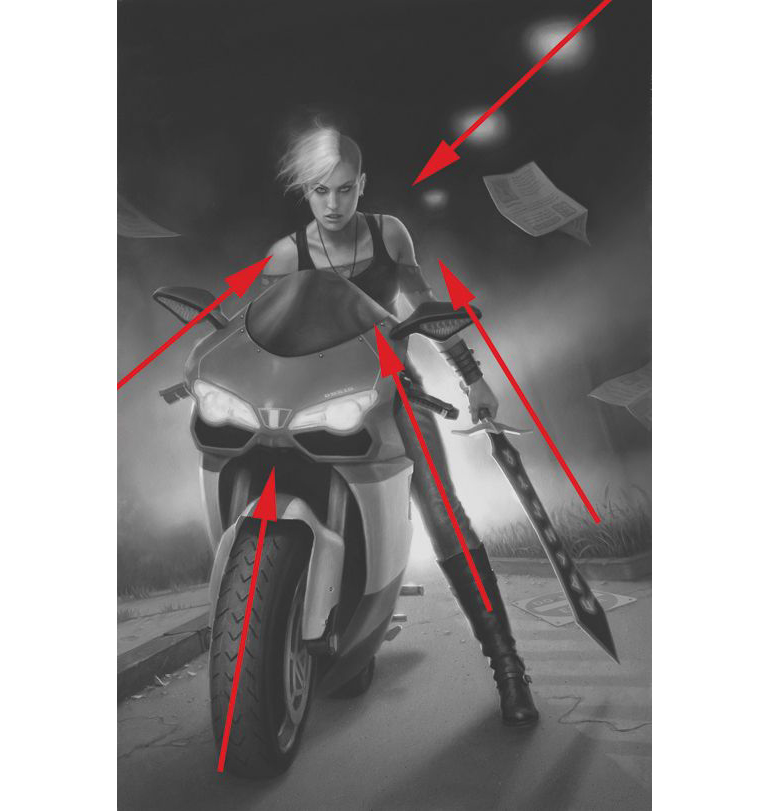

09. Use implied lines

These are probably the most important aspect of a composition, because you notice them first. When painting realistically, there's no actual line around a subject.

The illusion of a contour is a result of different values and colours contrasting. But even the impression of a line is strong, and our eyes will go to it and follow its length until it ends, or until it meets another line, which we'll follow again. A great composition makes strong use of this natural attraction to lines.

Sweeping action or movements across a piece will draw the eye from one side of a composition to the other. Using strong, direct action lines built into elements of the picture can move the eye to the point you want. In non-action pieces or in the calmer areas of action scenes, use elements such as flowing cloth, curling smoke or even directional brush strokes in the sky – all subtle trails that the eye can follow to the image’s focal point. Here, the waves, the tentacles and the shape of the sail direct the eye.

10. Reinforce those focal points

As well as using implied lines to draw the eye all around a composition, you can use the same method to make someone look immediately at your chosen focal point.

In fact, you can do it repeatedly, from multiple directions. This is particularly useful when your image is a portrait or a pin-up, and the character's face is the most important element.

To bring more attention to a particular character, try to make surrounding objects, such as arms, swords and buildings, point to your subject. You can also use implied lines to frame the subject's face, locking the viewer's eyes in place.

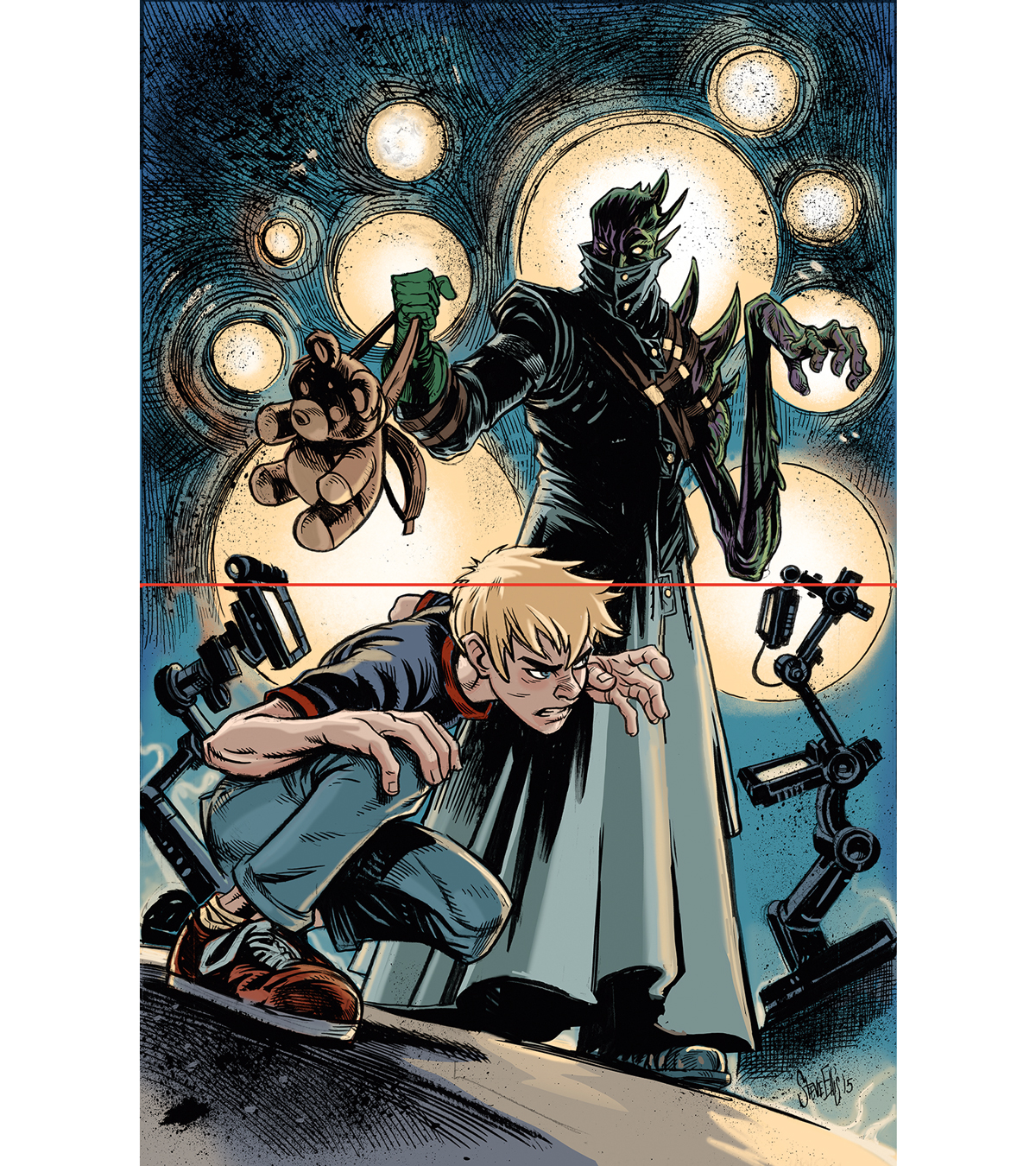

11. Create drama via a point of view

For an emotionally effective piece such as this, the viewer should place themselves in the head of the warrior. Our hero – and thus the viewer – should feel overwhelmed and outmatched, but still willing to fight. To achieve this, the villain has been placed above the midpoint of the picture. The angle has been canted a bit to throw the viewer off-kilter as well. That way, the villain is literally looming over us as well as the boy.

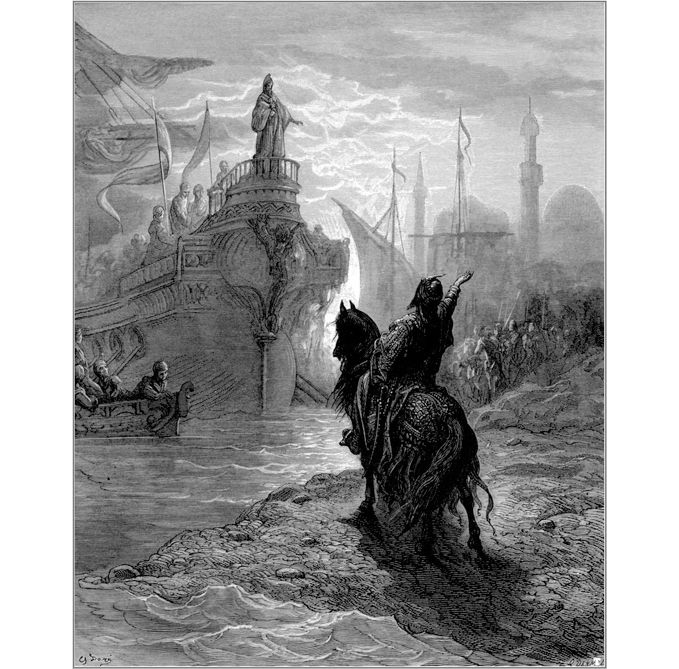

12. See threes everywhere

The Rule of Thirds seems to work its way into most aspects of picture making, and value is no exception. When constructing compositions, think in general arrangements of foreground, middle-ground and background.

To heighten the relationship between these three depths, try to restrict each to a range of value, favouring black, white or grey. For instance, you can let the background predominately be white tones, the middle-ground predominantly greys and the foreground predominantly black tones.

Of course, any arrangement of these three values will work. By restricting your values in these areas you reinforce your image's sense of depth and make the silhouettes very easy to read – and that legibility is important.

Muddy values hurt the viewer's ability to discern shapes, especially at a small scale. That's why you'll see this technique used so often in trading card art. When your image is just a few inches tall, high-contrast compositions work especially well.

Triptych value schemes like this are readily apparent in the works of the Old Masters, particularly in the engravings of Gustave Doré.

His paintings all show different arrangements of black, white and grey to emphasise the difference between foreground, middle-ground and background.

13. Harness the power of triangles

Compositions are often based around strong, simple shapes. Here, the heroes in this piece need to have an individual moment to themselves, but also to fit together as a team. Because a triangle is a strong shape the team has been composed so that its various elements led the eye to the orc paladin’s head (the green triangle). And because the background is also arranged as a downwards-pointing triangle (the blue triangle), it creates a diamond shape where the heads of the main figures are approximately placed. All of this is meant to pull the reader towards the expressions on the characters’ faces.

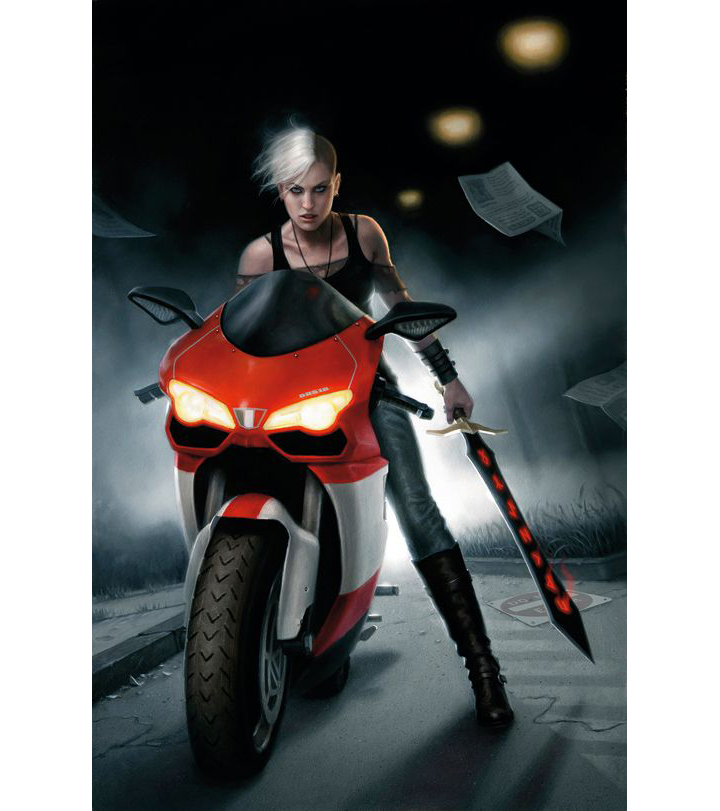

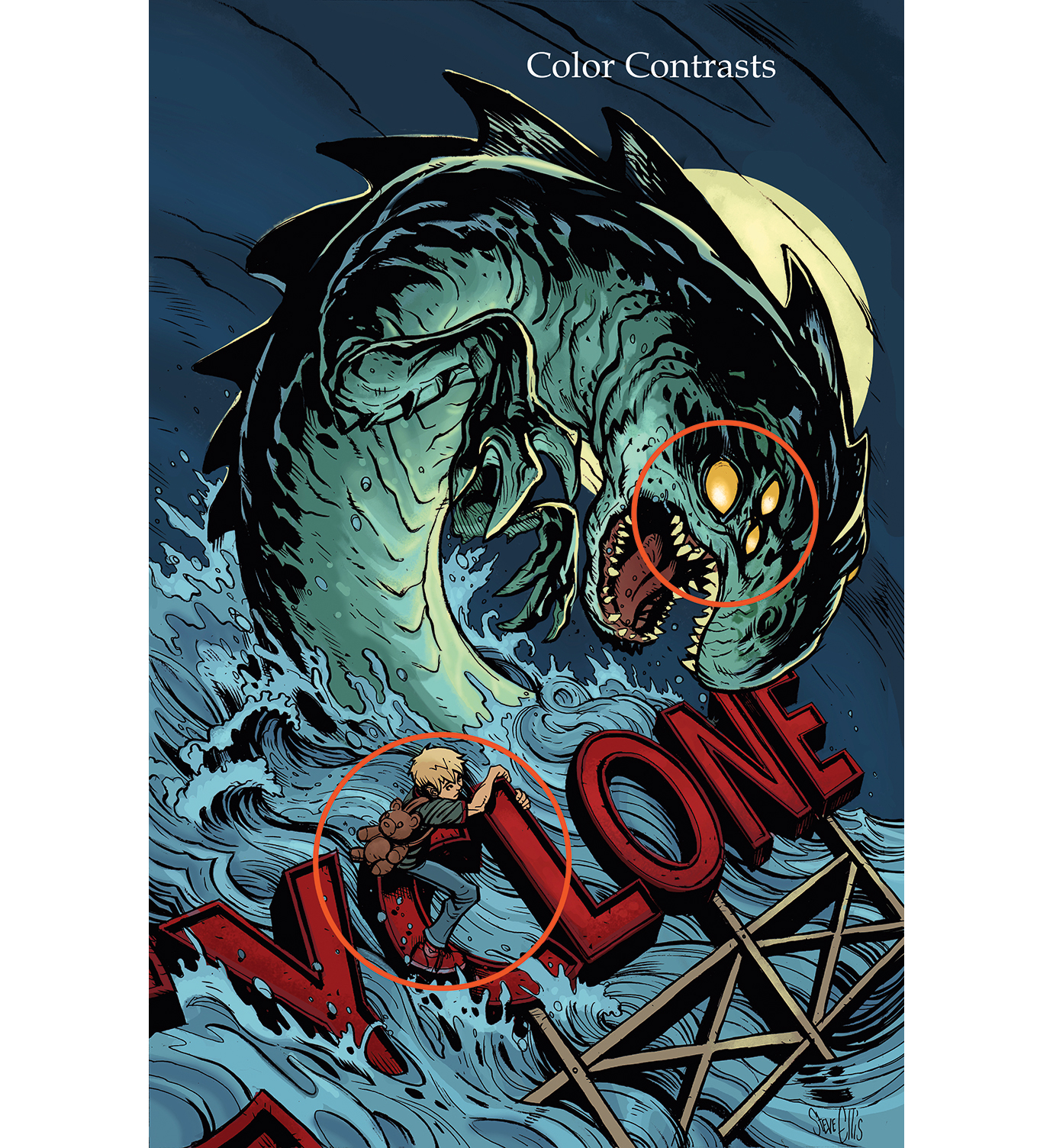

14. Be clever with colour

Colour is an amazing tool for composition. In a piece where I want something to hit hard I’ll use a lot of contrasting value of colour as well as complementary colour. A bright warm colour in the middle of a field of cool can really pop out of a scene and draw the viewer’s eye. Here, the word ‘Cyclone’ is a dark red so that contrasts against the blue of the water, while the eyes of the serpent are bright yellow against the dark turquoise of the sky. The boy has been highlighted with yellow and a lighter skin tone, to bring him forward against the sign and the water.

Black and white are inherently powerful tones. If you use them sparingly, and right next to each other, you can draw the viewer's attention to a particular spot with ease.

When painting, try reserving the purest whites and blacks for your focal point. For instance, if your main character has very pale skin, try placing something extremely dark on them, such as black hair or black clothes.

This is one of the easiest and most successful ways of making your subject pop. In the above painting, Blood Divided, this has the effect of sitting the heroine apart from the background.

15. Consider your angle

Imbalance can create a more exciting flow to your composition, but it can also add drama. The next time your painting isn't exciting enough, try tipping the camera angle.

Even the slightest tip to the horizon line can turn a mundane scene into a cool action shot. Experiment with the psychological impressions that different camera angles create.

Straight, this painting lacks real excitement. The bricks, rain and hair all create simple vertical lines, and don't do much to enhance the drama of the piece. Tipping the image gives it a whole new feel.

Suddenly it appears like the woman is being thrust against the wall. There's also more of a sense of weight to their poses

16. Assess the silhouette

When planning a painting, think about how the image will look as a silhouette. Compositionally, the silhouette is the outer edge of the main forms of the foreground objects or figures. If it works in black and white as a composition then there’s a good chance that the composition should work fine in colour, if you don’t mess around with the colour values too much. Also, make sure that the silhouette is interesting and background elements don’t compete with it.

17. Vary symmetry or asymmetry

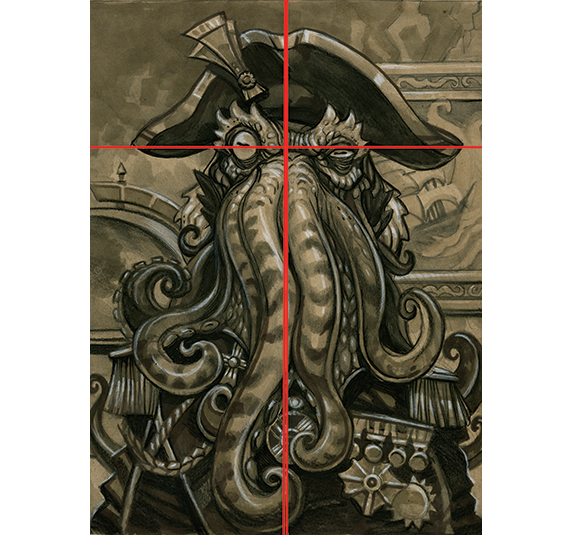

Symmetry is great at telegraphing order and calm, but it can be pretty unexciting. Sometimes, as with this portrait, think about bilateral symmetry, but vary the elements a bit to keep the piece feeling active: the expression in the eyes, and the positioning, shape and size of the different tentacles, for example. Also balance the background elements without repeating them, so that they retain a sense of energy.

18. Play it big and bold

Sometimes it pays to be blatant with your design elements. Just look at any Norman Rockwell Saturday Evening Post cover. I’ll often use a giant circle on one of my points of interest in a piece, creating a halo around the main character or action. This draws the viewer’s attention to anything that breaks out of that circle. Taking this approach also works with other simple shapes, such as a diamond or a triangle.

19. Think ahead to the final product

It’s important to think about the final home of the art. Is it a game card or book cover, or will it hang on a wall? Gallery art has different compositional needs than a card image or a 6x9-inch comic book cover. While a strong composition will work on many levels, the intensity of detail needed for a larger reproduction may not be necessary for a tiny card. Simple shape compositions can be strongest for small pieces, but might seem too simple when enlarged.

20. Stay loose

While such advice can help to create strong images, if they ever become restrictive, throw out the rules and do some unstructured sketching. Use bigger, looser, bolder strokes and shapes and then go back to these tips. In the end you never want to lose the spontaneity in the image, otherwise it loses its fun. If making the art isn’t fun for the artist, it won’t be fun for the viewer.

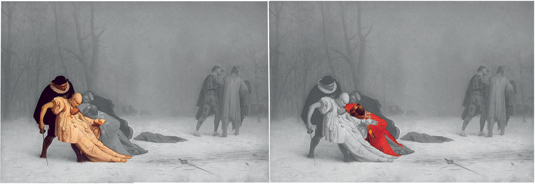

21. Put it all together

A good composition is one where the artist controls the movement of the viewer's eye to a beneficial result.

We can do this by a number of means, such as reinforcing the focal point with the Rule of Thirds, implied lines, contrast of value and selective colour saturation.

Putting all of these tools into action in a single piece, Jean-Léon Gérôme's Duel After a Masquerade Ball is the perfect example of using all compositional devices to your advantage.

This content originally appeared in ImagineFX; subscribe here.

Read more:

Thank you for reading 5 articles this month* Join now for unlimited access

Enjoy your first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

*Read 5 free articles per month without a subscription

Join now for unlimited access

Try first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

Get the Creative Bloq Newsletter

Daily design news, reviews, how-tos and more, as picked by the editors.